Entry Category: Civil Rights and Social Change

Hogan, Richard Nathaniel

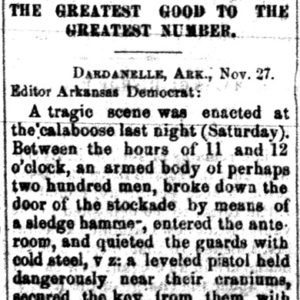

Jim Holland Lynching Article

Jim Holland Lynching Article

Hollingsworth, Perlesta Arthur “Les”

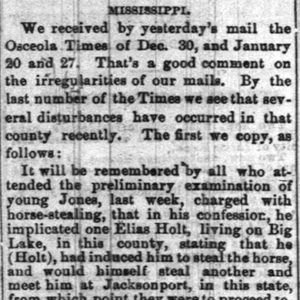

Elias Holt Lynching Article

Elias Holt Lynching Article

Homelessness

Hoover, Theressa

Hopkins v. Jegley

Horace Mann High School

Horace Mann High School

Hot Spring County Lynching

Hot Spring County Lynching

Hot Springs Schools, Desegregation of

Howard County Race Riot of 1883

aka: Hempstead County Race Riot of 1883

Howard County Reported Lynching of 1894

Howard Federal Building

Howard Federal Building

Howard, George, Jr.

George Howard Jr.

George Howard Jr.

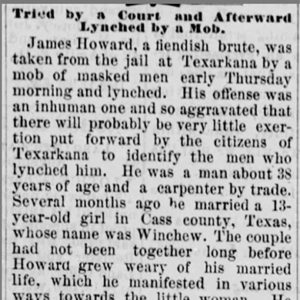

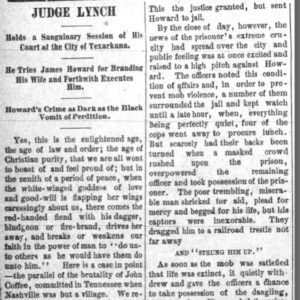

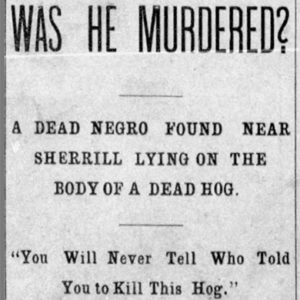

James Howard Lynching Article

James Howard Lynching Article

James Howard Lynching Article

James Howard Lynching Article

Howard, Jesse (Lynching of)

Hoxie Schools, Desegregation of

Huckaby, Elizabeth Paisley

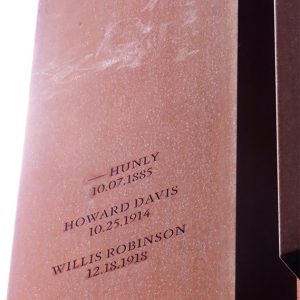

Hunley, Dan (Lynching of)

Hunt, Silas Herbert

Hunter, Buck (Lynching of)

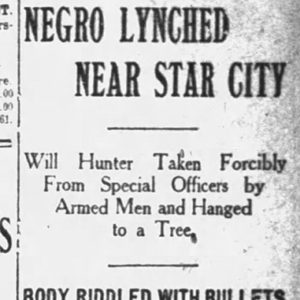

Hunter, William (Lynching of)

William Hunter Lynching Article

William Hunter Lynching Article

Hutton, Bobby James

Hyman, Ralph Allen

Hazel Hynson

Hazel Hynson

Iggers, Georg

Iggers, Wilma Abeles

Indian Removal

Intrastate Commerce Improvement Act

aka: Act 137 of 2015

Ivey, Helen Booker

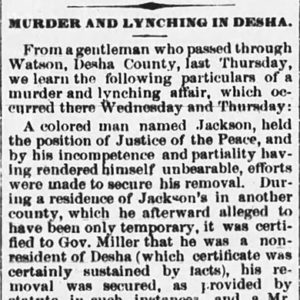

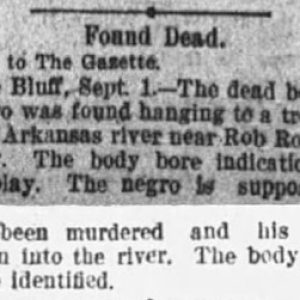

Jackson County Lynching

Jackson County Lynching

Jackson, Gertrude Newsome

Jackson, Henry (Lynching of)

Henry Jackson Lynching Article

Henry Jackson Lynching Article

James, Henry (Lynching of)

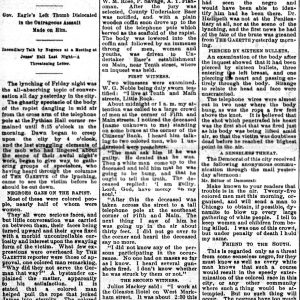

James Lynching Article

James Lynching Article

James Lynching Editorial

James Lynching Editorial

Jameson, Jordan (Lynching of)

Japanese American Relocation Camps

Jeannette, Gertrude Hadley

Gertrude Jeannette

Gertrude Jeannette

Jefferies, Oscar (Lynching of)

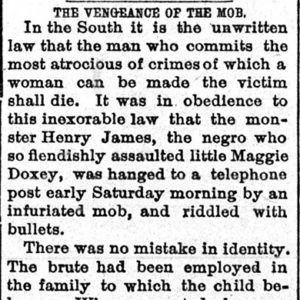

Jefferson County Lynching Article

Jefferson County Lynching Article

Jefferson County Lynching Article

Jefferson County Lynching Article