calsfoundation@cals.org

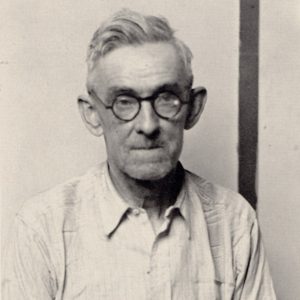

Mike Disfarmer (1882–1959)

aka: Mike Meyer

A portrait photographer in Heber Springs (Cleburne County), Mike Disfarmer’s invaluable contribution to photography and the documentation of rural America went unnoticed until 1973, fourteen years after his death. This eccentric man’s work, which later garnered national attention, captures with stark realism the people in and around Heber Springs in the early to mid-1900s.

The particularities of Disfarmer’s biography are sketchy, largely because of his reclusive lifestyle and meager status during his lifetime. Various sources date his birth to German immigrants as either 1882 or 1884; however, a World War II draft registration card for one “Mike Disfarmer” of Heber Springs lists an August 16, 1882, birth in Daviess, Indiana. Disfarmer’s family later moved to the German community of Stuttgart (Arkansas County). His father, a Civil War veteran, took up rice farming. Sometime after his father’s death, Disfarmer, his mother, and his siblings moved to Heber Springs. Soon after, he entered a partnership with another photographer. He lived with his mother until a tornado destroyed their home in 1926. He then built a studio with living quarters, where he lived and worked until his death.

As a photographer for more than forty years, Disfarmer occasionally was mentioned in the local newspaper, which offered insight into his personality and behavior. He highlighted his desire for individuality in the community by featuring his name change in the newspaper. He was born Mike Meyer, and meier means “dairy farmer” in German; his new name, Disfarmer, is thought to have signified a rebellion against his rural surroundings and his family. He claimed he had been delivered on his parents’ doorstep via tornado. Recollections of the man often cite a bohemian outlook, both gruff and kind. Reclusive and eccentric, the acknowledged town photographer never married and dedicated himself to his work.

Disfarmer earned a meager living off the country farmers and ordinary people. He charged twenty-five to fifty cents for the portraits—commonly referred to as “penny portraits”—that were intended as tokens to be given to family and friends. This strategy provided a wealth of subjects. He occasionally ventured outside the studio, though it seems none of those images survives.

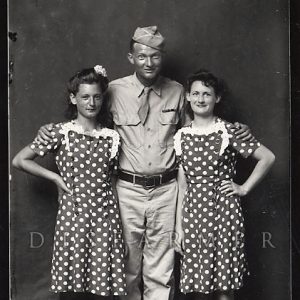

Disfarmer’s approach was simple. Though he used some props in his early photographs, the settings became more and more bare as his work evolved. Stark realism characterizes these portraits. His subjects, sometimes an individual, sometimes groups or families, were rarely captured smiling or interacting. Instead, they have a natural, often solemn expression, never coerced. The sitters are often in their Sunday best, though sometimes they look as though they have just left the fields. Disfarmer’s photographs can be mistaken for those taken by artists and government photographers during the Depression to document the American human condition, but his images are not intended to be among those. Instead, many have noticed his unfailing ability to capture those sentiments despite the intention that the photographs be “penny portraits.” The result is a collection of images of ordinary rural people that captures the essence of a time, a place, and the people who occupied it.

After several years of declining health, Disfarmer died in his studio in 1959 and was found several days later. Afterward, Joe Allbright, a former Heber Springs mayor, salvaged the surviving glass negatives from which Disfarmer made his prints. He had gained permission to search Disfarmer’s home for any items of value. In 1973, Allbright gave the negatives to Peter Miller, a member of The Group and the editor of The Arkansas Sun, a weekly newspaper in Heber Springs. Miller published images of the works in the newspaper for a year, and he shared prints from the negatives with Modern Photography magazine’s Julia Scully, who encouraged and contributed to a publication of Disfarmer’s prints, Disfarmer: The Heber Springs Portraits, 1939–1946, in 1976 in cooperation with Miller. Miller gave most of the 3,000 glass plate negatives to the Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1976.

In the early twenty-first century, Disfarmer gained national attention with accompanying controversy. Until 2004, the only prints known to exist were those made posthumously from the glass plate negatives. That year, a Heber Springs couple moved to Chicago, Illinois, and sold fifty family portraits taken by Disfarmer to New York collector Michael Mattis. Word spread, and soon other Heber Springs residents sought out Mattis to offer portraits. Simultaneously, the Howard Greenberg Gallery’s Steven Kasher, who already had sold prints from the negatives, was contacted with similar offers. Both men sought out the vintage prints and even hired scouts in the Heber Springs area to uncover these treasures. Two shows featuring the prints ran simultaneously in 2005 in New York, at the Edwynn Houk Gallery and the Steven Kasher Gallery.

Prices at the exhibitions ran $7,500 to $30,000 per photograph and sparked controversy. About 3,400 prints were acquired, though the parties involved declined to say how much was paid for them. Many feel that the sellers, unaware of the value of the photographs, were deceived and possibly given far less than the anticipated value.

In spite of his curious personality and narrow focus, Disfarmer earned an adequate wage taking “penny portraits.” These hauntingly observant photographs have stood the test of time. They convey the spirit of a bygone era and have appeared in exhibitions in the Netherlands, Canada, and France. High valuations have ensured the endurance of the original prints and indicated the rarity of the glass negatives that survive. Disfarmer’s notoriety has offered inspiration to many, including fellow Arkansan Andrew Kilgore and Toba Tucker. A New York Times piece by Philip Gefter accurately describes Disfarmer’s photographs as “American Gothic,” disenchanted and real, portraying a slice of American life in the 1920s through the 1950s with unfailing realism.

The Mike Meyer Disfarmer Gravesite in the Heber Springs Cemetery was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.

A July 2021 article in the New Yorker revealed that a group of descendants of Disfarmer’s siblings, spurred to action by outside collectors and a lawyer, had filed suit to obtain control of the Disfarmer estate, asserting that the copyright for his images properly belonged to them. In May 2022, Cleburne County Circuit Judge Holly Meyer ordered the estate reopened, allowing the matter to be litigated. In May 2023, the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts (previously the Arkansas Arts Center) requested a protective order against discovery from the administrator of the Disfarmer estate. Fred Stewart, Disfarmer’s great-great nephew, filed suit against the museum’s foundation in 2024, alleging that the museum had been illegally profiting off the photographs and negatives donated in 1977, but the parties reached a settlement in January 2026.

For additional information:

Blank, Gil, and Tanya Sheehan. Becoming Disfarmer. Purchase, NY: Neuberger Museum of Art, 2014.

Bowden, Bill. “Disfarmer Copyright Suit Ongoing.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 1, 2025, pp. 1B, 2B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2025/jan/31/disfarmer-negatives-illegally-sold-in-1959/ (accessed February 3, 2025).

———. “Disfarmer Negatives at Center of Dispute.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 18, 2023, pp. 1A, 12A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/jun/18/disfarmer-heir-little-rock-museum-argue-over/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

———. “Disfarmer Kin Sue to Claim Photos.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, November 10, 2024, pp. 1A, 11A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/nov/09/disfarmer-relative-sues-to-claim-late/ (accessed November 11, 2024).

———. “Disfarmer’s Photos Are at Issue in Court Filing.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 16, 2023, pp. 1A, 5A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/may/16/museum-wants-protection-from-disfarmer-discovery/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

———. “Estate Reopened 63 Years after Photographer Died.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 20, 2022, pp. 1A, 7A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/may/20/judge-reopens-estate-case-of-heber-springs/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

———. “Lawyer Insists Copyright Bid Not Applicable.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 24, 2024, pp. 1B, 2B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/dec/23/museum-lawyer-says-disfarmer-heirs-way-late-to/ (accessed December 26, 2024).

———. “Old Negatives Become Focus of Court Dispute.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 18, 2021, pp. 1A, 6A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/jul/18/old-negatives-become-focus-of-court-dispute/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

———. “Order Signed in Disfarmer Case.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 27, 2022, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/may/27/judge-officially-reopens-the-estate-of-mike/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

Davis, Kim O. Disfarmer: Man behind the Camera. N.p.: 2014.

Disfarmer. http://www.disfarmer.com/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

Gefter, Philip. “From a Studio in Arkansas, a Portrait of America.” New York Times. August 22, 2005, pp. 1E, 4E.

Kasher, Steven, ed. Original Disfarmer Photographs. New York: Steven Kasher Gallery, 2005.

Orbey, Eren. “Who Owns Mike Disfarmer’s Photographs?” New Yorker, July 13, 2021. Online at https://www.newyorker.com/news/us-journal/who-owns-mike-disfarmers-photographs (accessed July 11, 2023).

Scully, Julia, and Peter Miller. Disfarmer: The Heber Springs Portraits, 1939–1946. Danbury, NH: Addison House, 1976.

Trachtenberg, Alan, and Toba Tucker. Heber Springs Portraits: Continuity and Change in the World Disfarmer Photographed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

White, Mel. “Mike Disfarmer.” AY Magazine, December 2018, pp. 66–69.

Eileen Turan and Keith Melton

Arkansas Arts Center

I am curious as to why the Arkansas Arts Center in Little Rock displayed (as of 2018) only one photograph of Mike Meyer Disfarmer’s photographs. They were given the 3,000 plus glass negatives of his photographs, so why do they not print them and proudly display at least some of them? His work is an important part of Arkansas’s artistic history.