calsfoundation@cals.org

Opera Houses

From the late 1800s through the 1920s, entertainment venues known as opera houses flourished throughout small towns in America. Arkansas had its share, with many communities constructing opera houses in an effort to display their town’s culture, permanence, and respectability. The buildings were called opera houses to set them apart from vaudeville-type theaters that were considered lower class. Opera houses in Arkansas generally seated a few hundred to a thousand people. They served as performance spaces for celebrity appearances, lectures, magic shows, musical events, and touring theatrical presentations, as opposed to the kind of grand operatic spectacles at such iconic locations as New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Many small-town opera houses attracted top-tier celebrities of that era such as Sarah Bernhardt and Mark Twain, along with lectures and traveling educational programs like Chautauqua. Most of the opera houses in Arkansas were converted into movie theaters in the 1920s. Few of the old opera houses survive in the twenty-first century.

In the United States, as the country moved westward in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the growth of railroads brought people to small towns and rural areas. The railroad would also prove useful in transporting entertainment troupes on tour across the country. Small-town boosters began constructing opera houses with elaborate façades and luxurious interiors to show the world that their community was civilized. Like those in other small towns across America, opera houses in Arkansas also functioned as community spaces for graduation ceremonies, school plays, political debates, and public meetings, as well as a place for civic groups to meet, all of which reinforced community pride. As rail travel expanded in Arkansas, local opera houses attracted celebrities of the day. However, many opera houses fell victim to fires in which records were destroyed, so in most cases, it is difficult to determine exactly who performed in Arkansas.

Most opera houses were constructed in the downtown business district as part of buildings with two or more stories, with the lower level usually occupied by retail shops. The interiors were as sumptuous as the owners could afford. The exterior was commonly an elaborate mix of Classical Revival, Italianate, and Victorian architecture. Most had the words “Opera House” with the name of the town carved in stone at the top of the exterior façade as a point of pride until being destroyed in later years as the buildings were demolished.

One community—Van Buren (Crawford County)—has kept its century-and-a-quarter-old King Opera House on Main Street alive as a performance space and venue for community events. Constructed in 1891, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. During its original incarnation, the ground floor was home to a billiards parlor, restaurant, and saloon, with the Van Buren Press newspaper on the second floor. The King Opera House was purchased from its original owners in 1898 by Colonel Henry P. King. According to the local newspaper in 1901, King sought to renovate the property in order to provide an up-to-date facility for the town. During this era, the King Opera House was home to Chautauqua programs, lectures, musicians, preachers, vaudeville acts, and local performance groups. In 1914, a fire gutted the building. The King Opera House was remodeled, reopening as a “moving picture” house. In 1919, it was renamed the Van Buren Theater, continuing its life as a movie house. During the 1930s, in honor of Bob Burns, a local celebrity who was a nationally known radio and film personality of the era, the building was renamed the Bob Burns Theater. The first floor still housed small shops, with an upstairs residential space used as an apartment for the projectionist’s family. In the 1960s, the Bob Burns Theater was purchased by Malco Theaters, but it was closed in 1974. Five years later, the property was purchased by the City of Van Buren, which rehabilitated, renovated, and structurally enhanced the building. It is again called the King Opera House in the twenty-first century, and the interior retains some of its original features along with those that reflect what an average small-town opera house might have looked like. The restored King Opera House is operated by Arts on Main, a local non-profit organization. It is used for performances and special programs as well as being available for rental.

Other opera houses did not fare as well. For example, in 1906, the Knights of Pythias Lodge in Fayetteville (Washington County) organized financing for construction of a theater, to be known as the Knights of Pythias Hall and Opera House. By 1907, the first moving pictures were being shown in Fayetteville, and the venue was eventually renamed the Ozark Theater, remaining as a movie house into the 1980s. After the auditorium was demolished, the building was remodeled and put to other uses, such as office space. Some of the original building’s front wall remains at College and Center streets in downtown Fayetteville.

The three-story Grand Opera House was constructed in Helena (Phillips County) in 1887, seating about a thousand people. As with many other opera houses, there were retail storefronts on the ground floor. The building stood on Porter Street west of Cherry, where Helena’s Court Square Park was later established. The first performance when Helena’s opera house opened in early 1888 was by actress Patti Rosa, one of the most popular touring entertainers in America at the time. That same year, Helena joined a consortium called the Arkansas Theatrical Circuit, which consisted of opera houses at Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Hot Springs (Garland County), Little Rock (Pulaski County), and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in order to bring touring shows to the state. In its heyday, Helena’s opera house was the town’s cultural center, hosting well-known acts as well as local events. In 1926, a fire destroyed the building and most of its records. A historical marker on the site where it once stood carries the inscription: “Traveling road shows, vaudeville, dog-and-pony shows, mind readers, magicians, bell ringers and boxing matches—they all appeared live at Helena’s Grand Opera House.”

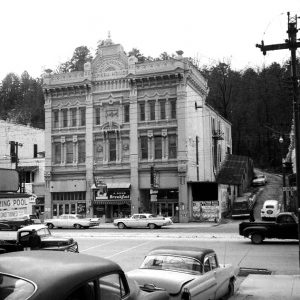

With affluent visitors coming to Hot Springs from around the nation to seek health benefits from the town’s thermal waters, the Hot Springs Opera House opened in 1882 after being financed by civic leader Samuel Fordyce. Entrepreneurs believed that people wanted entertainment, not only locals but also out-of-towners after a day of soaking in the baths. An early theater had been housed above the fire station, where it was not uncommon for performances to be interrupted by the clamor of the fire alarm. Such disruptions played a part in the creation of the new opera house. The three-story brick building stood downtown at 200 Central Avenue, on the city’s main thoroughfare. According to the Garland County Historical Society, it was called the “finest example of Victorian opera house architecture between the East Coast and Central City, Colorado.” With its red velvet curtains and frosted gas lights, it could host about a thousand patrons in its auditorium, balcony, and four opera boxes. The building had businesses on the ground level, including an undertaker at one point. A unique feature of the Hot Springs Opera House was that audiences entered an elaborate third-floor lobby from Canyon Street on the side of the mountain at the rear of the building. The Hot Springs Opera House attracted popular acting companies, performers, singers, and musicians as well as speakers such as the nationally known William Jennings Bryan. Acclaimed actress Lillian Russell appeared there, as well as the notorious Evelyn Nesbit (known as “The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing”) and melodramatic actor James O’Neill, father of playwright Eugene O’Neill. There were often parades down Central Avenue to announce the opening of a new show, including one in 1882 for General Tom Thumb of P. T. Barnum’s circus. Local events were also held at the opera house, with the first Hot Springs High School graduation ceremony taking place there in 1886. A turning point for the Hot Springs Opera House occurred in 1904, when a large new performance venue in town called the Auditorium Theater began to attract the major events. The opera house was left with minor vaudeville acts, although in 1911 there was an attempt to show motion pictures there. The final live performance was a minstrel show in late 1917. The space then stood empty, although businesses continued to operate on the ground level through the 1950s when the building was condemned by the city. A fundraising attempt to save the old Hot Springs Opera House was not successful. It was torn down in 1961, with the space becoming a multi-level parking deck.

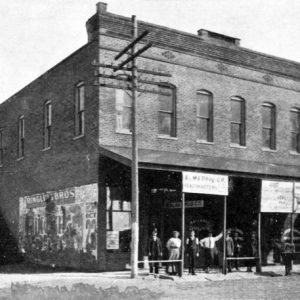

A few Arkansas opera houses remained through the years, although usually in an altered state. Located at Walnut and First streets in Rogers (Benton County), the original two-story Rogers Opera House dates back to the 1890s. It gave its name to a popular downtown business area that was called the “Opera Block” where there were several stores at street level. The Rogers Opera House attracted touring productions, lectures, minstrel shows, musical performances, political debates, school plays, wrestling matches, and even the town’s annual Fireman’s Ball as a fundraiser. During a renovation in later years, a poster was found promoting an appearance by Sitting Bull, along with a report that Thomas Edison also spoke there. Around 1903, the building was remodeled to add another story, a dressing room, and a balcony accommodating about 650 people. However, after the building’s peak year of usage in 1917, motion pictures were luring audiences to other venues in town. By the 1930s, the Rogers Opera House was vacant, with its windows bricked in and some of its furnishings being sold. The building’s structure still stands in the twenty-first century, with long-term attempts being made at restoration work.

In the downtown commercial district at Wynne (Cross County), the two-story brick building of the Wynne Opera House stood until 2024. Constructed in about 1900, the building was home to a performance space above businesses on the first floor. By 2013, the Wynne Opera House building was classified as endangered by the Preserve Arkansas organization. One of its significant features was the presence of painted “ghost signs,” fading decades-old advertisements on an exterior side wall. According to Preserve Arkansas, the building retained a lot of its historic character and integrity. However, the deteriorating building was demolished in 2024, having earlier suffered extensive storm damage.

Other opera houses in Arkansas followed much the same trajectory as those spotlighted here, enjoying their heyday during the late 1800s and early 1900s in bustling downtown districts until the buildings faced demolition in years to come. For example, the Grand Opera House in Fort Smith opened in 1887 and stood downtown on Garrison Avenue, a main thoroughfare in the city’s historic business district. The 400-seat Jonesboro Opera House in Jonesboro (Craighead County) was opened in 1894 but was closed in 1895 when a larger theater downtown was built nearby. In Little Rock, the Kempner Theater on South Louisiana Street was built in 1910 by the founders of Kempner’s department stores. Originally designed to be an opera house, it became a movie house after several renovations in the 1920s and was re-named the Arkansas Theater. When it closed in 1977, it was the last theater remaining in downtown Little Rock. After almost twenty years of sitting vacant and deteriorating beyond repair, the structure was razed in 1995, with the land repurposed as a parking lot.

For additional information:

Adams, Betty. “Small Town was Home to Venerable Opera House.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 2, 2008. https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2008/jan/02/small-town-was-home-venerable-opera-house-20080102/ (accessed April 21, 2025).

Droessler, William F. “Ten Nights in a Bar Room and Other Melodramatic Fare; or, Monticello’s Opera House.” Drew County Historical Journal 15 (2000): 40–49.

Early, Katherine Gee. “Camden’s Opera House.” Ouachita County Historical Quarterly 35 (Summer 2004): 9–11.

Hales, James. “Remembering Rogers: Opera House Brought Back to Life in Ongoing Restoration.” Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 26, 2020. https://www.nwaonline.com/news/2020/mar/26/james-hales-opera-house-brought-back-to/ (accessed April 21, 2025).

Hanley, Ray, and Steven Hanley. Hot Springs, Arkansas. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

Heard, Kenneth. “Digs of the Deal: From Vaudeville to Ghosts, Van Buren’s Opera House Has Seen It All.” AMP Arkansas Money and Politics, January 23, 2024. https://armoneyandpolitics.com/van-buren-opera-house/ (accessed April 21, 2025).

“History Tuesday: The Helena Grand Opera House.” Delta Cultural Center, August 3, 2021. https://www.facebook.com/DeltaCulturalCenter/posts/history-tuesday-the-helena-grand-opera-houseopera-houses-were-not-only-places-of/10160001141663643/ (accessed April 21, 2025).

“Kempner Heirs Give Opera House for Use by UALR, Art Groups.” Arkansas Gazette, May 22, 1980, pp. 1A, 3A.

King Opera House. https://kingoperahouse.com/ (accessed April 21, 2025).

“King Opera House.” City of Van Buren. https://www.vanburencity.org/228/King-Opera-House. (accessed April 21, 2025).

“Live at the Opera House (Helena).” Historical Marker Database. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=107996 (accessed April 21, 2025).

Moore, Garrett. “Rogers Opera House Restoration on the Way, Owner Says; Downtown Businesses Concerned About Safety, Appearance.” Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 5, 2023. https://www.nwaonline.com/news/2023/feb/05/rogers-nwopera-house-restoration-on-the-way-owner/ (accessed April 21, 2025).

“Opera House Burns.” Phillips County Historical Review 33 (Spring 1995): 33–37.

Robbins, Elizabeth. “Time Tour: The Opera House.” Hot Springs Sentinel-Record, June 1, 2021. https://www.hotsr.com/news/2021/jun/01/time-tour-opera-house/ (accessed April 21, 2025).

Satterthwaite, Ann. Local Glories: Opera Houses on Main Street, Where Art and Community Meet. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Swanda, Michael. “The Rogers Opera House: A Condensation of History.” Benton County Pioneer 24 (Fall 1978): 96–99.

“Wynne Opera House.” Preserve Arkansas. https://preservearkansas.org/wynne-opera-house/ (accessed April 21, 2025).

Nancy Hendricks

Garland County Historical Society

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.