calsfoundation@cals.org

Prison Reform

The poor condition of Arkansas prisons has long been a subject of controversy in the state. The national prison system as a whole, and particularly in the South, was substandard up to the 1960s. Repeated scandal, evidence of extensive violence and rape, and violation of human rights brought national attention to Arkansas, placing pressure on the state to reform its penal system. Through a series of reforms beginning in 1967, the Arkansas prison system greatly improved, although issues of overcrowding still plague the state today.

Calls for prison reform began in the late nineteenth century, especially with regard to the system of convict leasing, whereby prisoners were rented out to labor for private enterprises, often in horrible conditions. Governor George Donaghey, elected in 1908, oversaw the dismantling of the convict lease system in Arkansas. At a 1921 penitentiary board meeting, activist Laura Conner demanded that the head warden of the Tucker Prison Farm be removed and a prison superintendent be instated to regulate prison conditions. Her motion was denied, but she continued to fight for prison reform throughout her life. In 1941, the Arkansas House of Representatives formed a committee to investigate conditions in Arkansas. The committee reported that the prisons served nearly inedible food, provided insufficient clothing, tolerated corruption and gambling, and beat and tortured the prisoners. Despite these findings, no measures were taken to improve the Arkansas penal system at that time.

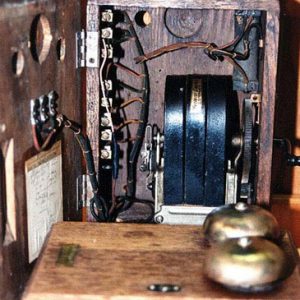

On January 16, 1967, newly elected governor Winthrop Rockefeller published a state police report on the prison system detailing events and conditions from August 19 to September 7, 1966. The investigation had taken place while Orval Faubus was still governor, but Faubus did not reveal the findings of the investigation. The report detailed the lack of food, the fourteen-hour work days, the violence, the rape, and the corruption within the prison. Some prisoners had been appointed as “trusties,” and they supervised the other prisoners. This system of convicts policing convicts contributed to the violence and corruption. The report also revealed the use of the “Tucker Telephone,” a torture device used to keep the prisoners in line.

During the police investigation, Tucker prison director Jim Bruton resigned from his position without warning. Although the police attempted to conceal from Bruton their true reason for investigating the prison, he fled during the first night of the investigation and never returned. Superintendent O. E. Bishop assumed control of the prison. In 1969, the federal government accused Bruton of nineteen counts of violating inmate rights and of torture. Of the nineteen counts, the federal government dropped ten, and the jury acquitted Burton of eight more. The remaining count resulted in a fine of $1,000 and a one-year prison sentence, which was suspended.

Gov. Rockefeller’s choice to publish the police’s findings initiated further investigation into the Arkansas prison system, led by the newly appointed superintendent, Thomas Murton. The continued investigation revealed the unsanitary conditions in the prison, particularly in the kitchen and dining room. The prisoners were underweight and overworked, and a disproportionate number died from diseases that they previously had no record of having.

In January 1968, Murton discovered three skeletons buried on the Cummins penitentiary property. His and many others’ immediate suspicion was that these were the bodies of abused and murdered Cummins inmates. Investigators worked to determine the identity of the skeletons, and while no credible information surfaced, it later appeared to be the case that the site constituted a pauper’s grave for deceased inmates not claimed by families.

Murton had an open communication policy with the media and faced the repercussions when he was fired by the Rockefeller administration for providing details of his findings to the public before formally reporting them to the state. Before he left his position, he found approximately 200 more skeletons buried in the Cummins graveyard, most of which could not be identified. Although Murton was fired after only eleven months of service, he made significant improvements at Tucker and Cummins. He stopped the use of the Tucker Telephone, improved sanitary conditions, and reduced rape and violence. In 1969, Murton published a book detailing his experiences with Arkansas prisons titled, Accomplices to the Crime: The Arkansas Prison Scandal. The film Brubaker, based loosely on Murton’s book, was released in 1980.

Murton’s discovery of “Bodiesburg,” as it came to be known, embarrassed the state and undercut the support for extensive reform movements that had been set in place. Before Murton’s discovery, the Rockefeller administration had made great progress toward prison reform, and Act 50 of the 1968 Arkansas General Assembly special session had the potential to improve Arkansas’s penal system significantly. However, with Murton’s discovery in the forefront of people’s minds in the state and the nation, support for reform floundered, and the Arkansas General Assembly failed to fund the reform plan.

Another outspoken prison reform supporter was Arkansas commissioner of corrections Robert Sarver. A group of inmates, including Lawrence J. Holt, filed a suit in the federal courts (Holt v. Sarver) regarding Arkansas’s prison conditions, with Sarver named as the respondent—despite Sarver’s actions on behalf of prison reform. On February 18, 1970, Federal Judge J. Smith Henley declared, in the case of Holt v. Sarver II, that the entire Arkansas prison system was unconstitutional, and he required Arkansas to undertake the task of prison reform. He banned the use of convicts as security officials or “trusties,” as well as the use of violence to subdue or control inmates. Furthermore, he banned the tolerance of contraband, gambling, and other forms of corruption.

After Henley’s decision, Arkansas made some attempts at reform, but none met Henley’s expectations. One of the most important changes occurred on July 1, 1970, when Arkansas replaced convict personnel with free-world personnel. Despite improvements, however, Arkansas prisons remained places of violence and corruption.

On June 1, 1971, the new commissioner, Terrel Don Hutto, assumed control over the Arkansas prison system. During his time as commissioner, he further expanded the personnel and security, as well as bettered conditions for inmates through improved education and work-release programs, bedding, and medical facilities. He also banned possession of guns by all inmates. Hutto created separate maximum security centers and rehabilitation centers, as well as units for the elderly and minor inmates.

In August 1981, the Eighth District Court conducted a hearing on conditions in Arkansas prisons in order to determine constitutionality. During the hearing, both inmates and prison officials testified as to the state of the prisons. The inmates asserted that, despite improvements, violence was still prevalent, and living conditions were unconstitutional. In return, the prison officials discussed the improved medical facilities and claimed that they had no knowledge of gang rape, violence, intimidation, or threats occurring within the prison.

After hearing all testimony, Judge Thomas Eisele ruled that the case against the Arkansas prison system would be dismissed in one year if officials continued plans for improvement. Eisele acknowledged that many problems remained in the prisons, but he felt that none warranted court oversight. The case was dismissed on August 20, 1982.

Arkansas prisons had improved since the late 1960s when Rockefeller publicized the prison report. However, serious problems still existed. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, what came to be known as the Arkansas prison blood scandal drew both national and international press to the Cummins Unit. An investigation in 1993 revealed that prison officials at the Cummins Unit had knowingly been collecting HIV-infected blood from prisoners and selling it around the world. In 1994, Arkansas became the last state to stop selling blood taken from prisoners. Despite the troubles, it was during these years that the Arkansas Department of Correction began working toward accreditation from the American Correctional Association, thereby standardizing the state’s prison system.

Overcrowding became an issue for Arkansas prisons as early as the 1970s but became a dramatic problem by the 1990s. During the 1980s, the national mood shifted and there was a strong demand for stricter, harsher punishment for criminals. The result of this shift was an increase in the number of prisoners nationwide. By 2011, more than 16,000 people were held in Arkansas prisons, with the number expected to increase rapidly. Approximately ten percent of the state’s budget was devoted to the upkeep of the prison system. Under such conditions, it was difficult for the state to maintain the reforms of the previous years.

In 2010, Governor Mike Beebe designated a committee, the Arkansas Working Group on Sentencing and Corrections, to investigate the prison system once again, this time with a focus on reducing overcrowding. In response to the investigation, Beebe and state senator Jim Luker worked to pass a prison reform bill through the Arkansas House of Representatives. The bill provided for lesser sentencing for nonviolent crimes, increased the number of inmates eligible for early parole, and expanded the parole system. These measures were intended to primarily keep only violent offenders in prison for extended periods of time, thereby reducing overcrowding.

The reforms proposed by Luker and Beebe’s bill had been suggested before, but many Arkansans, including the Arkansas Prosecuting Attorneys Association, felt that the bill was too lenient on criminals. In response to concerns over the practicality of the bill, Beebe and Luker implemented revisions designed to ease prosecutors’ concerns. Such revisions included improvements to the parole system, which would allow better monitoring of the released criminals, as well as more extensive treatment methods, particularly for those convicted of drug-related crimes. In light of the revisions, the Arkansas Prosecuting Attorneys Association, on March 4, 2011, publicly announced its support of the bill. On March 9, the Arkansas Senate passed the reform bill, followed on March 16, 2011, by the House of Representatives. Beebe gave his final approval on March 22, 2011, signing the bill into law. Without the bill, Arkansas projected spending more than one billion dollars on its prison system over the next ten years and having a prison population growth of forty-three percent. Instead, by reducing overcrowding, it was hoped that the bill would allow the state to provide humane conditions for prisoners while still saving the state an estimated $875 million over the next ten years. However, by August 2015, the state had one of the fastest growing prison populations in the nation, despite a decline in violent crime, and set a record for the number of inmates under its jurisdiction, 19,055; this was approximately 3,000 inmates above capacity. Moreover, Arkansas still ranks among the highest in the nation for lawsuits over the conditions of incarceration.

The Arkansas prison system has undergone perpetual reform since the late 1960s. While concerns still exist regarding the numbers and treatment of prisoners, the Arkansas penal system has greatly improved. The prison reform movement was largely due to Gov. Rockefeller’s intervention, which began a string of investigations revealing Arkansas’s desperate need for improvements in its antiquated penal system.

For additional information:

Crosley, Clyde. Unfolding Misconceptions: The Arkansas State Penitentiary, 1836–1986. Arlington, TX: Liberal Arts Press, 1986.

Flock, Elizabeth. “What’s the Matter with Arkansas? Prison and Jail Lawsuits Signal Trouble.” Al Jazeera America, October 14, 2015. http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/10/14/whats-the-matter-with-arkansas.html (accessed January 24, 2022).

Murton, Thomas O., and Joe Hyams. Accomplices to the Crime: The Arkansas Prison Scandal. New York: Grove Press, 1969.

Richard, Gregory L. “Lighting the ‘Dark and Evil World’: Judge J. Smith Henley, Arkansas, and the Federal Judiciary’s Reform of Southern Prisons.” In Nation within a Nation: The American South and the Federal Government, edited by Glenn Feldman. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2014.

———. “The Rule of Three: Federal Courts and Prison Farms in the Post-Segregation South.” Ph.D. diss., University of Memphis, 2013.

Smith, Ryan Anthony. “Laura Conner and the Limits of Prison Reform in 1920s Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 77 (Spring 2018): 52–63.

Urwin, Cathy K. Agenda for Reform: Winthrop Rockefeller as Governor of Arkansas, 1967–1971. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Woodward, Colin.”‘There’s a Lot of Things That Need Changin'”: Johnny Cash, Winthrop Rockefeller, and Prison Reform in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Spring 2020): 40–58.

Laura Choate

Conway, Arkansas

Jim Luker

Jim Luker  Prison Reform Meeting

Prison Reform Meeting  Johnnie Pugh Certificate

Johnnie Pugh Certificate  Winthrop Rockefeller

Winthrop Rockefeller  Tucker Telephone

Tucker Telephone

One place to curb overcrowding would be examining records for disciplinary actions for inmates and release those who maintain model prisoner status. Most model prisoners are a product of a spouse or other partners crime, i.e., living or partnered with an individual engaged in criminal activity. My sister was incarcerated for ten years because of her husband’s crimes. She turned down probation–pleading guilty when not guilty was unthinkable. Her husband died before trial, and the court tried her as though she were him. Her appointed attorney encouraged trial, saying, by law, they cannot convict,” but the attorney enabled conviction by intentionally making a directed verdict motion to enable her to challenge sufficiency of evidence.

I have witnessed a judicial system cloaked with corruption, and I believe it may be a prerequisite for employment nowadays. The good-ole-boys network is defined by owing favors and trading people like chips or pawns. Imagine if you were the next favor owed.