calsfoundation@cals.org

Petit Jean Rock Art Sites

Petit Jean Mountain in west-central Arkansas boasts a large concentration of ancient Native American rock art that includes, as of 2023, seventy-six known individual sites with more than 1,000 pictographs (rock paintings) executed in red or black pigments, as well as petroglyphs (rock engravings). The study of this cultural resource began in 1914 when the wife and son of Dr. T. W. Hardison, the founder of the Arkansas state park system, found rock paintings in a cave near their home on the mountain. The pictographs received national attention after 1923 with the establishment of Petit Jean State Park. Discoveries continue to this day, as most of the paintings have been documented just since 2006 with the advent of new photographic techniques. Of these seventy identified sites, the first eleven to be recorded were nominated in 1982 to the National Register of Historic Places, America’s official list of properties deemed worthy of preservation. These were thematic nominations included with the remainder of the twenty-eight Arkansas rock art sites, which were all that were known at the time in the entire state. Another site was added in 2006 for a total of twelve on Petit Jean Mountain. The original nominations resulted from a two-year survey by archaeologists Robert Ray and Gayle Fritz.

Despite difficulties in dating and interpreting the art, Fritz and Ray felt that rock art sites in Arkansas warranted inclusion on the National Register because of their assumed significance as ancient remnants of Woodland (600 BC to AD 1000) and Mississippian period (AD 900 to AD 1600) American Indian cultures. They feared that sites would cease to exist if not protected, writing: “Unfortunately, many rock art sites have disappeared due to destructive forces of nature and vandalism during the decades in which professionals largely avoided rock art research. These fragile resources are in desperate need of protection and investigation. It seems that the sites being nominated reflect ritual and probably for the most part spiritual aspects of the societies whose members created them. This in itself is significant given the few opportunities archeologists have to study remains of activities which can be identified as more than purely technological and economic.”

All of the Petit Jean Mountain rock art National Register sites are rock shelters, meaning that they are natural cavities in the mountain’s sandstone cap, although rock art can also be found on open expanses of sandstone bluff and isolated boulders. One of the twelve, Rock House Cave, serves as the lone publicized location for viewing rock art in Petit Jean State Park. The Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, in consultation with the Arkansas Archeological Survey, took this step to protect the locations of the numerous other vulnerable rock art sites while at the same time giving the public a spectacular gallery for viewing representative paintings and engravings. As a well-known location on popular hiking trails, it is regularly monitored, studied, and—the state hopes—better protected from vandalism.

Although some of Petit Jean Mountain’s archaeological sites are known by a popular name, such as Rock House Cave, they all have a unique designation that identifies the state, county, and numerical documentation sequence. Thus, for example, Rock House Cave is also referred to as 3CN20, meaning that in Arkansas (3), in Conway County (CN), it was the twentieth archaeological site documented. For the other sites, this system preserves their anonymity while giving them a unique scientific label for study.

The National Register sites occupy several distinct areas of Petit Jean Mountain. The common characteristic of these sites seems to be that they are sandstone shelters along natural thoroughfares. They exhibit a variety of sizes, opening orientations, distances from water, sunlight exposures, and unevenness of terrain. Some of the shelters appear very snug, while others seem as if they would have placed inhabitants or visitors at the mercy of the elements.

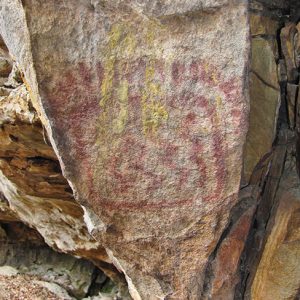

The artistic themes are as varied as the shelters. All twelve sites contain pictographs, but petroglyphs been discovered in only three. One of these carvings consists of engraved concentric circles at 3CN17, while an engraving in the Rock House is a rayed circle, and 3CN130 exhibits a figure that is pecked through the darker stone “varnish.”

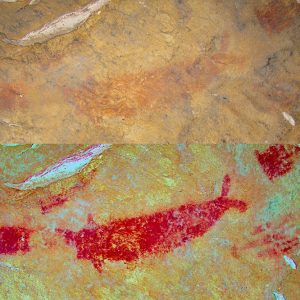

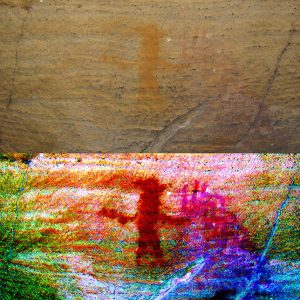

The hundreds of pictographs cover many themes, from realistic to abstract, from anthropomorphic (human-like) images and zoomorphic (animal-like) images to those assumed to depict tools, weapons, sun, moon, stars, and plants. Two of the best zoomorphs are an image at 3CN20 that is interpreted as a paddlefish and one at 3CN125 that may represent a beaver. Two recent and spectacular discoveries at 3CN17 and 3CN20 appear to represent stylized horned owls. The shelter 3CN17 includes plantlike forms that have been interpreted as maize and ferns. Several of the National Register rock art locations display variations of spirals as motifs, while at others, linear figures predominate. One of the earliest reported types, described by writer Raymond Torrey as layered “birthday cakes” and found at three of the sites, may depict ceremonial masks.

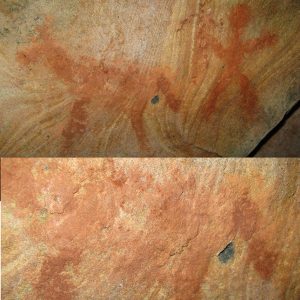

Unfortunately, documentation came late to some of the rock art locations. Pictographs at a site in the Seven Hollows area, known as 3CN129, are not ancient at all but only date to circa 1970, according to witness information. An image of a human and an animal were fingerpainted by hikers using streambed clay, and by the time the figures were documented ten years later, enough of the mud had washed off that researchers assumed they were aboriginal pictographs. Compared to all the authentic pictographs, however, only these retain the original binder—iron-rich clay—used to make them. Nevertheless, even these forgeries, given that the date of creation is known, are of use to scientists as a living experiment, since through the years they should continue to redden with the oxidation of the iron in the mud. Once this mud disappears and leaves iron-stain images, these pictographs may be indistinguishable from the ancient ones.

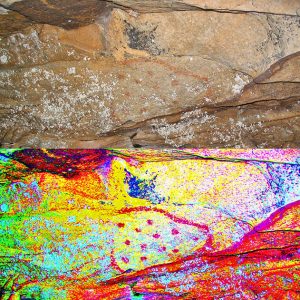

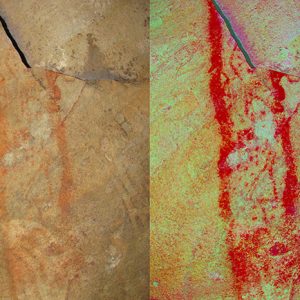

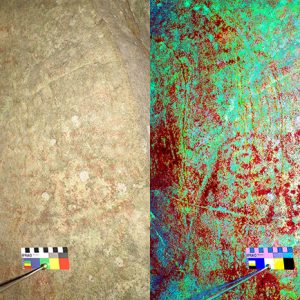

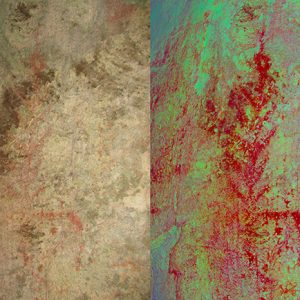

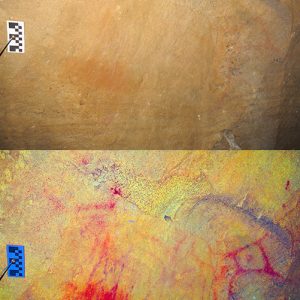

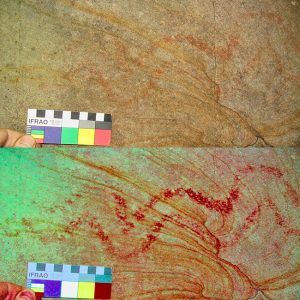

According to current Arkansas Archeological Survey counts, these twelve sites alone have more than 380 individual paintings and engravings, and as detection technology improves, more will be brought to light. One such advance has been a technique called decorrelation stretch, developed to isolate colors in aerial digital photography. Modified for rock art by Dr. Jon Harman as DStretch, a software application for rock art photography, its use has resulted in the discovery of dozens of new-to-science pictographs at these National Register sites. For example, 3CN17 was long thought to have an already-impressive twenty-four paintings, but through DStretch photographic enhancement, the known total at this site increased in 2014 to fifty-three, including the complex spiral image illustrated with this article. Similarly, in 2017 the number of documented paintings at the Rock House, 3CN20, more than doubled to the present number of 201.

Vandalism is the primary threat to these and other American Indian rock art sites. Although it is illegal to do so, visitors to Petit Jean Mountain and Petit Jean State Park continue to etch, paint, and mark names and other graffiti on the sandstone surfaces. They also engage in looting and digging to find and remove tools, worked stone, and other artifacts; in addition, some people have stacked rocks removed from these sites to create monuments to themselves in these sensitive places. Perhaps an increased awareness by the public of the value of these rare and special cultural resources and a reduced tolerance for these thoughtless behaviors will discourage further destruction.

For additional information:

Fritz, Gayle J., and Robert H. Ray. “Rock Art Sites in the Southern Arkansas Ozarks and Arkansas River Valley.” Arkansas Archeology in Review, edited by Neal L. Trubowitz and Marvin D. Jeter. Research Series No. 15. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1982.

Hardison, T. W. A Place Called Petit Jean: The Mountain and Man’s Mark. Little Rock: Carden Bottom Publishing, 1955.

Higgins, Donald P., Jr. “Three Hundred Pictographs: Dr. Hardison and a Century of Petit Jean Mountain Rock Art Discovery.” Arkansas Archeologist 53 (2014): 1–36.

Sherrod, P. Clay. Motifs of Ancient Man: A Catalogue of the Pictographs and Petroglyphs of a Portion of the Arkansas River Valley. Little Rock: University of Arkansas at Little Rock, College of Sciences, Office of Research in Science and Technology, 1984.

Torrey, Raymond H. “Describes Petit Jean State Park.” Arkansas Gazette, November 28, 1926, p. 6.

———. “More Pictographs Found at Petit Jean Mountain.” Arkansas Gazette, May 8, 1927, p. 11.

Donald Higgins

Petit Jean Mountain, Arkansas

Pre-European Exploration, Prehistory through 1540

Pre-European Exploration, Prehistory through 1540 3CN125 Exterior

3CN125 Exterior  3CN125 Rock Painting

3CN125 Rock Painting  3CN126 Exterior

3CN126 Exterior  3CN126 Pictograph

3CN126 Pictograph  3CN127 Exterior

3CN127 Exterior  3CN128 Exterior

3CN128 Exterior  3CN128 Pictograph

3CN128 Pictograph  3CN129 Exterior

3CN129 Exterior  3CN129 Pictograph

3CN129 Pictograph  3CN130 Exterior

3CN130 Exterior  3CN130 Graffiti

3CN130 Graffiti  3CN130 Petroglyph

3CN130 Petroglyph  3CN132 Exterior

3CN132 Exterior  3CN132 Site Painting

3CN132 Site Painting  3CN168 Exterior

3CN168 Exterior  3CN168 Painting

3CN168 Painting  3CN17 Exterior

3CN17 Exterior  3CN17 Pictograph

3CN17 Pictograph  3CN17E20 Rock Painting

3CN17E20 Rock Painting  3CN20 Exterior

3CN20 Exterior  3CN20 Rock Painting

3CN20 Rock Painting  3CN20 Rock Painting

3CN20 Rock Painting  3CN304 Exterior

3CN304 Exterior  3CN304 Pictograph

3CN304 Pictograph  3CN32 Exterior

3CN32 Exterior  3CN32 Rayed Circle Pictograph

3CN32 Rayed Circle Pictograph  Aboriginal Rock Art

Aboriginal Rock Art  Concentric Circles at 3CN17

Concentric Circles at 3CN17  Pictograph at Site 3CN20

Pictograph at Site 3CN20  Rock Art Panel

Rock Art Panel

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.