calsfoundation@cals.org

Newspapers during the Civil War

When the Civil War began in 1861, Arkansas was still basically a frontier state, with thirty to forty small newspapers; only about ten remained by 1862. By the end of the war in 1865, only one of those newspapers, the Washington Telegraph in Hempstead County, had published throughout the conflict. The Arkansas State Gazette suspended publication in 1863 but restarted in May 1865.

Arkansas’s newspapers were weeklies with small staffs—primarily just editors and printers. The papers were highly partisan, poorly documented, and had little fresh news from the outside world. The papers got much of their outside news through exchanges, in which editors mailed free copies of their papers to each other. The editors then selected news items from these papers that they thought might interest own their readers and reprinted them, crediting the original publications. Thus, information could be weeks old by the time it got to readers.

Because of the newspapers’ small staffs, one of the war’s first consequences was the shuttering of most papers when their editors and printers enlisted in the military. By mid-1862, the number of newspapers had dropped to about ten, scattered around the state in such towns as Camden (Ouachita County), Helena (Phillips County), Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Little Rock (Pulaski County), and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County).

Newspaper publishers soon faced a quandary: War news increased the number of people wanting a paper, but newsprint was precious. Arkansas had no paper mills, and hauling in paper became increasingly difficult and expensive. In mid-1861, the state’s premier newspaper, the Arkansas State Gazette (originally the Arkansas Gazette), dropped subscribers who were two years behind on their payments. Later that year, the Gazette announced cash-only subscription rates of $2 a year in coins or $2.50 in paper money. The Gazette’s capital city competitor, the True Democrat, took similar measures.

Another consequence of the war was the mail service’s collapse. Outside newspapers became so scarce that, in 1863, True Democrat editor Richard H. Johnson offered free subscriptions to anyone furnishing papers from east of the Mississippi River. That same year, the True Democrat’s newsprint situation became so dire that it printed its July 8 edition (which was its last) on brown wrapping paper.

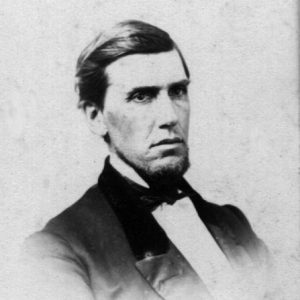

The Washington Telegraph had depended on a Nashville, Tennessee, mill for its newsprint. In March 1862, Telegraph editor John R. Eakin told readers that the mill was in enemy hands. The Telegraph reduced each edition’s size from four to two pages (known as a half-sheet) and began printing only for paying customers. By going to two pages, the newspaper could continue to print for a year, Eakin said. Fortunately for the Telegraph, when its supply ran out, the Confederate military had begun furnishing newsprint.

The Gazette was forced to suspend publication after Union forces captured Little Rock on September 10, 1863. Typically, when Union troops captured communities, they would shut down the newspapers and start new ones supporting the Union. The National Union published one issue from the Gazette offices, but apparently its tone was too conciliatory for one of the Union generals in Little Rock; it lasted only one edition. A second Unionist paper, the National Democrat, began publishing soon afterward. It continued to publish until May 1865.

A third Unionist paper that sprang up in Little Rock was the Unconditional Union. In 1864, Lieutenant Governor Calvin Comins Bliss, who had moved from New England to Arkansas in 1854, bought an interest in the dormant True Democrat and began publishing the Unconditional Union. Bliss would continue to publish the newspaper until 1866 when, while he was in Washington DC on state business, there was a fire at the newspaper. Bliss suspected arson.

At Fort Smith, which Federal forces occupied on September 1, 1863, the Fort Smith New Era began publication that fall. Because of the paper scarcity, the first issue was printed on the back of fliers printed with President George Washington’s farewell address to the U.S. Congress. The fliers had been made two years earlier and handed out by Fort Smith Unionists to try to counter secession efforts.

“E Pluribus Unum” was listed as the New Era’s editor. In a greeting to readers, the editor stated that the area needed a paper to stand up for “the rights of the many against the encroachments of the few…[and that] a number of loyal citizens have determined to supply this grievous deficiency.” The newspaper’s name came from the idea that “a new era is indeed dawning upon the People, [and] will be conducted upon the ‘Unconditional Union’ principle. Traitors, and sympathizers with such, will be exposed unflinchingly.” Newspapers devoted to the Confederacy had imposed upon Fort Smith and other places, the editor stated. “But the tables are turned now, and the freedom of the Press and of Speech will no longer be a dead letter.”

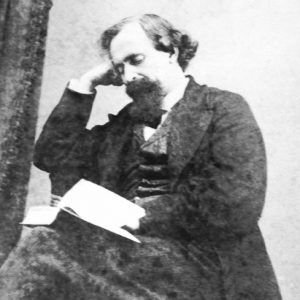

In the next issue, Valentine Dell was listed as the New Era’s editor. Originally from Germany, Dell had settled in Fort Smith in 1859 and had opened a school, the Fort Smith Male and Female Seminary, where he taught until he founded the newspaper. After the New Era’s first edition, military authorities at Fort Smith ensured that Dell had sufficient newsprint to continue publishing.

With the Federal occupation of Little Rock, Fort Smith, and other communities along the Arkansas River, southwestern Arkansas became the last Confederate stronghold in the state. It would remain so until the end of the war. Arkansas’s Confederate capital was re-established at the southwestern Arkansas town of Washington (Hempstead County), which had been a thriving antebellum community.

The Telegraph’s Eakin, a Tennessee-born lawyer, saw his newspaper’s duties as buoying public morale and unifying citizens behind the Confederate cause. He believed order was essential to society, and that meant preserving the South’s social and economic structure. In a front-page editorial in 1864, Eakin wrote of President Abraham Lincoln: “Amongst those stupendous wrongs against humanity, shocking to the moral sense of the world…the crime of Lincoln in seducing our slaves into the ranks of the army will occupy a prominent position.”

After the war, Eakin served two years in the state legislature, was part of the convention that drafted Arkansas’s present-day Constitution, and served as an Arkansas Supreme Court justice from 1878 until his death in 1885. The Telegraph published until 1946.

With the Civil War nearly over, Gazette owners Christopher Columbus Danley and William Frederick Holtzman began working to resurrect their newspaper. Both had taken an oath of allegiance to the United States. On Wednesday, May 10, 1865, they began publishing a Monday–Friday daily. They began publishing a Saturday weekly on May 13. The Gazette, which came to tout itself as the oldest newspaper west of the Mississippi, continued publishing until 1991.

For additional information:

Dougan, Michael B. Community Diaries: Arkansas Newspapering, 1819–2002. Little Rock: August House, 2003.

Rhodes, Sonny. “Opposite Extremes: How Two Editors Portrayed a Civil War Atrocity.” American Journalism 22 (Fall 2005): 27–45.

———. “Tussling in Type.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 8, 2024, pp. 1D, 6D. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/jan/07/history-underfoot-rivaling-little-rock-papers/ (accessed November 26, 2025).

Ross, Margaret. Arkansas Gazette: The Early Years, 1819–1866. Little Rock: Arkansas Gazette Foundation, 1969.

Smith, Robert Freeman. “John R. Eakin: Confederate Propagandist.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 12 (Winter 1953): 316–326.

Sonny Rhodes

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.