calsfoundation@cals.org

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS)

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) in Little Rock (Pulaski County) is Arkansas’s premier research hospital. UAMS provides the state with a solid foundation of higher learning and financial support. It has a long history of serving the public by providing the indigent with quality healthcare and is one of the largest employers in Arkansas, providing almost 9,000 jobs, many of them professional.

To some extent, the history of UAMS is the history of medicine in Arkansas. The Arkansas State Medical Association, formed in 1870, pressed the legislature to allow the legal dissection of cadavers—a major milestone in medical research and education. After the legislature’s approval in 1873, the state’s first dissection, performed by Drs. Lenow and Vickery, took place in the fall of 1874 at the Little Rock Barracks (now MacArthur Park). A memorial stands there to this day.

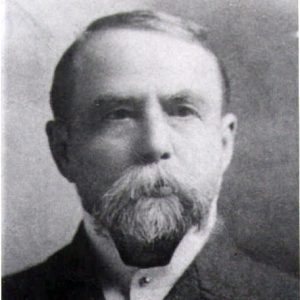

In the next few years, the doctors of the College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Little Rock and Pulaski County Medical Society collaborated to found a medical college. These two groups of physicians had been at odds over a seemingly insignificant but disruptive personal dispute in 1874, but the passing years and the prospect of a medical college brought them together into the larger State Medical Society by 1879. The soon-to-be college was nearly incorporated into St. Johns’ College but instead was invited under the roof of Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County)) in 1879 because of the efforts of Philo O. Hooper, head of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and General Daniel Harvey Hill, university president. The new Medical Department was an independent part of the university; Hooper was to choose the faculty, staff, and curriculum, and the university would not financially support the department—that is, no state appropriations for the university would go to the Medical Department.

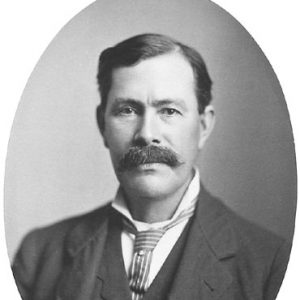

The Medical Department was incorporated in September 1879 with capital of $5,000 provided by eight investors, enough to buy the Sperindio Hotel at 113 West Second Street. Those eight—Hooper, Claibourne Watkins, James Southall, James Dibrell, John McAlmont, Roscoe Greene Jennings, Augustus L. Breysacher, and Edwin Bentley—became chairmen of the Medical Department. That fall, the department accepted twenty-two students. Much of their education came in the classroom, but they gained practical exposure to medicine by working in the dispensary in the Fones Hardware Store next door.

The Medical Department was touched with the racial tension that pervades Arkansas history. The first dissection, and most thereafter, was of an African American. Though there is no evidence that the Medical Department obtained these bodies illegally, the African American community held it in distrust. For example, after a body was discovered missing at a local cemetery, a Black detective obtained a warrant to search the Medical Department for the corpse. During the search, students filled the detective’s overcoat with the toes and fingers of their cadavers.

In 1911, the state merged the Medical Department with a competing Little Rock medical school, the College of Physicians and Surgeons, which was founded in 1906. (Not to be confused with the original College of Physicians and Surgeons, which was simply an association of physicians; this was an actual medical school.) The fundamental makeup of the department was changed: UA had a more direct role in educating budding physicians, while the new Medical Department, which had previously been an utterly separate entity, would receive state appropriations. This change was fomented by the American Medical Association’s recommendations to improve medical education standards, which both colleges failed to meet.

Despite state funding, the Medical Department foundered for years. Its facilities were notoriously poor. Arkansas was not a rich state; approving taxes for any purpose was difficult, and securing appropriations from the state was a never-ending struggle. Moreover, in the early twentieth century, scientific inquiry was a low priority for many Arkansans.

While the medical school was renamed in 1918, help did not come until the poverty of the Great Depression sparked President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1933. The administration freed half a million dollars to build a facility across from MacArthur Park. Today, that building houses the University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law.

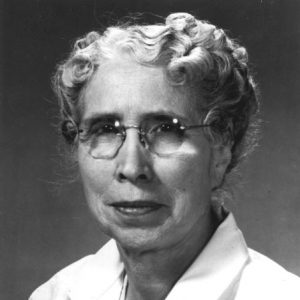

Returning to the racial problems that plagued mid-twentieth-century Arkansas, the Medical School admitted Edith Irby, its first African American student in 1948, nine years before Central High School’s desegregation. By state law she was forced to eat in a separate dining room and use separate bathrooms. In 1985, Irby became the first female president of the National Medical Association.

In 1956, the Medical School moved to its current location on West Markham Street, a fully modern facility (though it lacked air conditioning until 1966) dubbed University Hospital. The next year, the Schools of Pharmacy and Nursing were operational.

Until 1957, the Medical School accepted only indigent patients. Because of this, the number of types of patients was limited, so the students learned about the proper number of patients necessary for a sound medical education. To provide financial support and better education, the legislature approved a program to accept paying patients into University Hospital in 1965. The hospital thus changed from a charity hospital to a teaching hospital.

In 1979, the school’s organization was reformed again. The four professional schools—Medicine, Pharmacy, Nursing, and Health Related Professions—were deemed colleges under the control of a chancellor. The name University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences was adopted, and it was considered an independent campus of the University of Arkansas System. Its legacy of service, education, and research continued to expand. Total student enrollment in September 2011 was 2,819.

On June 29, 2012, UAMS ended its affiliation with Central Arkansas Radiation Therapy Institute (CARTI) to become the exclusive provider of radiation oncology services on campus. Radiation services are provided in the new UAMS Radiation Oncology Center, part of the UAMS Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute.

In July 2012, UAMS announced that it will open a dental education center, which will include an oral health clinic and post-graduate dental and oral surgery program. UAMS’s research indicated that Arkansas ranked fiftieth among states in number of dentists available per 100,000 people, and UAMS hoped that the new center will attract more dentists to underserved areas of the state.

In the fall of 2014, enrollment at UAMS was 2,890; some of these students were enrolled at the UAMS Northwest campus, which began operating in Fayetteville in 2007.

In May 2023, UAMS opened a new, four-story facility for orthopedic surgery, pain management, and spine care. In September 2023, it opened the Proton Center of Arkansas on its Little Rock campus to provide proton radiation therapy to children and adults with cancer. Part of the $65 million, 58,000-square-foot UAMS Radiation Oncology Center that opened in July 2023, the Proton Center was built in partnership with Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Baptist Health, and Proton International.

According to a September 2023 investigative report from the news network CNN, since 2019, UAMS sued more than 8,000 patients (including many UAMS employees) to collect on unpaid bills, filing more lawsuits for debt collection than any other plaintiff in the state besides than the state tax office. UAMS filed thirty-five lawsuits in 2016 but more than 3,000 in 2021, most involving unpaid bills of $1,000 or less. In addition, it added court filing fees, attorney and service fees, and interest charges, and garnished wages and bank accounts. In an interview, the chancellor said he had not been aware of the number of employees UAMS was suing until CNN gave him the information, and he said the university had begun looking at its collections policy. But he argued that the lawsuits were crucial to the institution’s finances, especially as it was suffering budget shortfalls and layoffs. The increase in lawsuits appeared to correlate with UAMS beginning to work with Arkansas-based debt collection firm Mid-South Adjustment Company in 2019.

Enrollment in the fall of 2023 was reported as 3,275.

For additional information:

Baird, W. David. Medical Education in Arkansas. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1979.

Baker, Max L., ed. Historical Perspectives: The College of Medicine at the Sesquicentennial. Little Rock: Arkansas Sesquicentennial Commission, 1986.

Langhorne, Will. “UAMS Opens $85M Spine Hospital.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 9, 2023, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/may/09/uams-celebrates-opening-of-orthopaedic-and-spine/ (accessed September 12, 2024).

Tolan, Casey, and Ed Lavandera. “Arkansas Hospital Sued Thousands of Patients over Medical Bills during the Pandemic, including Hundreds of Its Own Employees.” CNN.com, September 8, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2023/09/08/us/arkansas-hospital-debt-collections-lawsuits-pandemic/index.html (accessed September 12, 2024).

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. http://www.uams.edu (accessed September 12, 2024).

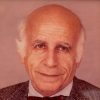

Jerry Puryear

Marion, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.