calsfoundation@cals.org

Vertac

The Vertac site in Jacksonville (Pulaski County) is one of the nation’s worst hazardous waste sites and Arkansas’s most publicized Superfund site. Cleanup of the area after its abandonment by its corporate owner took more than a decade, and the name “Vertac” soon became synonymous in Arkansas with the fear of industrial pollution, similar to how New Yorkers view Love Canal.

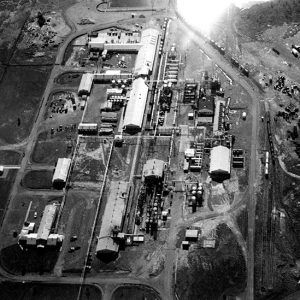

The Vertac site was originally part of the Arkansas Ordnance Plant (AOP), a World War II–era facility that manufactured various components of explosive devices, such as primers and detonators. In 1946, the federal government offered the AOP facilities for sale to private companies. The future Vertac site was purchased in 1948 by Reasor-Hill Company, which produced pesticides, as did the Hercules Powder Company, which bought the facility in 1961. Both of these companies manufactured the now-banned DDT, as well as 2,4-D (2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) and 2,4,5-T (2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid). Ten years after purchasing the facility, Hercules Powder Company began leasing the site to Transvaal, Inc., which bought the site in 1976 but filed for bankruptcy only two years later. In 1978, Vertac Chemical Corporation of Memphis, Tennessee, obtained the site.

The same year that the Vertac company began its tenure in Jacksonville, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) banned the sale of herbicide 2,4,5-T, though it continued allowing the use of the chemical on rice fields. (Agent Orange, the defoliant used widely by the U.S. military during the Vietnam War, was equal parts 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T.) A byproduct of 2,4,5-T production is dioxins—extremely toxic chemicals linked to cancer, disorders of the nervous system, miscarriages, birth defects, spina bifida, and more. The city of Times Beach, Missouri, was evacuated in the early 1980s after federal investigators found high levels of dioxin in the city’s soil and water. More notorious was the Love Canal neighborhood of Niagara Falls, New York, which was the site of a chemical dump for Hooker Chemicals and Plastics Corporation; these chemicals seeped into the surrounding area and caused an outbreak of cancers, birth defects, and other health problems. President Jimmy Carter eventually declared the Love Canal area a state of emergency, and all residents were evacuated. The publicity these disasters received—along with Kentucky’s “Valley of the Drums,” described widely as “the nation’s poster child for industrial negligence”—led in 1980 to the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), commonly known as the Superfund law. Created to deal with abandoned sites of industrial pollution, CERCLA taxed and fined companies to recover clean-up costs and established containment procedures for such intensively polluted sites.

Both Hercules and Vertac had buried an untold number of dioxin-contaminated drums at the Jacksonville site. In 1979, the EPA investigated the Vertac site and found numerous drums releasing hazardous chemicals into the environment. The Arkansas Department of Pollution Control and Ecology (ADPC&E), later the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ), forbade Vertac from continuing the manufacture of the very profitable 2,4,5-T and required the company to improve its practices of disposing of hazardous wastes. The discovery later that year of traces of dioxin in fish in a nearby creek led the EPA and the ADPC&E jointly to sue both Vertac and Hercules, and federal Judge Henry Woods ordered Vertac to prevent the spread of dioxin in the surrounding environment, most notably by constructing a wall around its waste pond. A 1979 article in Life magazine dubbed Jacksonville a “poisoned town.” After tests on June 9, 1985, the EPA warned local residents that local water wells were contaminated with dioxin. Meanwhile, still forbidden from manufacturing 2,4,5-T, Vertac began laying off employees through the next few years.

Jacksonville residents frequently received conflicting information about the level of contamination in their community. After further testing of local wells on July 11, 1985, the EPA retracted its earlier claim of dioxin contamination, citing potential laboratory errors for the initial report. Three years later, the EPA completely downgraded its assessment of dioxin’s toxicity, a decision that came under serious criticism, especially given other recently published studies on the detrimental effects of dioxin upon the immune system and its link with cancer. The EPA’s 1985 and 1988 retraction of previous dioxin claims did not help to stave off financial troubles for Vertac, however, and the company abandoned its Jacksonville site in 1987, declaring bankruptcy and leaving behind nearly 29,000 drums of chemical wastes, many already corroding; some 15,000 of these had been left outside, exposed to the elements. Sandy Davis and Bobbi Ridlehoover of the Arkansas Democrat interviewed workers and residents in the 1980s and 1990s, publishing the findings of their investigations.

The EPA declared the Vertac site a Superfund site and initiated the cleanup and containment process. The initial plan decided upon by the EPA and ADPC&E was to incinerate the waste at the Vertac site, but this met with opposition by local residents, some of whom filed a lawsuit in 1989 to prevent the incineration from taking place. Some of the first tests of this process were beset by technical problems, leading the ADPC&E to halt incineration for a while in 1991. Four separate legal actions to halt the incineration were eventually decided in the government’s favor, and by late 1994 more than 23,000 drums had been burned; the remainder was shipped to Coffeyville, Kansas, for incineration. After the incineration, the EPA proceeded to carry out clean-up on contaminated soil and destroy the remaining industrial structures.

On September 1, 1998, the city of Jacksonville marked the official end of the site’s cleanup, which cost more than $150 million. However, many residents continued to believe that not enough had been done to secure their safety. On April 23, 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court, after years of litigation, let stand a lower court ruling that held Hercules responsible for $120 million of the clean-up costs. By slipping into receivership, the Vertac company evaded any responsibility for the damages. The site is listed as safe by the EPA, but the legacy of industrial waste remains with the location and with the entire city of Jacksonville.

In 2000, the city acquired the northern section of the property, with a Superfund Redevelopment Initiative Pilot grant enabling reuse of the site. Site reuses include a recycling center, office space, storage, a fire department training facility, a driver training pad, a recycling education park, and a police firing range. Construction also began on a new police and fire training center, police department facilities, and an emergency operations center and community safe room for use during severe weather. In 2014, the EPA reported that it would begin the process of testing properties near the Vertac site, following a 2012 revision of guidelines on safe dioxin levels, but by 2022, such testing had not yet been undertaken; the testing finally began in May 2023.

For additional information:

Ault, Larry. “Ceremony to Mark End of Vertac Waste Cleanup.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 30, 2008, pp. 1B, 3B.

Clamp, Mark D. “Dealing with Dioxin: The Case of Vertac.” Pulaski County Historical Review 48 (Spring 2000): 2–8.

Langhorne, Will. “Jacksonville Soil Testing Not Begun.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 18, 2022, pp. 1A, 8A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/dec/18/a-years-long-delay-in-testing-for-a-hazardous/ (accessed December 19, 2022).

———. “Sampling of Soil around Vertac Site Finally Will Begin.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 15, 2023, pp. 1A, 8A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/may/14/contractors-scheduled-to-gather-soil-samples-from/ (accessed May 15, 2023).

Ridlehoover, Bobbi. “Agency May Renew Vertac Permit Without Testing.” Arkansas Democrat, June 29, 1983, p. 5B.

———. “Despite Grim Scene, EPA Making Progress.” Arkansas Democrat, August 9, 1987, pp. 1B, 5B.

———. “Landfill Worker Ill, Another Dead.” Arkansas Democrat, February 4, 1983, pp. 1A, 5A.

Satter, Linda. “Suit over Vertac Not Finished Yet.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 20, 2012, pp. 1B, 8B.

———. “U.S. Justices Let Vertac Tab Stand.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 24, 2007, pp. 1B, 6B.

Stone, Margaret Frances. “Small Town Superfund: History of the Vertac Superfund Site in Jacksonville, Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2024.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “On-Site Incineration at the Vertac Chemical Corporation Superfund Site, Jacksonville, Arkansas.” http://clu-in.org/download/remed/incpdf/vertac.pdf (accessed April 19, 2022).

———. Record of Decision–Vertac Superfund Site. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1996.

“Vertac Superfund Site.” Environmental Protection Agency. http://www.epa.gov/region6/6sf/pdffiles/vertac-ar.pdf (accessed April 19, 2022).

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

I was stationed at Little Rock AFB in Arkansas twice during my Air Force career, both times as a security policeman. The first time was in the mid-1970s and the second was from 1978 through 1981. We would often have our training exercises in the areas on LRAFB and at Camp Robinson located in North Little Rock. I lived at the Hill House apartments, located across the street from the Vertac plant. The ground in our backyard was orange as was the dirt in the small creek that ran adjacent to our backyard. The Vertac plant was also located adjacent to LRAFB.

I suffer from several of the medical conditions listed as being caused or contributed to by Agent Orange chemicals. My wife and our first son, who was a toddler playing in the orange dirt, have medical issues.

I have attempted to file for acknowledgement for the chemical hazards located at LRAFB and in Jacksonville a few times through the VA system, all with denied claims results. Even after the area was identified as a Superfund clean-up site, the denials still came.

My guess as to why the claims have constantly been denied is because acknowledgement of the claims would open a hornet’s nest for the government.

I lived in Jacksonville, across from Vertac, from February to August 1981, then on LRAFB from August 1981 until 1986, then in Jacksonville from 1986 to 1989. I was a Titan II Missile launch officer. In 1983, my wife miscarried. In 1985, my son was diagnosed with leukemia. In 1985, I developed massive cluster migraines and periodic fevers. In 1985, my neighbors wife had a stillborn, and also another neighbor miscarried. My son died in 1989 at the age of 8. He was one of several children in Jacksonville who got leukemia. No one in my family had a history of leukemia. We fished a lot in the base lake, ate the fish, swam in the water. There was a creek we were told was contaminated, but the U.S. never told us not to eat fish from the base lake, which I am sure had groundwater run-off from Vertac. I am now 58 and have neurological disorders I should not have at my age. No telling how many people came through LRAFB during Vertac years. I always believed that there were probably many more cases of illness caused by toxins in the waters, but due to the transient nature of the military, we will never know.

Our family purchased 397 acres in 1969 on Pension Mountain in Carroll County. In 1971/2 my uncle hired a company to spray the property to kill the trees etc. He and his family lived in Dallas, Texas, and we lived on the property in what’s called the Applegate ford. My first experience with the defoliant was mid-morning when a helicopter was spraying defoliant some 200 yards from our house. I could hear the trees screaming is the only way I can describe it. I loaded a rifle to shoot the helicopter down, but a hippie that was living there grabbed the rifle from my hands. I was sobbing, as I knew nothing about my uncle hiring the company to spray defoliant. I was twelve years old. Our neighbor had his 1,280 acres sprayed. Our land was sprayed three times. Over the next two to three years, I would see and hear of helicopters/ planes spraying the forests all over the Pension mountain area. A man with a master’s degree in chemistry who was a teacher in Berryville told me a few years later that there were six miscarriages by women living on the mountain area in the time of the spraying. I attended my sixty-one-year-old sister’s memorial service this past February. Cause of death was never fully determined. Asking about a family that I knew while there, I was told three of the children had died of cancer. I’ve kept track to the best of my ability and the number of deaths to population on children who were pre-puberty during the years of the sprayings is enormous. To the best of my knowledge, an area of 8,000 acres was sprayed in those few years. I’m fifty-eight and disabled, and I’ve had health problems that I believe are related to the defoliants. With the Vietnam war ending, they had an untold amount of these chemicals that they had to dispose of any way they could.

I was stationed at Little Rock Air Force Base from 1977 through 1981. I, my wife, and two children lived in an apartment complex on Marshall Rd. near Main St. We lived probably about a half mile from a processing complex on Marshall Rd. from Oct. 1978 until July 1981 (near the Vertac Site). In 1990, my youngest son developed large boils under the armpits, which still reoccurred into 2005. My oldest son recently lost a testicle due to a growth. In 1993, I had a Neurilemmoma tumor removed from the left side attached to a kidney. I’ve had two stokes since 2000. Dont know of any problems with my ex-wife who lived with us on Marshall Rd.