calsfoundation@cals.org

Lake Village (Chicot County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 33º19’43″N 091º16’54″W |

| Elevation: | 125 feet |

| Area: | 2.38 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 2,065 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | February 7, 1898 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

1,074 |

1,449 |

1,582 |

2,045 |

2,484 |

2,998 |

3,310 |

3,088 |

2,791 |

2,823 |

|

2010 |

2020 | ||||||||

|

2,575 |

2,065 |

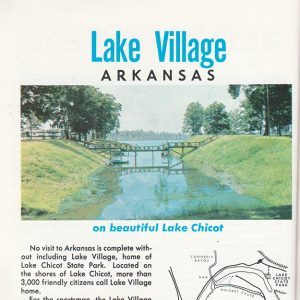

Lake Village is located in the extreme southeastern part of the state in Chicot County. While Lake Village is the smallest incorporated town, by square miles, in the county, it has served as the county seat since 1857. The hub of commercial activity for Chicot County, Lake Village prides itself on its rich agricultural background.

European Exploration and Settlement

While Lake Village was not incorporated as a town until 1898, the history of the area starts much earlier, beginning with the arrival of the Spanish in 1541. One local story claims that Hernando de Soto and his men came upon a friendly Native American tribe ruled by Chief Chicot, who had their village on the banks of the Mississippi River at the present-day site of Lake Village and who gave de Soto and his men food and skins for clothing. Though Hernando de Soto did die in 1542 at an Indian village likely near what is now Lake Village, there is no evidence of a Chief Chicot in the chronicles of the expedition. The names of Chicot County and Lake Chicot likely derive from a French word meaning “stump,” in reference to the many cypress knees in the area.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

While William Brawner was apparently granted property near the area in 1828, local legend says that the Pettit family became the first whites to settle the area, in 1830, with other families following between 1830 and 1840.

Agriculture was the mainstay of Lake Village. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, this meant plantation agriculture dominated by King Cotton and slavery. Lake Village was home to several of the largest slave holders in Arkansas and the South. By 1850, there were 145 white families in Chicot County owning a total of 3,984 slaves. The majority of these slaves lived in and around Lake Village.

Elisha Worthington became one of the wealthiest men in the South due in large part to plantations that he owned in and around Lake Village. At the height of his power, Worthington owned over 12,000 acres in Lake Village as well as some 540 slaves. In 1831, Joel Johnson bought a tract of land in Arkansas on the Mississippi River at a place called the “American Bend” and built Lakeport Plantation. His son Lycurgus built it into one of the most profitable plantations in the Arkansas Delta, holding, by 1860, some 4,500 acres of land and 155 slaves.

Lake Village has one of the oldest black churches in Arkansas. In 1860, Jim Kelley, a slave, founded the New Hope Missionary Baptist Church on a plot of ground that had been given to him by his master. Part of the church cemetery is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The first three years of the Civil War in Lake Village saw Confederate soldiers using guerrilla tactics on passing Union steamboats up and down the Mississippi River in Chicot County, with Union gunboats shelling the area indiscriminately in return. Only in 1864 did Lake Village experience a true battle. On June 6, 1864, 3,000 Federal troops under General A. J. Smith met Colonel Colton Greene’s 600 Confederates in the Engagement at Old River Lake. Despite having only one small cannon, the Confederates lost just four men, with thirty-three wounded, while Union army losses totaled 131 wounded or killed.

Afterward, Federal troops occupied Lake Village during the night, and injured soldiers filled virtually all the homes in the town, including the 1848 Saunders-Pettit-Chapman-Cook Plantation, which was used as an infirmary for soldiers from both armies. During the occupation, several houses were looted, several buildings were torched, and all livestock was shot. The town’s newspaper office was also destroyed.

The political prestige of Lake Village’s African-American community grew after the Civil War. James Mason, the son of Elisha Worthington and one of his slaves, became sheriff of Chicot County in 1872 and also served as a Republican boss and a state senator until he died in 1874. Black citizens of Lake Village continued to hold sway for some years to come, holding most of the elected offices in the town for fifteen years after the war.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

While Sunnyside Plantation had been operational as early as 1830, it was not until the 1880s that national interest in the plantation arose. Austin Corbin, a New York banker and businessman, bought the plantation in 1886 and, in 1895, made an agreement with the mayor of Rome, Italy, to bring 100 Italian families to Sunnyside Plantation. Corbin and his business partners were quickly accused of keeping the Italians in a state of debt peonage. The federal government intervened, and by the turn of the century, many of the Italian families had moved to Tontitown (Washington County) in northwest Arkansas.

Early Twentieth Century

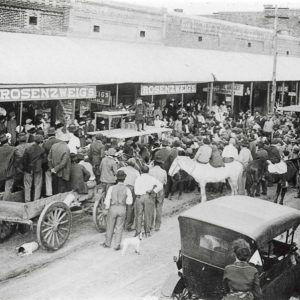

The coming of the Memphis, Helena, and Louisiana Railroad in 1903 resulted in steady population growth. In 1907, the old courthouse was demolished and a second one was built in its place. By 1910, the population was just over 1,000—a 700 percent increase since 1900. That same year, a city water works system was put in place, and concrete sidewalks were laid. In 1912, Main Street was paved, and Lake Village’s first sewage system was added. In 1918, the first U.S. Highway in Arkansas (Highway 65) was completed through Lake Village, and, in 1920, this became the first all-weather road in the state. Robert Hicks, a young African-American man, was lynched in November 1921 for writing a letter to a young white woman. In April 1923, Charles A. Lindbergh made his first night flight from Lake Village, commemorated by a marker still visible from the take-off point on North Lakeshore Drive.

The Flood of 1927 put much of Main Street in Lake Village under water, causing extensive property damage and a few deaths. The people of Lake Village used boats to get around downtown and even erected wooden scaffolding so businesses could stay open. The flood also affected the dams, spillways, and natural streams in the area that carried the water away from the farmlands, turning Lake Chicot from a crystal-clear body of water to a settling basin for the muddy waters of ditches and bayous as far away as Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). The Great Depression compounded the hard times of the townspeople.

World War II through the Faubus Era

During World War II, Lake Village was the site of a small German prisoner-of-war (POW) camp, established on July 7, 1944, as a branch of the main camp in Dermott (Chicot County). At its height, the POW camp in Lake Village housed over 300 enlisted German men, most of whom were considered Nazi sympathizers. The camp was in operation until March 23, 1946.

The second courthouse was razed and replaced with the current courthouse in 1956. The Lake Village Confederate Monument is located nearby.

Lake Village was late to desegregate its schools after the Brown decision in 1954. It was not until 1969 that Larry Potts became the first black student to graduate from Lakeside High School. It was not really until 1970 that full integration came to Lake Village’s school system.

Modern Era

The Lake Chicot Restoration Project began in August 1976 and was completed in April 1985. The relatively successful project diverted muddy waters away from the lake and into the Mississippi River. Another boon to the lake was the creation of a fifty-foot bridge connecting both sides of the lake in the early 1990s. Before this bridge was built, the northern and southern portions of the lake had been separated by a causeway.

Agriculture has always been of major importance to the economy of Lake Village, especially because proximity to the Mississippi River has long provided easy transportation of goods. While cotton continues to be a large part of the agricultural sector of the town, soybean production has surpassed it. Corn has also received a boost in Lake Village due to its use as an alternative fuel source. Many farmers around Lake Village devote acreage to rice and wheat, which command high prices. Catfish farming has also seen a great increase in the early twenty-first century, though the majority of the catfish comes from neighboring Eudora (Chicot County).

Other major employers in Lake Village outside of agricultural industries include the Bank of Lake Village, Simmons Bank, Chicot County Memorial Hospital, Paul Michael’s, and Delta Spindle and Manufacturing Company, which produces cotton-picker spindles. Recent additions to Chicot Memorial Hospital have made it state of the art. The town has an industrial park two miles west of the main business district. The park has sixty-four acres of available land fully developed. It is an Arkansas Enterprise Zone, part of a program to stimulate business and industrial growth in the depressed areas of the state.

The Benjamin G. Humphreys Bridge linked Lake Village to Greenville, Mississippi, in 1940. Before that, residents of Lake Village had to take a ferry across the river. The new Greenville River Bridge was ready for traffic in the spring of 2010. This new bridge is the longest cable-stayed bridge on the Mississippi River.

Attractions

Lake Chicot is the largest oxbow lake in North America as well as the largest natural lake in Arkansas. Lake Chicot State Park is located on 211.6 acres on the northern shores of the lake and offers 127 individual campsites as well as fourteen fully equipped cabins. The Chicot County Park also has campsites. The Lake Chicot Water Festival included national championship hydroplane boat races, bringing in competition from all over the state. However, this festival was discontinued in favor of the Harvest Festival in the fall that highlights the town’s ties to agriculture. The restored Lakeport Plantation, now a heritage site and museum maintained by Arkansas State University, opened to the public in 2007. The site preserves the state’s only remaining plantation home on the Mississippi River. In addition, Lake Village is one of only nineteen places in the state where Depression-era post office art may be viewed. The Dr. E. P. McGehee Infirmary is also on the National Register of Historic Places.

Notable Figures

Lake Village was home to Confederate general and state Senator Daniel Reynolds and civic leader Sam Epstein. Lake Village was also the birthplace of Communist Party activist Claude Lightfoot. Arkansas Supreme Court justice Samuel Dunn Robinson grew up in Lake Village. Lamar McHan, a star of the Canadian Football League, was born and grew up in Lake Village.

For additional information:

Daniel, Pete. Deep’n as it Comes: The 1927 Mississippi River Flood. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

DeBlack, Thomas A. “A Garden in the Wilderness: The Johnsons and the Making of Lakeport Plantation, 1831–1876.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, 1995.

Shea, William. “Battle at Ditch Bayou.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Autumn 1980): 195–207.

Simons, Don. In Their Words: A Chronicle of the Civil War in Chicot County, Arkansas, and Adjacent Waters of the Mississippi River. Sulphur, LA: Wise Publications, 2000.

Whayne, Jeannie M., ed. Shadows over Sunnyside: An Arkansas Plantation in Transition, 1830–1945. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Scott Cashion

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

I am a 1969 graduate of Lakeside High School. Larry Lee Potts (and his younger sister Linda) began attending Lakeside under “freedom of choice” in the fall of 1966. Three black families enrolled their children at the formerly all-white junior and senior high school that year. Larry was part of the graduating class in 1969.