calsfoundation@cals.org

Lovett Davis (Lynching of)

Early on the morning of May 25, 1909, an African-American man named Lovett Davis was hanged in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) for an alleged assault on a young woman named Amy Holmes. Although the Arkansas Gazette reported that Davis was from Atlanta, Georgia, and had relatives there, public records provide no information to confirm this. Amy Holmes was living in Pine Bluff with her uncle, railroad conductor H. Knowlton Padgett. Holmes was the daughter of Knowlton’s older sister, Harriett, who died in Batesville (Independence County) in 1893. She was still living with the Padgetts in 1910.

According to the Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, Davis, described as a “big burly negro,” was a suspect in several robberies in Pine Bluff. Intent on further robbery, he allegedly entered the Padgett home through a window around 4:30 a.m. on Friday, May 21, while H. Knowlton Padgett was away. When he encountered Holmes, he choked her to prevent her from raising the alarm. Although Holmes “was almost prostrated from fright” and could hardly speak because of her injured throat, she managed to scream, attracting the attention of her aunt. Davis escaped through a window, and Harriett Padgett reported the incident to the police. Holmes was not able to identify her attacker, but early Friday evening, the police learned that an African-American man was hiding under a porch in the suburbs east of Pine Bluff. When they arrived at the house with bloodhounds, they discovered that the African-American man who lived there had fired shots at the stranger, who had then run away. They chased Davis with the dogs for two hours but lost him in a lumber yard. The following morning, Davis was seen standing on the street in Pine Bluff, and officers arrested him on suspicion of having been involved in a recent robbery. Davis admitted to the attack on Holmes and said that after he eluded the searchers he spent the night at Sander’s Mill Yard. Davis was then put in jail.

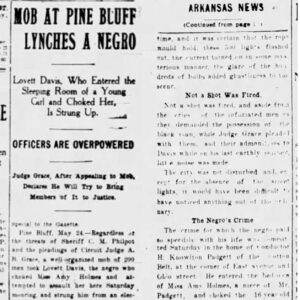

According to the Arkansas Gazette, around midnight on May 24, a mob of about 200 men went to the jail in what appeared to be a well-planned attack. Circuit Judge A. L. Grace was at the jail at the time, as were Sheriff C. M. Philpot and Deputy Sheriff W. L. Goodwin. All three men pleaded with the crowd in an attempt to protect Davis but were overpowered. Grace warned the men, who were not masked, that he recognized some of them and that he would “personally conduct the investigation and see that they were duly punished if the negro was harmed.” Philpot, though armed, did not fire. The Gazette defended his actions, saying that had he not stepped back there would have been “more bloodshed…a battle would have resulted, as the men were all heavily armed and ready for the worst.”

Members of the mob broke down part of the jail wall with sledgehammers, and then broke the door locks. Davis, pleading for his life, was dragged away. For some reason, the town had gone dark, and there were no street lights burning. The members of the mob argued for a time about which pole to hang Davis from but eventually settled on one at Second Avenue and Main Street. On their first attempt to hang Davis, the rope broke, but their second attempt was successful. Interestingly, a large cluster of incandescent lights had been installed at the site, and when Davis was strung up for the second time, they suddenly flared into life, and “the glare of the hundreds of bulbs added ghastliness to the scene.” There were no shots fired, and according to the Gazette, “except for the absence of the street lights, it would have been difficult to have noticed anything out of the ordinary.” Davis’s body was taken to the Holderness Undertaking Company, “where hundreds of negroes called during the day and viewed it. There has been no further disturbance today and the general consensus among the negroes seems to be that Davis received only what he deserved. No further trouble is anticipated between the races.”

On the evening of May 25, Judge Grace announced that he would charge the grand jury to investigate the lynching, and the grand jury convened on May 26 to examine the case. According to the Gazette, the judge delivered a strong charge to the jury. Although he noted that the women of the South lived in fear of being assaulted by “some black brute,” and that the public felt that “the law is not to be depended upon,” they should “not allow their sympathies to blind them to duty” and should uphold the “supremacy of the law.” The Arkansas Democrat reported that although some members of the mob might be indicted, they would probably not be convicted because “public sentiment is in their favor….Pine luff [sic] is in a section of the country thickly settled with negroes and during the past few years a number of crimes against white women have been attempted.” Some of the alleged perpetrators, the Democrat insisted, had apparently escaped punishment, making the desire for vigilante justice stronger.

A number of witnesses appeared before the grand jury, including the law enforcement officers present at the jail and employees of the Cotton Belt Railroad who lived in the area of the Padgett house. While the testimony remained secret, it was rumored that the officers said they could recognize members of the mob by sight but did not know their names. Judge Grace, who had offered to testify, was apparently not called. In the end, no one was indicted for the crime. According to the May 29 edition of the Arkansas Gazette, “General opinion prevails that no information sufficient to indict any one connected with the mob that lynched Davis will ever be given. The sentiment here in favor of the participants in the ‘lynching bee’ is so strong, owing to the brutal attack on Miss Holmes…that it is doubtful if any man will ever face a jury for the violation of law involved in the mob’s action.”

For additional information:

“Grand Jury Inquires.” Arkansas Democrat, May 26, 1909, p. 4.

“Judge Grace Goes after Lynchers.” Arkansas Gazette, May 27, 1909, p. 1.

“Judge Grace to Probe Lynching.” Arkansas Gazette, May 26, 1909, p. 1.

“Making Thorough Inquiry in Lynching.” Arkansas Democrat, May 28, 1909, p. 12.

“Mob at Pine Bluff Lynches a Negro.” Arkansas Gazette, May 25, 1909, p. 1.

“Negro Admits Attack on Girl.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, May 23, 1909, pp. 1, 2.

“No Indictment against Lynchers.” Arkansas Gazette, May 29, 1909, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Lovett Davis Lynching Article

Lovett Davis Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.