calsfoundation@cals.org

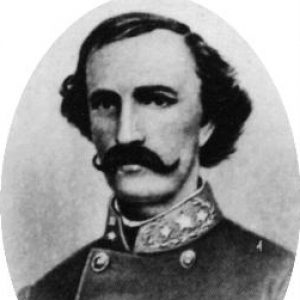

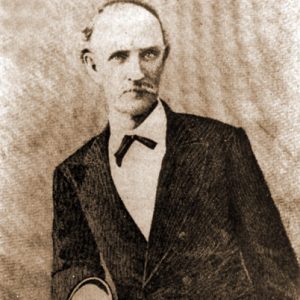

Thomas James Churchill (1824–1905)

Thirteenth Governor (1881–1883)

Thomas James Churchill, the thirteenth governor of Arkansas, led advances in health and education while in office. During his administration, legislation set standards for practicing medicine and established the Medical Department of Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) in Little Rock (Pulaski County). In addition to creating a facility for the mentally ill and a state board of health, his administration appropriated funds for purchasing a building for the branch normal school in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), which served African American students.

Born on March 10, 1824, on his father’s farm near Louisville, Kentucky, Thomas J. Churchill was one of sixteen children born to Samuel Churchill and Abby Oldham Churchill. The children grew up on the farm and attended Kentucky public schools. Churchill attended St. Mary’s College at Bardstown, Kentucky, and graduated in 1844 at the age of twenty. He continued his education by studying law at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky.

Churchill enlisted as a lieutenant in the First Kentucky Mounted Riflemen at the outbreak of the Mexican War in 1846. On the march to Mexico, his unit stopped briefly in Little Rock at the home of Judge Benjamin Johnson, where Churchill met his future wife, Ann Sevier, the daughter of Senator Ambrose H. Sevier and the granddaughter of Judge Johnson. While Churchill was a member of a scouting party in January 1847, Mexican cavalry captured him and his fellow soldiers and held them prisoner in Mexico City. Late in the war, an exchange of prisoners brought Churchill back to his command. Upon completion of his service, he moved to Little Rock and married Ann Sevier on July 31, 1849. They had two sons and four daughters.

Churchill owned a plantation near Little Rock and, in 1857, was appointed postmaster of Little Rock by President James Buchanan. He served as postmaster until 1861. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Churchill raised the First Arkansas Mounted Rifles and led the regiment at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, on August 10, 1861. In recognition of his service, his superiors promoted him to brigadier general in March 1862.

Churchill fought at the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas and at Richmond, Kentucky, before serving as the Confederate commander at Arkansas Post (Arkansas County). On the morning of January 9, 1863, Confederate pickets informed General Churchill that a large Union force with a fleet of gunboats was passing into the Arkansas River. Major General John A. McClernand and Admiral David Porter commanded a Federal force of about 32,000 soldiers and a naval escort of transports and ironclads with a mission to capture Arkansas Post. Churchill could only muster about 3,000 Confederate soldiers to defend the fort.

Despite such odds, Churchill ordered his troops into the lower trenches and awaited the Union onslaught. The Federal fleet of gunboats commenced moving up the river at 9:00 a.m. on December 10 and opened fire on the rebel defenders. Having only one battery, Churchill did not return their fire in hopes that the guns in Fort Hindman would respond. Unfortunately, the gunpowder at the fort was defective. As Churchill wrote, the fort’s guns “were scarcely able to throw a shell below the trenches much less to the fleet.” Around 2:00 p.m., Churchill discovered Federal cavalry and artillery approaching cautiously on his flanks. The Confederates fell back to an inner line of entrenchments and held off an assault just before darkness settled over the grounds.

The final attack began about noon on January 11 when the Union army pressured the Confederate line of defense by land and water. After three hours of artillery fire from the ironclads, the cannon in the fort fell silent. From their rifle pits, Churchill and his small command continued to hold off the Federal troops on the land until white flags appeared, and the defenders surrendered. Churchill spent the next three months at Camp Chase in Ohio as a prisoner of war, where he received horrible treatment; his troops spent several months as prisoners before being exchanged and joining Major General Patrick Cleburne‘s division in the Army of Tennessee.

Churchill returned to the Trans-Mississippi after his release and took command of an Arkansas infantry division. During the Red River Campaign in 1864, he fought at Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, on April 9. His command included Arkansas and Missouri infantry with orders to flank the Union command of Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, but a Federal counterattack blunted the assault. Soon after the battle, General Edmund Kirby Smith, the commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, sent Churchill’s division back to Arkansas to help defeat Major General Frederick Steele’s Union troops.

On April 30, the Arkansas infantry division under Churchill marched in the early morning hours through heavy rains and ankle-deep mud to attack the Federals at 8:00 a.m. at Jenkins’ Ferry in Arkansas. Union engineers completed a pontoon bridge across the Saline River, allowing the Union troops to fall back to Little Rock without a Confederate pursuit. Churchill received a final promotion to major general on March 18, 1865.

Churchill returned to his farm near Little Rock after the war but remained active in state politics. He supported Elisha Baxter during the Brooks-Baxter War in 1874 by enrolling volunteers in Baxter’s militia. As the Arkansas Republican Party self-destructed, the Democratic Party regained control of the state with the election of Augustus Hill Garland as governor and Churchill as state treasurer in 1874. Serving a total of three terms as state treasurer, Churchill was the Democratic Party candidate for governor in 1880 and easily defeated his opponent from the Greenback Party, W. P. “Buck” Parks. Allegations of financial malfeasance while Churchill was state treasurer did not arise until after the election and his inauguration. Despite important achievements during his tenure, the financial scandal haunted his administration.

Important legislation enacted during Churchill’s term as governor included a tax to fund the construction of a facility for the mentally ill. Besides establishing regulations for the practice of medicine in Arkansas, the legislature authorized the creation of the Medical Department of Arkansas Industrial University in Little Rock and created a state board of health. An appropriation of $10,000 went to purchasing a building for the branch normal school for black students in Pine Bluff, now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB), which had been renting space up to that point. There was even a resolution regarding the pronunciation of the state’s name, which concluded that Arkansas “should be pronounced in three syllables, with the final ‘s’ silent, the ‘a’ in each syllable with the Italian sound, and accent on the first and last syllables.”

The legislative session of 1881 appointed a committee to look into accusations of discrepancies in the state treasury between 1874 and 1880, the years Churchill served as state treasurer. The initial committee report concluded that $114,587 was missing from the treasury. A second report increased the total to $233,616. He faced a lawsuit in Pulaski Chancery Court after leaving office. Churchill’s attorneys argued the alleged shortages were due to bookkeeping errors and because the state debt board unintentionally burned scrip without crediting the treasurer’s account. While these arguments were probably true, Churchill eventually paid $23,973 to the state of Arkansas, although there was no admission of guilt.

Another problem for Governor Churchill involved Perry County, where differences between County Judge L. M. Harris and his political opponents led to threats and property damage. The judge eventually asked for the governor’s help in combating the lawlessness. Churchill sent the state militia into Perryville (Perry County), where it remained for three weeks doing nothing. Throughout the remaining days of Churchill’s administration, political opponents harped on the treasury shortage and the occupation of Perry County by militia, which reminded the citizens of Arkansas of Governor Powell Clayton’s use of the militia during Reconstruction. Politically weakened, Churchill completed his term and retired to his farm. He did not seek public office again.

For several years, Churchill lived quietly in Little Rock while retaining an interest in state, national, and international affairs. He once sent a telegram to Senator James H. Berry of Arkansas, offering his services to the president of the United States during a diplomatic crisis. When asked why, he replied, “I did this to show that the South and all the old Confederates are loyal to the Union and are willing and ready to defend the Government from all foreign foes….” The final years of his life included an interest in the United Confederate Veterans organization, in which he served as the major general of the Arkansas division in 1904.

Shortly after his eighty-first birthday, Churchill died in Little Rock on May 14, 1905, after a prolonged illness. As he requested, Churchill had a military funeral with full honors and was buried in Mount Holly Cemetery wearing his Confederate uniform.

During the 1928 National Convention of the United Confederate Veterans in Little Rock, Joseph S. Utley, commander of the Robert C. Newton Camp, delivered an address upon the unveiling of a memorial boulder in Little Rock honoring Churchill. In conclusion, Utley stated, “The example of his life will be an inspiration to us who hold dear the priceless heritage of his valor and his glory. And as in future years we come to this sacred shrine, we shall stand in silence with uncovered head, receive a fresh baptism of patriotic fervor, and go forth determined that no act of ours shall dishonor the memory of our intrepid leader.”

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin C. Steele’s Retreat from Camden and The Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry. Little Rock: Pioneer Press, 1967.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Hewitt, Lawrence Lee, Arthur W. Bergeron Jr., and Thomas E. Schott, eds. Confederate Generals of the Trans-Mississippi, Vol. 1: Essays on America’s Civil War. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2013.

Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959.

Don Montgomery

Prairie Grove Battlefield Historic State Park

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.