calsfoundation@cals.org

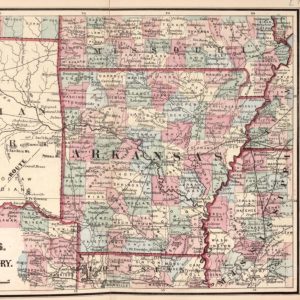

Public Land Surveys

The survey and division of the public lands that would make up the state of Arkansas was vitally important to the orderly settlement and development of the future territory and state. The modern survey system devised by the United States in the late 1700s provided the basis for subdividing the vast new lands acquired by the expanding nation into more identifiable, transferable tracts. Soon after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the U.S. government began the process of dividing the vast addition into smaller tracts, including the eventual survey and charting of nearly all of the newly acquired public land in the territory that would become Arkansas. That process in Arkansas would last nearly half a century.

Prior to 1815, the primary responsibility of public land surveyors in the Louisiana Territory was to assist governmental land boards to adjudicate private claims made by early settlers, migrants, and others seeking ownership of lands encompassed by the Louisiana Purchase. Most of the claimants asserted “squatters’ rights” or argued that they or their assignors had been granted enforceable land claims by the French and Spanish governments prior to 1803. Frederic Bates, a member of the St. Louis, Missouri–based board that oversaw claims in the Arkansas region, traveled to Arkansas Post in July 1808 to conduct one of the earliest private claim hearings in Arkansas. Government surveyors confirmed the boundaries of allowed claims.

During the Louisiana Territory and early Missouri Territory eras, the United States surveyor general had general surveying responsibilities in present-day Arkansas. In 1812, Congress established the General Land Office (GLO), which assumed primary responsibility for surveying all U.S. public lands surveys. That same year, Congress and the GLO directed the acting public surveyor in the Missouri Territory to begin the process of surveying and dividing the territory into identifiable tracts of six-mile-square “townships.”

In 1815, the GLO directed that a starting point for all public surveys in the Missouri Territory be established in eastern Arkansas, marked by the intersection of a newly surveyed “baseline,” which commenced at the mouth of the St. Francis River and ran due west, and the Fifth Principal Meridian, which commenced at the mouth of the Arkansas River in what would become Desha County and was surveyed to run due north. From this beginning point, public surveyors were instructed to follow a grid-based public land survey system that divided land first into townships, each identified with a township and range designation indicating its position relative to the beginning point (e.g., Township 10 South, Range 2 West). Each township was further surveyed and divided into thirty-six one-mile-square “sections,” which, in turn, were subdivided into quarter sections.

Three months after the establishment of the beginning point, Congress designated present-day Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas together as a new, massive surveying district and approved William Rector to serve as surveyor general of the district. Rector would serve in that position until 1824, when he was removed from the politically charged position, accused of nepotism and favoritism in awarding deputy surveying contracts. Despite his removal, Rector and the political dynasty known as “The Family” controlled much of the surveying activities in the district for many years, including in Arkansas. With this control, they enjoyed the political benefits attendant to the powerful office and the economic opportunities afforded surveyors having access to uncharted frontier lands.

In 1816, Rector and his office began locating and surveying two million acres of suitable land between the Arkansas and St. Francis rivers that Congress had directed should be awarded to veterans of the War of 1812. Because much of the land in the region was flood-prone or otherwise unsuitable for farming and habitation, however, the process of locating and surveying lands to meet the military bounty quota took many years. Moreover, most of the military claims, once awarded, were sold to land speculators. As a result, few veterans relocated to the area.

Before the military bounty land surveys were completed, the GLO directed Rector to commence surveys of some of the first lands in Arkansas that would be readied for sale to the public. In 1818, Rector entered into contracts with private surveyors for the survey of approximately sixty townships in southwestern Arkansas and in north-central Arkansas for this purpose. Government land offices were first established in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Batesville (Independence County) by 1822 to facilitate the sale of surveyed lands.

Public surveyors general, including those responsible for surveys in Arkansas, contracted the actual survey field work to private “deputy” surveyors, who would organize, equip, and compensate a small surveying crew, generally consisting of three or four members. The deputy and his crew operated under regulatory instructions issued by the surveyor general, who remained responsible for the accuracy of the work. Clerks in the surveyor general’s office—possessing varying degrees of math and drafting skills—were responsible for examining, certifying, or rejecting the survey work of the deputies and their crews. The reviews were based on extensive handwritten notes and calculations recorded during field work, including various measurements, descriptions of marks and monuments for corners, and detailed observations of the surveyed terrain. Plat maps of the confirmed surveys were then submitted to the GLO and the local land offices.

Much of the early survey work of Arkansas lands performed by the contracted deputies was of poor quality, however, either due to carelessness, faulty equipment, incompetence, or malfeasance, and a substantial amount of the initial effort was either rejected by the office of the surveyor general serving Arkansas or by the GLO in Washington DC. “Resurveys” of prior work were often necessary, delaying the efforts of the public land offices to place the Arkansas property into private hands.

Soon after the Arkansas Territory was established in 1819, its representatives urged Congress to designate the territory as a separate surveying district, arguing that surveying activity in Arkansas lagged behind that in Illinois and Missouri and that the establishment of Arkansas as a surveying district—overseen by a locally based surveyor general—would advance the transfer of public lands to private hands and thus promote the settlement and economic development of the territory. Congress did not establish the Arkansas Territory as a stand-alone surveying district, however, until 1832. President Andrew Jackson appointed James Sevier Conway as the first surveyor general of the new Arkansas surveying district. Conway located his office in Little Rock and served until 1836, when he resigned to run for political office, becoming the first governor of the new state of Arkansas.

By 1837, the boundaries of a vast majority of townships in Arkansas had either been demarcated at the hands of the public surveyors or were under contract for survey. However, much work remained, and the monumental effort of traversing the rugged terrain during all kinds of weather to document, mark, and chart more than 1,440 townships—as well as confirm the surveys and resurveys of the Arkansas public lands—would take decades to complete. Political infighting, cronyism, office clerk shortages, and budget constraints contributed to delays in the survey of the lands in Arkansas, and shoddy field surveying efforts resulted in the need to resurvey a considerable amount of Arkansas lands.

The Arkansas surveyor general’s office closed in 1859, despite protests from some that a considerable amount of the initial survey work merited re-examination. Today, most of Arkansas’s early public land survey records are in the possession of the Arkansas Commissioner of State Lands.

For additional information:

Arkansas Commissioner of State Lands. https://cosl.org/ (accessed November 26, 2025).

Beers, Henry P. French and Spanish Records of Louisiana: A Bibliographical Guide to Archive and Manuscript Sources. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989.

Bolton, Charles S. Arkansas, 1800–1860: Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Bragg, Don C. “General Land Office Surveys as a Source for Arkansas History: The Example of Ashley County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 63 (Summer 2004): 166–184.

Bragg, Don C., and Tom Webb. “‘As False as the Black Prince of Hades’: Resurveying Land in Arkansas, 1849–1859.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 73 (Autumn 2014): 268–292.

Rohrbough, Malcolm J. The Land Office Business: The Settlement and Administration of American Public Lands, 1789–1837. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Smith, David A. “Preparing the Arkansas Wilderness for Settlement: Public Land Survey Administration, 1803–1836.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly71 (Winter 2012): 381–406.

David A. Smith

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.