calsfoundation@cals.org

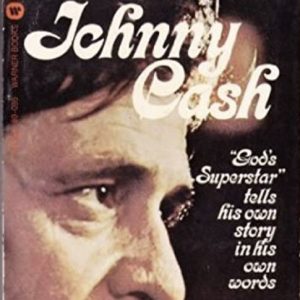

Man in Black [Book]

Man in Black is the first autobiography by Johnny Cash. The bestselling book includes extensive discussion of Cash’s days in Arkansas and focuses on Cash’s recovery from addiction and his closer embrace of Christianity. Published in 1975, it was one of two autobiographies Cash wrote in his lifetime.

By 1975, Johnny Cash was an institution. For twenty years, he had enjoyed immense success as a country star. He had seemingly done it all—made hit records, appeared in movies, and had a nationally televised variety show on ABC. By the mid-1970s, though, Cash’s life and career had settled down, and Cash saw it as time to write his life story.

Toward the end of 1967, Cash had begun to sober up, though the process took several years. In 1968, he married fellow country singer June Carter, who had helped him get clean. Gone were the days of all-night drug binges and the trashing of hotel rooms. In early 1970, he became a father for the last time to his only son, John Carter Cash. For years, he was sober and free of drugs, and in 1971, he became a born-again Christian, an experience documented in the Charles Paul Conn book The New Johnny Cash.

Named after the album and song of the same name from 1971, Man in Black bears the same style of Johnny Cash’s music. It is direct, honest, and rooted in his Arkansas experiences. Cash spends much of the book discussing growing up in Dyess (Mississippi County) as the son of cotton farmers Ray and Carrie Cash. Known then as “J. R.,” Cash was the middle child in a family of seven. He hated working in the cotton fields, but his experiences shaped his later life and career. In Dyess, he listened constantly to the radio, learned spiritual and popular songs, took a few music lessons (but did not become a guitar player yet), and sang in school and in the cotton fields.

Man in Black is concerned with the themes of redemption and recovery from drugs. Cash called it a “spiritual odyssey.” Religion is everywhere in Man in Black. “Jesus Was Our Savior—Cotton Was Our King,” Cash titled one chapter. As the son of a Baptist father and a Methodist mother, Cash had a religious upbringing similar to many southern whites. But he was never a fundamentalist or intolerant of other faiths. His religion stayed with him his entire life, though he would—by his own admission—not always be a good Christian.

Man in Black makes clear how Cash’s rural, blue-collar background informed his songs. Cash might have detested picking cotton, but he later wrote about it in such classics as “Pickin’ Time.” Furthermore, “Country Boy,” recorded with Sam Phillips at Sun Records, was clearly autobiographical. Living in Arkansas affected Cash’s music in unexpected ways, too. Cash recalls that the humming intro to “I Walk the Line,” for example, was based on the sound a Dyess dentist made when Cash visited him.

Perhaps the most poignant moment in the book concerns the death of Cash’s brother Jack in a sawmill accident. Cash had wanted to go fishing with his brother that day, but Jack refused, saying he wanted to make some money cutting wood. Jack, who had wanted to be a preacher, was not only his older brother but a good friend to Cash; the two slept in the same bed. Cash kept Jack’s pillow for the rest of his life (and it is now part of the Johnny Cash Boyhood Home). Jack’s death had a profound effect on the whole family, and Cash carried the trauma of his brother’s death his entire life.

Cash began having drug problems around the time he became famous and was touring constantly. He took amphetamines to stay awake and have energy as a performer. Eventually, though, the pills endangered his life and relationships. In the book, Cash is honest about his addiction, what he calls the “Demon of Deception.” To recover, Cash enlisted the help of June Carter and a Nashville doctor named Nat Winston.

In addition to many early stories about Arkansas, Cash recounts in detail meeting guitarist Bob Wootton for the first time in September 1968 at a political rally for Winthrop Rockefeller. Two members of Cash’s band were unable to make it to the show. A seasoned performer and huge fan of Cash, Wootton had traveled from Oklahoma, and he managed to convince June Carter to let him play with his hero. Cash agreed, and Wootton did so well that he became a member of the touring band for thirty years.

Some Cash fans may be surprised by what is not in the book. In his later 1990s memoir, Cash discusses a supposed suicide attempt he made in Nickajack Cave in Tennessee in 1967. The story, however, is not mentioned in Man in Black. Nor does Cash describe the Flood of 1937, a disaster he had immortalized in his 1959 song “Five Feet High and Rising,” despite the fact that he had talked about the flood on stage for years and in interviews.

Cash had help in writing the book from Peter E. Gilquist, an author and archpriest in the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America. Gilquist also worked at the University of Memphis and the publishing house Thomas Nelson in Nashville. At the time, Nashville was the country music capital and the center for Christian publishing in America. Man in Black was printed in Michigan by Zondervan, a specialist in Christian books.

Cash dedicated Man in Black to his father-in-law, Ezra J. “Eck” Carter. Cash notes that Carter “taught me to love the Word.” Ezra was a religious man as well as something of a fun-loving “good ol’ boy.” He and his wife, Maybelle, had taken care of Cash many times when he was strung out in Nashville. By the 1970s, Cash was making amends for past bad behavior, and he wanted to acknowledge how much Ezra meant to him.

Man in Black was a commercial success, selling more than a million copies. In the mid-1970s, Cash was riding high. The next year, he had his last number-one single, “One Piece at a Time.” Cash, however, was not done as a musician. Nor were the drugs done with him. In his second memoir published in 1997, he would write of his continued battles with addiction and other dark themes.

For additional information:

Cash, Johnny. Man in Black. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1975.

Conn, Charles Paul. The New Johnny Cash. New York: Family Library, 1973.

Hilburn, Robert. Johnny Cash: The Life. New York: Little, Brown, 2013.

Malone, Bill C., ed. The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, Vol 12. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Colin Edward Woodward

Richmond, Virginia

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.