calsfoundation@cals.org

Newark (Independence County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º42’06″N 091º26’29″W |

| Elevation: | 239 feet |

| Area: | 1.64 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 1,180 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | April 12, 1889 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

115 |

315 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

595 |

906 |

897 |

802 |

913 |

728 |

849 |

1,128 |

1,159 |

1,219 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,176 |

1,180 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Throughout much of its history, Newark has been one of Independence County’s larger towns. Called by the local newspaper the “Queen City of South Independence” in the early 1900s, the town held great promise to be a significant part of the history of the county. Like most small towns in early twentieth-century Arkansas, its early years were full of hope and prosperity, but it later suffered the loss of its business community and a significant part of its populace.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

Newark was founded as an alternate site to an older town plagued with a major drawback. The pre–Civil War community of Akron (also known as Big Bottom) was subject to the destructive overflows of the White River. In 1880, plans for a proposed railroad would have had it passing through Akron, but the revised 1882 plans sought higher ground on which to lay tracks about a mile north. As a result, one town’s shortcomings led to the founding of another.

Town founder John N. Tomlinson’s house was on a rise overlooking the bottoms. It had been a landmark since the mid-1850s. In1883, he laid out the town, named it, and began promoting it. Tomlinson became the town’s first postmaster on June 5, 1883. No one is sure how he came up with the name Newark. Some say it was a version of “New Akron,” while others claim Tomlinson was like the biblical Noah and that the town was his “New Ark” to save residents from flooding. It might have been simply a new town in Arkansas, hence “New Ark.”

In 1882, the Iron Mountain and Southern Railroad included part of Tomlinson’s land in its survey. The first train to pass by Newark on the railroad’s Batesville branch was in March 1883. The town depended heavily on the railroad to transport people and goods. People rode on passenger trains like the “Hot Shot.” Local travelers rode the well-known “Bull Moose” motorcar, a 1912 gas-electric motorcar that began service in 1924.

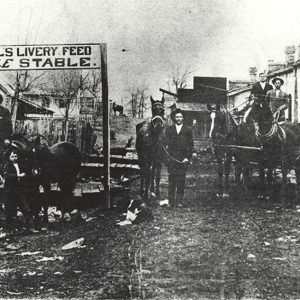

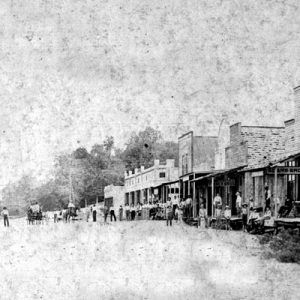

An incorporation petition for the town was filed with the county court on January 7, 1889, and it was officially recorded on March 23. The first businesses were founded around the time the railroad opened. Individual mercantile operations owned by Jimerson Moore, John Tomlinson (his was also known as the “Big Store”), Thomas Clark, and J. H. Murphy were the first retail establishements of the town. The depot was probably the first non-mercantile business constructed. The main hub of business was Front Street, which faced the tracks on its north side. The town grew quickly, and the stores were patronized not only by Newark residents but by those from Magness, Paroquet, Oil Trough, and other Independence County neighborhoods.

Early Twentieth Century

In the early years of the twentieth century, a large number of African-American citizens called Newark and its surrounding region home. Most of these families were descended from the slaves who worked the ground in the years before the Civil War. The white and black communities coexisted together through the years very well with few racial problems, though the town was racially segregated. The school for African Americans was open until the 1930s, when those students were bused to Batesville for their education. Today there are only a couple of African-American families who live in Newark.

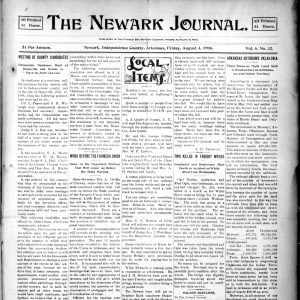

The town was active in community and political affairs in the early years. It was a staunch Democratic town, but a few Republicans were scattered throughout. Although the town was not large, political rallies and community picnics drew people from far and wide, and many times they featured prominent state politicians. Arkansas Governor Jeff Davis campaigned in the town in 1904 and verbally abused the editor of the local newspaper, the Newark Journal. Oscar F. Craig, who published the aforementioned newspaper, attempted to retaliate physically, but his friends held him back, and Davis quickly left town. In the election following that incident, the popular Davis lost Newark by a factor of two-to-one.

Newark survived the years of the Great Depression with some moderate success. Newarkers who lived during time were accustomed to living without many of the niceties to which others had grown accustomed. Local mercantiles granted credit to many who were depending on it to simply survive. Also, Works Progress Administration (WPA) projects helped give jobs to many local citizens.

World War II through the Modern Era

Newark has sent men—and some women—to every war since its founding. Nearly 400 men and women from the area were in the service during World War II, and nineteen of those men died. World War II had another lasting impact on Newark. Many families moved out of state to work in aircraft and other war-related industrial plants. Most of these people established lives and careers elsewhere and never returned to live in Newark permanently.

The 1950s and 1960s were not the town’s best years. The population dropped to 723 in 1960, its lowest number since before 1920. Its fifty-eight-year-old newspaper, the Newark Journal, shut down. In early 1960, after seventy-seven years of passenger rail service, rail transportation was no longer available.

A downtown revival in the 1980s resulted in the restoration of several old buildings, which were occupied by unique businesses. Antique and gift shops, an old-fashioned soda fountain, and a lamp factory are all part of the town today.

The town sponsors a festival at the end of every summer. The “Times and Traditions” festival, also known as “TNT,” has featured short train excursions and entertainment. First presented in 1995, the festival draws many people back to the town, some who have long-established family ties to the area.

Oddly enough, Newark’s population in 2000 of 1,219 was the largest recorded in the town’s history, although the number of local businesses is probably at an all-time low. In the fall of 2003, the Highway 69 bypass of Newark was complete, thus allowing one to drive from Newport (Jackson County) to Batesville (Independence County), missing Newark altogether. By the 2010 census, the population had declined slightly, to 1,176.

Industry

Newark has contributed to the state’s growth mostly through agriculture. For more than 100 years, producers primarily grew cotton. In the 1960s, rice and other grains became more profitable to grow. Cattle operations have also been successful. A number of poultry-raising operations have been established around Newark, and their flocks are taken to Batesville for processing.

Although several small industries operated in the city in the early years, none was of major concern. Today, the town boasts one of the state’s largest electric steam generating plants. In 1983 and 1984, the $525.9 million Independence Steam Electric Station began generating power from low sulfur coal. It serves several surrounding states.

Education

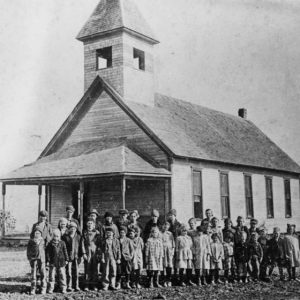

Newark has had a public school system at least since 1885. It was into this system that as many as thirty rural schools were consolidated beginning in the late 1940s. The town’s $6.8 million campus was built in 1984 from taxes generated from the electric plant. The school has found itself now in a situation of having to support a large complex with less tax revenue coming in. In 2004, Newark was consolidated with the Cord-Charlotte School District to create the Cedar Ridge School District.

Attractions and Famous Residents

The community features three sites on the National Register of Historic Places. The Dearing House, originally constructed around 1890 in Akron, represents the movement of people from river areas to places where rail served. It was moved to Newark in 1901. The Akron Cemetery, originally a Native American burial ground, contains graves of white people dating from the 1840s. The last overhead-truss steel bridge in Independence County, built in 1909, is west of the Akron Cemetery.

Newark has laid claim to a couple of firsts and seconds in Arkansas. Its extensive 1910 sidewalk improvement project was perhaps the first bond project of resident Thomas J. Raney, who later moved to Little Rock and founded the investment firm T. J. Raney & Sons. The firm is still in business. Dan C. Moore established the state’s second radio station, KGCG, in the Moore Motor Co. in September 1926. Koleta’s Kurio Kabin was an almost-forgotten 1930s museum that housed the collection of Koleta Walker, who grew up in nearby Sulphur Rock (Independence County) and, with the help of her great uncle Warfield Sanders, built the museum just west of Newark. It displayed artifacts and relics from all over the world and included a gun and Native- American collection. In 1935, she acquired a piece of fabric from Wiley Post’s original Winnie Mae, the Lockheed Vega aircraft in which he made two trips around the globe. However, the museum had closed by 1939.

Singing movie star Tex Ritter made Newark a favorite stop on his tours. The Royal Theater played so many of his movies that he visited the town and returned several times after getting to know some of the people. Ritter dedicated the song “It Makes No Difference Now” from his 1939 movie Down the Wyoming Trail to the women of Newark.

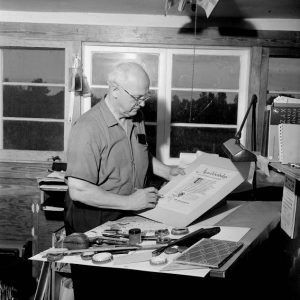

In 1951, Raymond F. Daboll, who has been called America’s greatest calligrapher, moved to Newark. He was a contemporary of many of the country’s great illustrators and graphic artists. Designers and executives from Chicago, Illinois, and New York, New York, found their way to Newark to work on projects that were distributed nationwide.

For additional information:

Craig, Robert D. A History of Newark, Arkansas: The Story of a Town, the Personality of a People. Newport, AR: Craig Printing Company, 1999.

Edwards, E.C., and A.C. McGinnis. “Recollections From Newark.” Independence County Chronicle 6 (October 1964): 11–14.

Stockard, Sallie. History of Lawrence, Jackson, Independence and Stone Counties of the Third Judicial District of Arkansas. Newport, AR: Morgan Books, 1986.

Robert D. Craig

Kennett, Missouri

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.