calsfoundation@cals.org

Napoleon (Desha County)

The town Napoleon of Desha County was located at the confluence of the Mississippi River and the Arkansas River. Although its founders had hoped that its location would make it a major city comparable to St. Louis, Missouri, or New Orleans, Louisiana, the town was badly damaged during the Civil War and then totally destroyed within ten years of the war by the flooding of the rivers.

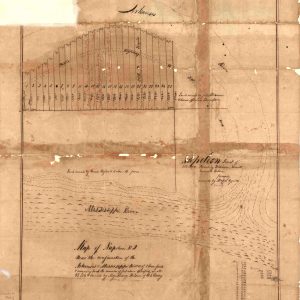

Jacques Marquette visited the area where these two rivers meet in 1673. The area may also contain the burial location of Pierre Laclede Liguest, the founder of St. Louis, who died and was buried on a trip north from New Orleans in 1778. The town was not established, though, until the time of Frederick Notrebe, a wealthy merchant who recognized the potential of the site and who also suggested that the town be named for the late French emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte. Notrebe’s business partner Stephen van Rennsaler Ryan—also a retired soldier—purchased a warehouse and 100 acres of land at the meeting of the rivers, renting them to Jonas Mapes of New York City. The Arkansas Gazette in 1835 advertised the Mapes, Ryan, and Co. warehouse and hotel as connected by a “good road” to Arkansas Post (Arkansas County). The Napoleon post office was established in 1837, and in 1839, the Second General Assembly of Arkansas chartered the Napoleon and Little Rock Railroad.

The crowning achievement of the young community, however, was being chosen as the location for a marine hospital to serve sick or injured boatmen, established and funded by the federal government. The first such marine hospitals had been built in Boston in 1799 and in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1801. In 1837, the surgeon general was authorized to select seven sites farther west for similar hospitals: three along the Ohio River, three along the Mississippi River, and one on the shore of the Great Lakes. His choice was to reflect the healthfulness of the region, its resources for healthcare providers, and its accessibility to boatmen. Napoleon was selected, probably largely for the third qualification. By 1844, Stephen Ryan had sold land to the federal government for a hospital, although problems with the deed to the land existed as late as 1848. In 1850, army officer Stephen Harriman Long was assigned the task of building the hospital in Napoleon. Long objected, pointing out that the location was in frequent danger of flooding, but he was overruled by the U.S. Congress, due to the influence of Arkansas’s senator Solon Borland. In April and May 1850, the construction site was flooded. In fact, weather and other delays prevented the hospital from being finished before August 1854, and it likely did not receive its first patient until the following year.

Meanwhile, the town continued to grow and prosper. Some estimates measure the peak population of Napoleon at 2,000, but census records from 1850 and 1860 suggest a metropolitan population less than half that number. Among the citizens registered were carpenters, doctors, grocers, merchants, attorneys, and workers on the river. Businesses that served the town included coffeehouses, bars, hotels, and restaurants. Farm owners registered a total of 310 slaves for the area in 1860, eighty-four of which lived in town and worked in the houses of planters who also maintained city dwellings.

According to records of the time, Napoleon was notorious as a rough and rowdy town. Edward King, in his 1875 account The Great South, described Napoleon thusly: “Murder daily was the rule, and not the exception. Brawls always ended in burials.” Supreme Court Justice Peter Daniel, who spent a few days in Napoleon waiting for the mail boat to take him to Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1851, called it a “most wretched” place consisting of “a few slightly built wood houses, hastily erected no doubt under some scheme of speculation, and which are tumbling down without ever having been finished.” He also complained of persistent “muschetos” and of “the Buffalo Gnat, an insect so fierce & so insatiate, that it kills the horses & mules, bleeding them to death.” Mark Twain, remembering Napoleon in his memoir Life on the Mississippi (1883), mentioned it as a “town of innumerable fights—an inquest every day; town where I used to know the prettiest girl…and the most accomplished in the whole Mississippi Valley.”

Twain, according to his memoir, was surprised to learn that Napoleon no longer existed where he remembered it. On February 12, 1861, even before Arkansas had voted to secede from the Union, Governor Henry Massie Rector had state troops seize the marine hospital and any ammunition shipments in Napoleon to prevent them from falling into Union hands. By September 1862, Union troops occupied Napoleon, and most of its citizens had abandoned the town. In January 1863, Union soldiers destroyed the county courthouse in Napoleon, using its wood to fuel their fires in the midst of a blizzard.

Meanwhile, Confederate guerrillas were using the wooded peninsula east of the town as a base to attack Union boats. The main channel of the Mississippi River swung east and then west along what was called the Beulah Bend. The turning was so abrupt that the guerrillas were able to use the same cannon to fire on boats as they entered the bend and again when they left it. Lieutenant Commander Thomas O. Selfridge, seeking a way to avoid this ambush point, had the men under his command dig a channel across the peninsula. The work took only a day, since the land was soft, the distance only a few hundred yards, and the current of the river itself assisted their work. In fact, on the day after the work was completed—in the first week of April 1863—Selfridge was able to pilot his steamship, the USS Conestoga, through the new channel. The following month, a Union expedition ventured very close to Napoleon while travelling the Mississippi River.

Although Selfridge was only seeking a shortcut around the guerrilla ambush, he succeeded in rerouting the Mississippi River, ultimately turning Beulah Bend into an oxbow lake. His work also spelled the end of the town of Napoleon, for the new channel of the river happened to be aimed directly at the town. High water in 1868 caused the marine hospital to crumble into the river. Another flood in 1874 completely submerged what was left of Napoleon. By October of that year, the county government was moved to Watson. The iron church bell once used in Napoleon is now in the Catholic church in McGehee (Desha County). At times when the level of the Mississippi is unusually low—as it was in the summer of 1954—the remains of the town can still be detected in the sandbars of the river.

For additional information:

Gould, Mitch, “Death Comes For Napoleon.” Programs of the Desha County Historical Society 13 (Spring 1987): 46–55.

Hammond, Michael D. “Arkansas Atlantis: The Lost Town of Napoleon.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Autumn 2006): 201–223.

“Minister’s Visit to Napoleon in 1843.” Grand Prairie Historical Bulletin 63 (April 2020): 28–30.

“Napoleon Cutoff in Desha County.” Programs of the Desha County Historical Society 12 (Spring 1986): 23–26.

Wood, Richard G. “The Marine Hospital at Napoleon.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 14 (Spring 1955): 38–42.

Steven Teske

North Little Rock, Arkansas

From the diary of Platt Armstrong, 26th Iowa Infantry, after the battle of Arkansas Post beginning January 15, 1863: Jan the 15 “It commenced raining last night and is raining yet. It is very disagreeable weather. ” Jan the 16 “This morning we are all covered with snow and yet it snows. We suffer today. Today the boat has started down the river. 3 o’clock we have stopped to go ashore and kill some beef. We have got 5 and we go still in the night.” January the 17 “This morning the weather is cold and clear and we lay at Napoleon with 4,000 new recruits. The town is deserted and the boys is tearing up everything they can. Beef cattle and sheep is coming in (from) every direction. Here is a marine hospital belonging to the north. It is the only building of note here. It is a town situated at the mouth of the Arkansas River.” Sunday Jan the 18 “This morning quite pleasant but cool. Here we are yet at the mouth of the Arkansas River. The water is rising. I have got the bowel complaint this morning.” Platt Armstrong was my mother’s great-grandfather. My mother and her cousin transcribed Platt Armstrong’s diary. The original handwritten diary is presently the property of the Lakes United Methodist Church in Lake View, Iowa. I edited this excerpt from the transcription by correcting the spelling and adding punctuation. I was searching for information about Napoleon, which Platt spelled “Napalion,” and was fascinated by the verification of the town being used as firewood during the snowstorm.

During the Civil War, it was typical for certain ideas to arise–be it the Battle of the Crater or a diversion channel. Grant used the idea of a channel near Lake Providence, Louisiana, to mitigate problems happening in Vicksburg, Mississippi. I think it was abandoned, and at least the Confederacy still had the town since it wasn’t washed out from Union efforts.