calsfoundation@cals.org

Looking Back to See [Book]

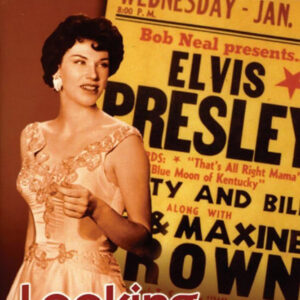

Looking Back to See is the autobiography of country music artist Maxine Brown. The book, published by the University of Arkansas Press in 2005, provides a detailed look at Brown’s upbringing in Arkansas, her family life during the Great Depression, and the musical career of the Browns—the group that made her famous. Taking her title from one of the Browns’ biggest hits, her memoir provides an unflinching look at her experiences in the music industry and the group’s eventual disbandment in the late 1960s. Brown died in 2019.

Maxine Brown was born in Louisiana in 1931, but she grew up in Arkansas in the Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) area. The family moved often when she was young. As a girl, she also spent time in Sparkman (Dallas County), Redfield (Jefferson County), Benton (Saline County), and Fordyce (Dallas County). She came of age during the Great Depression, and her childhood was typical of rural Arkansas in the 1930s. She wrote that she grew up in “the poorest land in the poorest part of the poorest state, but we never once had to eat worms.”

Brown’s childhood was similar to that of her contemporaries. As was true of fellow Arkansan Johnny Cash (born less than a year after her), Brown spent considerable time in the cotton fields. And like Cash, she hated the work. The similarities do not end there. Both Brown and Cash lost a brother (in Cash’s case, his older brother Jack) to a horrible accident when they were young. Maxine’s brother Raymond was run over by a logging truck in September 1943, witnessed by Maxine’s father and older brother Jim Ed. Her mother was pregnant at the time.

Brown wrote of her parents’ troubled marriage and the heavy toll their work took on them. Brown’s father, Floyd, was a logger who suffered the loss of a leg in a logging accident, forcing him to use a prosthetic limb for the rest of his life. Her mother, Birdie, ran a diner/grocery store that was destroyed by fire and then rebuilt several times. Her father was often unfaithful to her mother, though the couple never divorced. Her mother died in 1970—according to Brown, it was due to “overwork.”

Brown was raised in the Methodist Church and sought refuge in music. Her father played guitar when she was young, and extended family members were also musical. Brown and her siblings developed a unique, close harmony singing style. Making music, she wrote, “was better than ice cream, roller skates, or thrower’s country store.” Her influences included Roy Acuff, Eddy Arnold, the Carter Family, and the many Grand Ole Opry performers she heard over the years.

Despite family tragedy and troubles, Brown received a solid education. She graduated in 1950 from Watson Chapel High School in Pine Bluff, and she considered going to college. Instead, she took classes in business school and found a stable job working for the state police. The Browns—initially just her and her brother Jim Ed—got their first break at the Barnyard Frolic radio show in Little Rock (Pulaski County).

As the Browns built an audience through radio and television appearances, Brown became more serious about songwriting. Her father, who supported her music career, bought her a Martin acoustic guitar to help develop her talents. Her 1954 single “Looking Back to See” was based on her sister Bonnie’s school boy crush. Brown noted that she found the song “silly,” but it was an up-tempo hit, becoming one of the biggest country songs of the 1950s. Ray Charles, Buck Owens, and Guy Lombardo, among others, later recorded it.

But as Brown noted, the “path to the top is often paved with pain and tragedy.” The Browns became a trio when sister Bonnie joined the group in 1955. Despite their success, they received no royalties for their early songs. The reason for this was their swindling manager Fabor Robison. A predatory character, Robison signed unexperienced and naïve acts to contracts that diverted money to him. Robison controlled his roster of musicians with an iron fist, keeping them exhausted with constant touring while promising them money that never came—even as he was making a fortune. According to Brown, Robison was “the sorriest bastard then infesting the industry.” Her harsh view of him has been corroborated over the years by other musicians and music writers.

In Looking Back to See, Brown reserved her harshest words for Robison, but she spoke highly of people she met on the road such as Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, and Jim Reeves. Reeves, like the Browns, signed with Robison only to find himself with little to show for it. Reeves was a friend and mentor to the Browns until his death in a plane crash in 1964.

The Browns eventually freed themselves of their contract with Robison, signing with RCA and releasing their first songs with the label in March 1956. The Browns were successful in the 1950s, but they were never financially savvy. Their records sold well, but their financial situation remained precarious. Even after the Browns were selling millions of records, Maxine was still waiting tables at her mother’s restaurant. The group’s career was further disrupted when Jim Ed was drafted by the army (though he served stateside in Colorado rather than go overseas).

Brown wrote that she found little respite in her personal life. She described her marriage to husband Tommy as seven years of “pure hell.” She was a virgin when she got married at twenty-five, but her husband did not hold himself to any ideas of purity. He drank heavily and cheated on her. The couple had three children, but she wrote, “If you’re going to be in show business, you haven’t got a chance of being a normal person, much less a normal mother or wife.” Added to her stresses were physical problems from back pain and uterine cancer. She had successful surgeries, but her recovery was difficult.

The Browns, however, continued to win accolades. They became permanent members of the Grand Ole Opry, received awards, and were praised by the Beatles. They recorded “The Three Bells” in 1959, the group’s biggest hit, which was followed by another million-seller, “The Old Lamplighter.”

The 1960s were not as kind to the Browns as the 1950s were. Executives at RCA were not interested in the group long term. One higher-up at the label called Maxine Brown “old hat,” a slight that deeply wounded her ego and cast a dark shadow on the Browns’ future. She was also saddened by the lack of support from fellow Arkansans. In 1967, the group disbanded.

In 1969, Brown released her own album, Sugar Cane Country, but her solo career never took off. Her attempts to start a recording studio in Arkansas in the early 1970s proved unsuccessful. Her brother did well on his own, having a hit with “Pop a Top” in 1967, and he later hosted a television show. The Browns occasionally regrouped for live performances well into the 2000s, but Maxine’s music career was effectively over by the late 1960s. At the time Looking Back to See was published, she was living in Arkansas and dealing with vision problems. She had lost one eye to macular degeneration and was having problems with her other eye, too.

But she still had many fans, and Looking Back to See was well received. Bob Lancaster of the Arkansas Times wrote that Brown was “no great literatus,” but her memoir was a “sweet, likeable, and oddly compelling tale.” In 2012, the memoir won the Ella Dicky Literary Award named in honor of Missouri librarian Ella Dickey and given at the annual Cherry Blossom Festival in Marshfield, Missouri. According to the University of Arkansas Press, Brown’s book has sold thousands of copies, making it one of the best-selling books in the press’s history.

For additional information:

Brown, Maxine. Looking Back to See: A Country Music Memoir. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Lancaster, Bob. “Hardship behind the Browns’ Songs: Maxine Brown’s Memoir Recalls How the Trio Overcame Bad Fortune to Become among the Best of Country Music’s Groups.” Arkansas Times, April 8, 2005. https://arktimes.com/entertainment/books/2005/04/08/hardship-behind-the-browns-songs (accessed December 18, 2023).

Colin Edward Woodward

Richmond, Virginia

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Literature and Authors

Literature and Authors The Browns

The Browns  Looking Back to See

Looking Back to See

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.