calsfoundation@cals.org

Osceola (Mississippi County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35°42’18″N 089°58’10″W |

| Elevation: | 234 feet |

| Area: | 9.42 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 6,976 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | January 12, 1853 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

317 |

458 |

953 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,769 |

1,755 |

2,573 |

3,226 |

5,006 |

6,189 |

7,892 |

8,881 |

8,930 |

8,875 |

|

2010 |

2020 | ||||||||

|

7,757 |

6,976 |

Osceola is located in northeastern Mississippi County on the Mississippi River, approximately fifty miles upriver from Memphis, Tennessee. Osceola is named for Chief Osceola of the Seminole tribe. Local historians have written that he visited the area in 1832 to explore the possibility of exchanging Florida land for Arkansas land, but no historical evidence supports this story. The community was the only county seat of Mississippi County until 1901, when Osceola and Blytheville were named dual county seats.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Originally acquired by the United States in 1803 as part of the Louisiana Purchase, the area was largely populated by Indians. The series of severe earthquakes on the New Madrid fault from December 1811 to February 1812 only temporarily slowed the flow of white settlers into the area. In 1830, William Bard Edrington and John Price Edrington bartered with Indians and took possession of a small group of huts along the Mississippi River, and by 1833, settlers had built log structures on the riverbank, which became a landing for travelers moving up and down the river. The oldest grave in Violet Cemetery dates back to 1831. The settlement was established as Plum Point in 1837, and in 1853, with 250 residents and a half dozen businesses, it was incorporated as Osceola.

When steamboats made their appearance on the Mississippi River, the Delta was opened to expanded activity and commercialization, and Osceola became an important landing. Timber was cut from the dense forests to fuel steamboats, the rich Delta land was planted in cotton, and a cotton culture soon emerged. Planters from nearby Southern states brought their lifestyle with them as they settled the area.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Osceola actively supported the secession of Arkansas from the Union in May 1861. Thousands of U.S. troops landed around Osceola in early 1862 in preparation for assaults on Fort Pillow and Memphis, but Osceola saw mainly skirmishes, guerrilla fighting, and raids. In May 1862, Confederate and Union naval fleets met in the Battle of Plum Point on the Mississippi River near Osceola. Osceola and Mississippi County were under martial law from November 1868 until March 1869 because of general lawlessness and instability. Racial disharmony and the activity of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) peaked during the Black Hawk War in 1872, following the death of Sheriff J. B. Murray at the hands of Charles Fitzpatrick, president of the Mississippi County Board of Registration. Charles Bowen, a local KKK leader and captain of the Confederate company Osceola Hornets, led a group of Klan members that killed a number of ex-slaves in Osceola after Fitzpatrick’s surrender and release led to a near-riot. The Black Hawk War was a violent finish to the disintegration of race relations in Mississippi County.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The golden age of steamboats on the Mississippi River came to an end as the last quarter of the nineteenth century approached. Small towns that were dependent on steamboats for their existence declined and died as railways took over. In contrast, Osceola, well positioned with both cotton and timber industries and with transportation by both river and rail, expanded. By 1890, Osceola began a sustained growth because of the industries and the river.

In 1897, Henry Phillips was lynched for the alleged murder of a white storekeeper. Afterwards, Leon Roussan, editor of the Osceola Times, publicly accused Sheriff Charles Bowen of encouraging the lynching; in response to the sheriff’s anger, Roussan had to leave the county for about a year, though his wife Adah Roussan continued publishing the newspaper. Two years later, Willis Sees was lynched for allegedly perpetrating arson.

Early Twentieth Century

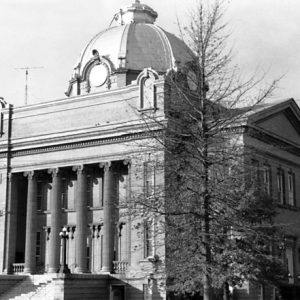

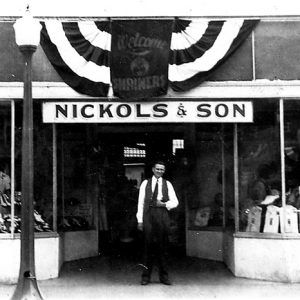

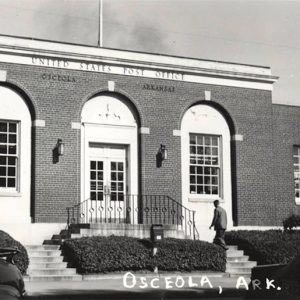

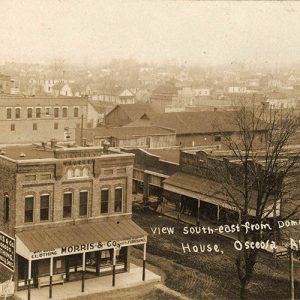

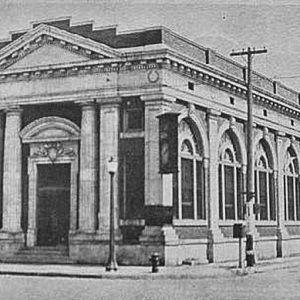

By 1900, Osceola was in a boom time. Railroads had taken the place of steamboats, and Osceola was on the main line of the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad. There were 953 residents, and downtown Osceola flourished with businesses that included an opera house, electric and water utilities, two ice plants, two bottling works, and a wagon factory. In 1901, a young white man named May Hearn was lynched downtown for having shot and killed another man “at a place of bad repute.” The Bank of Osceola was built in 1909. By 1913, Osceola was served by a Bell Telephone system and six daily passenger trains. Cotton was still the number-one crop, and farmland sold for $100 to $200 an acre. Many of the buildings constructed in that era are still used and are noted for their historic beauty. The 1912 Mississippi County Courthouse, with its solid copper dome and Neoclassical architecture, is on the National Register of Historic Places. The Patterson building, constructed in 1902 and 1904 to house Fred Patterson’s clothing and shoe store, is now used as the home of the Mississippi County Historical and Genealogical Society. The Osceola Times Building, built in 1901, is still used for the Osceola Times, which was first published in 1870 and is the oldest weekly newspaper in eastern Arkansas. The Planters Bank Building was constructed in 1920, and the Florida Brothers Building was built in 1936.

The Mississippi River, so vital to Osceola’s existence and growth, has been at times as much enemy as friend. The Floods of 1927 and 1937 brought vast devastation to Osceola. Hundreds of people lost their homes and belongings, and the cotton crops that were so important to the local economy were decimated. During both floods, thousands of refugees poured into Osceola, where Red Cross shelters were set up to receive and treat victims before their removal to Memphis. Comprehensive federal legislation was enacted as a result of the flooding. No main breech or overtop on the river has occurred since the 1937 flood, thanks to extensive work by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the St. Francis Levee District.

World War II through the Faubus Era

By the middle of the twentieth century, Osceola was in an era of prolonged growth. Population increased steadily from 1940 to 1960. Cotton was still the number-one money-maker in Osceola, but industry was increasing, and Osceola was thriving. The Ralston Purina Company operated a large cotton seed mill in Osceola, supplying jobs for over 100 employees. Osceola was a strictly segregated community; schools, movie theaters, restaurants, churches, public restrooms, and water fountains were “white only” or “colored only.”

Modern Era

Osceola’s growth and proximity to river transportation, railways, and the interstate highway system were attractive to manufacturing companies, and the city began accumulating a solid industrial base. In 1961, American Greetings Corporation built a large manufacturing facility in Osceola that remains the number-one employer in the city. Kagome Incorporated recently became the owner of Creative Foods, which was founded in 1948 as Osceola Foods, the oldest surviving manufacturing company in Osceola. The Plum Point Energy Station began producing electricity in September 2010. Osceola is certified as an Arkansas Community of Excellence by the Arkansas Economic Development Commission and has a very active chamber of commerce.

Osceola’s population is almost evenly divided between white and African-American residents, with black citizens slightly outnumbering white as of the 2010 census. Osceola has a high school, a middle school, and three elementary schools, which average a total enrollment of between 1,500 and 1,700 students.

Osceola’s relationship with the Mississippi River remains a close one. The river still defines Osceola, even though the city of today sits a few miles west of the river due to the relocation of downtown buildings from “Old Town” to “New Town” and the meanderings of the river. The Port of Osceola, once busy with steamboats, consists of a landing and grain elevators at Sans Souci that regularly load barges with soybeans and rice.

The growth of the steel industry in Mississippi County in the twenty-first century, including plants at Osceola, sparked a boom in housing developments in Osceola in order to provide homes to the workers moving to the city.

Osceola is one of the original five towns selected by Main Street Arkansas to participate in an economic and community development program to keep the downtown alive. Main Street Osceola sponsors the Osceola Heritage Music Festival each May. An annual parade and lighting of the Christmas tree is held by the City of Osceola at the Winter Festival each year on the Thursday after Thanksgiving.

Notable Figures

Ben Butler served as mayor for almost thirty years. Actress Dale Evans was raised in Osceola, and businessman Charles Wilson, who started the Holiday Inn hotel chain, was born in Osceola. Dwight Hale Blackwood was a minor league baseball player who, after retiring from the game, became involved with state politics. He had a successful career in public office, holding a number of positions in state and local government. William Reynolds Dyess was a politician and government official who headed the Arkansas operations for two New Deal agencies: the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Professional football player Maurice Carthon grew up in Osceola.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northeast Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishers, 1889.

Edrington, Mabel. History of Mississippi County. Ocala, FL: Ocala Start Banner, 1962.

Mississippi County, Arkansas: Through the Years. Osceola, AR: Osceola–South Mississippi County Arkansas Historical Heritage Documentation Committee, 1986.

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Caging the Blind Tiger: Race, Class, and Family in the Battle for Prohibition in Small Town Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 71 (Spring 2012): 44–60.

Worley, Ted. “Early Days in Osceola.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Summer 1965): 120–126.

Lonnie Strange

Washington County Historical Society

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.