calsfoundation@cals.org

Sterling Robertson Cockrill Jr. (1925–2022)

Sterling R. Cockrill Jr. was in the insurance business with his father, Sterling R. Cockrill, in 1956 when he decided to run for one of Pulaski County’s eight seats in the Arkansas House of Representatives and was elected. Handsome and collegial, but soft-spoken, Cockrill was instantly a promising political star. However, in 1970—by which time he was the Democratic majority leader of the Arkansas House of Representatives, a former speaker of the House, and a leading prospect for governor—Cockrill suddenly joined the Republican ticket with Governor Winthrop Rockefeller and ran for lieutenant governor. His and Rockefeller’s lopsided defeat in 1970 by Democrats, after his defection from the party, signaled that his political career was over, and he never again ran for office or became strategically involved with either political party.

Sterling Robertson Cockrill Jr. was born on April 7, 1925, in Little Rock (Pulaski County), the middle of three children of Sterling Cockrill and Helen Bracy Cockrill. He graduated from Little Rock High School (now Central High School) in 1943, briefly attended Arkansas A&M College (now Southern Arkansas University) in Magnolia (Columbia County), and went into naval-officer training at Northwestern University in Chicago as World War II in Europe was winding down. The midshipman was sent to the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific Theater before the war came to an end.

He returned to Arkansas, attended the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), married classmate Adrienne Storey of Little Rock, and graduated in 1948. When the Korean War broke out in 1950, he was dispatched to Guam for another year of naval duty.

Cockrill’s forefathers—most of them also named Sterling—went back six generations to Chester Ashley, who joined Arkansas’s first law firm and became perhaps the wealthiest man in antebellum Arkansas before being elected U.S. senator. Ashley’s grandson (and Cockrill’s grandfather), also named Sterling Robertson Cockrill Jr., was elected chief justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1884.

Cockrill took a seat in the Arkansas legislature in January 1957, the same year that Little Rock’s public schools were slated to desegregate, starting that September with Central High School. The legislative session of early 1957 saw the introduction of bills intended to discourage the implementation of school integration; in fact, a constitutional amendment adopted by Arkansas voters in 1956 seemed to mandate such steps (called interposition), including the creation of a state Sovereignty Commission that would advance the cause of permanent racial segregation and the defiance of the Supreme Court orders. Cockrill and a number of other lawmakers resisted some of the legislation, although only one representative—Cockrill’s friend Ray S. Smith Jr. of Hot Springs (Garland County)—finally cast a vote against any of the four major segregation bills when the roll was called.

By that fall, however, after Governor Orval Faubus sent National Guard soldiers to Central High School to block the entrance of nine Black students, the political climate had made such stands even more politically implausible. No elected officials, with the temporary exception of the mayor of Little Rock and a rare state legislator, dared for several years to oppose any legislation or executive action that was intended to prevent integration of the schools or public facilities, including a bill to close Little Rock high schools in 1958 to prevent Black students from enrolling. Only Smith voted against the school-closing bill.

Faubus retired at the end of 1966. In January 1967, the House elected Cockrill the speaker. Winthrop Rockefeller, who had energized the moribund Republican Party and then was beaten by Faubus in the 1964 governor’s race, defeated the segregationist hotspur Jim Johnson in 1966 and became governor on the same day that Cockrill became the leader of the House. Rockefeller had run on the promise of creating an “Era of Excellence” in which Arkansas’s education, economic, highway, and public-health systems would be transformed from the poorest in the country (alongside Mississippi and West Virginia) into parity with the educated and flourishing states of the east and west. But Rockefeller tried and accomplished little in his first term beyond trying to reform the state’s brutal and corrupt prison system. Cockrill politely but publicly berated him for failing to undertake the reforms that he had seemed to promise in his inaugural address.

Cockrill surfaced from the legislative sessions of 1967 as the likeliest Democratic candidate to oppose the Faubus machine candidate for governor, Representative Marion H. Crank of Foreman (Little River County), in the 1968 Democratic primaries. Cockrill said Rockefeller had promised but had not delivered reforms, especially in public education. In the end, Cockrill backed out of the governor’s race, and lawyer Ted R. Boswell of Bryant (Saline County) became the progressive Democratic candidate. Boswell was narrowly squeezed out of a runoff with Crank, who received the Democratic nomination and lost narrowly to Rockefeller in November.

In his inaugural address to the legislature to start his second term in 1969, Rockefeller proposed the most far-reaching and liberal economic program in the state’s history. He proposed graduating the state’s personal income tax—which had been capped at five percent since its enactment in 1929—so that it taxed the state’s richest citizens, including himself, at twelve percent, which would have been the highest rate in the country, while lowering taxes on poorer people, and raising the corporate income tax from five percent to a flat rate of seven percent. He proposed raising a variety of excise taxes and broadened sales taxes—altogether a fifty-percent increase in the general revenues of the state—to pay for upgrading the poorer schools and teacher salaries, beginning universal kindergartens in all the schools, expanding community colleges and technical schools, and raising the state subsidies for public colleges. Fuel taxes would be raised to beef up the highway system. The state would take advantage of healthcare subsidies for the poor offered by the Medicare and Medicaid act of 1965.

Rockefeller’s massive program landed with a thud. Of the 135 legislators, all but five—one in the Senate and four in the House—were Democrats. Except the corporate income tax, which received a majority but not the required supermajority in the Senate and a good but not prevailing vote in the House, the major tax bills went down to dramatic defeat, usually with the votes only of the Republican sponsors and a few Democrats, although Cockrill was the majority leader. Cockrill supported much of the tax program and managed several of the bills in the House, although he declared that the governor’s tax package was larger than the legislature politically could pass. He had little sway within his party in the House, still dominated by the “Old Guard” that had supported Faubus and the continuation of racial segregation and low taxes.

After most of Rockefeller’s big program was either defeated or blocked in committee, Cockrill, his friend Ray S. Smith Jr., and Speaker Hayes C. McClerkin of Texarkana (Miller County) put together a very modest tax program—about a fifth of the revenue Rockefeller sought—and passed the bills in both houses, including raising the corporate income tax from five to six percent. Rockefeller refused to sign the bills but let them become law without his signature. He did the same with major appropriation bills. He said he could not bestow his blessings on legislation that fell so far short of the state’s needs. He called the legislature into special session the next year and tried again, also without any success. Late in the 1969 session, conservative Democrats in eastern Arkansas circulated a petition among House members to take the title of majority leader from Cockrill, owing to his vocal support of much of the Rockefeller program, but the petition drive stalled without getting the signatures of even close to a majority of the Democratic House members.

Rockefeller had promised to serve only two terms, but he announced in the summer of 1970 that he would run again because the legislature had not enacted the programs that he had promised, and he thought people in the state wanted to be lifted from the state’s historic doldrums and for him to try again.

Faubus had announced that he was coming out of retirement to regain the office that he had held for a dozen years. Cockrill publicly toyed with the idea of running for governor in 1970, but he expected Faubus to win the party’s nomination again, thwarting his own aspirations and also the prospects of realizing economic goals that he shared with Rockefeller. Cockrill’s college friend, fraternity brother, and next-door neighbor Lieutenant Governor Maurice L. “Footsie” Britt was ready to give up the role of Rockefeller’s running mate and potential successor. Rockefeller and Britt talked Cockrill into switching parties and joining the Republican state ticket in the approaching election. Cockrill said he would run for governor if Rockefeller did not. When Rockefeller announced that voters expected him to run and try again to pass his economic program, Cockrill filed for lieutenant governor, and they ran as a team. Despite changing his allegiance to the Republican Party, however, Cockrill did not hesitate to rebuke publicly Vice President Spiro T. Agnew, who at a speech at Fort Smith (Sebastian County) had called the American news media and national Democratic leaders “supercilious sophisticates” of the left who were trying to destroy America. Cockrill said Republicans should not tolerate such language from one of their national leaders.

Faubus did lead the ticket in the Democratic preferential primary of 1970, but there were seven other candidates, and the least known of them, Dale Bumpers, a lawyer in the small town of Charleston (Franklin County), squeezed into the runoff with Faubus and defeated him in a landslide. In the general election, his landslide against Rockefeller was even larger. Bumpers also carried with him the Democratic nominee for lieutenant governor, Bob Riley, another old friend of Cockrill’s. Bumpers later said that if a young liberal like Cockrill or Ted Boswell had run for governor, he would not have run. Bumpers embraced much of the Rockefeller program and many more progressive legislative and executive initiatives, and he passed the most substantive program in the state’s history in 1971 and 1973.

Cockrill retired from politics after the election. He worked as an urban planner in the Little Rock office of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and was director of several organizations dedicated to revitalizing downtown Little Rock, including the Metrocentre Improvement District. He was a prolific artist, working in several media, including weathered barn wood.

He died on March 23, 2022, survived by his wife of seventy-six years, Adrienne Storey Cockrill, and two daughters. His ashes are interred at Mount Holly Cemetery.

For additional information:

“Cockrill Runs for No. 2 Post.” Arkansas Gazette, June 14, 1970, pp. 1A, 2A.

Finch, Jenny. “Sterling R. Cockrill: Concerned and Happy Citizen.” The Keepsakes Project. http://thispublicaddress.com/keepsakes/cockrill.html (accessed December 21, 2022).

Smith, Doug. “Cockrill Switches to GOP, Blames ‘Frustrations.’” Arkansas Gazette, April 17, 1970, pp. 1A, 8A.

Sterling Cockrill Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://cdm15728.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/id/6990/rec/1 (accessed January 4, 2022).

Sterling R. Cockrill Jr. Obituary. Ruebel Funeral Home, March 24, 2022. https://www.ruebelfuneralhome.com/obituaries (accessed December 21, 2022).

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Politics and Government

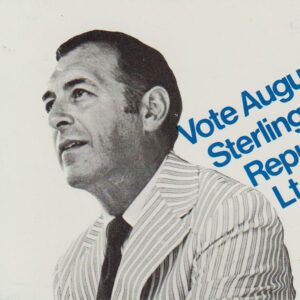

Politics and Government Cockrill Campaign Card

Cockrill Campaign Card  Sterling Cockrill Jr.

Sterling Cockrill Jr.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.