calsfoundation@cals.org

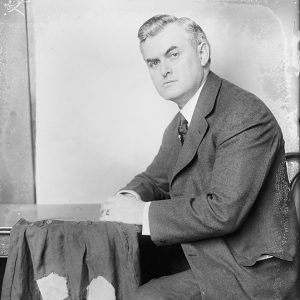

Otis Theodore Wingo (1877–1930)

Otis Theodore Wingo was a Democratic member of the U.S. House of Representatives. He represented the Fourth District of Arkansas in the Sixty-third through the Seventy-first Congresses, serving from 1913 to 1930.

Otis T. Wingo was born in Weakly County, Tennessee, on June 18, 1877, to Theodore Wingo and Jane Wingo. He received his early education in the local public schools before attending Bethel College in McKenzie, Tennessee; McFerrin College in Martin, Tennessee; and ultimately Valparaiso College in Indiana. Following college, Wingo taught school while he studied the law. He was admitted to the bar in 1900 and settled in De Queen (Sevier County), opening a legal practice there. On October 15, 1902, he married Effiegene Locke, and the couple would have two children: a daughter, Janie Blanche Wingo, and a son, Otis Wingo Jr.

After getting his practice established, Wingo ventured into politics, winning election to the Arkansas Senate, where he served from 1907 to 1909. During his legislative career, he developed a reputation as an outspoken figure, and in March 1907, the new senator urged the state legislature to ask Congress to repeal the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments. Later, he called for direct party primary elections as well as greater corporate taxation. During his Senate tenure, Wingo also successfully sponsored legislation to establish the Arkansas State Normal School, now the University of Central Arkansas (UCA) in Conway (Faulkner County). In 1934, his support for the school was memorialized when one of its buildings was named Wingo Hall in his honor.

Wingo left the legislature to return to his private legal practice, but he returned in 1912 to the political arena—this time at the national level. He successfully challenged incumbent congressman William B. Cravens for the Democratic nomination and then easily won the general election for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives representing the Fourth District.

During his time in Congress, Wingo was a member of the Banking and Currency Committee. From 1921 until his death, he was the ranking Democrat on the committee, and he was an outspoken advocate of currency reform. He also served on the Committee on Enrolled Bills, the Committee on Mines and Mining, and the Committee on Industrial Arts and Expositions. During World War I, Wingo served on the Committee on Expenditures of the War Department. In addition, he worked for federal flood control and farm relief legislation; authored a bill for the creation of a Ouachita National Park, which despite the additional strong support of Osro Cobb—the only Republican in the state legislature—fell victim to a pocket veto by President Calvin Coolidge; and worked toward the reduction of what he called “too much government” by pushing for the repeal of more than 40,000 laws.

A colorful populist, he engaged in some more quixotic crusades; one that reflected his direct approach and his opposition to excessive governmental interference was his opposition to daylight savings time, a venture he saw as an inappropriate tampering with nature. Indeed, in a 1918 effort to show how ridiculous he thought the idea was, Wingo suggested that Congress could provide for a winter thermometer to be placed in American homes that would set the freezing mark at forty-five degrees, thus making people think they were warmer and consequently saving fuel.

Such displays reflected his sometimes eccentric side, yet his belief in the importance of the individual, as well as his belief in standing up for the common man, was a constant. Nowhere was this more apparent than in his approach to international relations. On January 28, 1925, Wingo proposed that U.S. control of the Philippines was immoral given that it lacked the consent of the Filipino people. Arguing forcefully that the alleged “backwardness” of the Filipinos was not adequate justification for the American policy, Wingo declared: “I stand for independence of the individual, of the right of the community to govern itself.”

In 1926, Wingo was badly hurt in a car accident. He was unable to come into the office, and his wife became more involved, serving as the point of contact with his staff. Increasingly, Wingo counted on his wife to be his support, and during his later years, she served as his secretary and assisted in much of his congressional work. As his battle with gall bladder ailments intensified in the last four years of his life, she worked by his side daily, attending House sessions and committee meetings.

Wingo died on October 21, 1930, in Baltimore, Maryland, of complications after emergency gall bladder surgery. His dying wish was said to be that his wife succeed him in the House—as she did. Wingo is interred in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington DC.

For additional information:

“Democratic Committee to Select Wingo Successor.” Arkansas Democrat, October 22, 1930, pp. 1, 6.

Niswonger, Richard L. Arkansas Democratic Politics, 1896–1920. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

“Otis Theodore Wingo.” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=W000635 (accessed October 30, 2025).

“Representative Otis T. Wingo Dies Suddenly.” Arkansas Gazette, October 22, 1930, p. 1.

Shedd, Lindley C. “Effiegene Wingo: An Early Congresswoman from Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 67 (Spring 2008): 27–53.

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.