calsfoundation@cals.org

Jess Orval Dockery (1909–1997)

Jess Orval Dockery was an aviation pioneer and an innovator of agricultural aviation in the Mid-South region, based first in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) and, later, Stuttgart (Arkansas County) and Clarksdale, Mississippi. He played a leading role in developing aerial application processes, perfecting the science of crop dusting and spreading the practice to the Midwest.

Jess Orval Dockery was born on February 26, 1909, in Dallas, Texas, to Jess P. Dockery and Myrtle Kemp Dockery. Confederate general Thomas Pleasant Dockery was his great-uncle, while socialite Octavia Dockery was a cousin. During World War I, his family moved to Lawton, Oklahoma, where his father ran a jitney service to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. This gave Dockery access to the base’s aircraft, leading to a keen interest in flying. By 1921, the Dockery family lived in Corpus Christi, Texas. A pilot landed there that year and gave Dockery a ride, showing him the basics of flying. While guarding the aircraft for the pilot, the twelve-year-old enthusiast took off in the plane and flew solo. Impressed, the pilot allowed him to haul passengers in his planes, making Dockery a pre-teen barnstormer. Shortly after this, the family relocated to Pine Bluff.

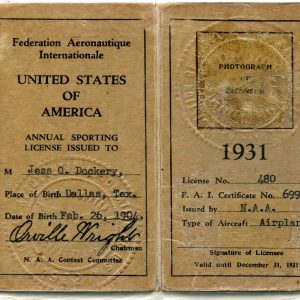

In addition to giving aerial tours, offering flight instruction, and barnstorming, Dockery began acrobatic flying around 1923. He was the ninetieth American to receive a pilot’s license, with his being signed by Orville Wright. While flying for Burrell Tibbs’s Flying Circus in Oklahoma City, Dockery helped give flight lessons to Wiley Post, who became Will Rogers’s personal pilot and the first pilot to fly solo around the globe. He taught author John Faulkner to fly a plane, as well as Paul Braniff, who went on to start an airline. Dockery flew for the Gates Flying Circus, Texas Flying Circus, and Lone Star Flying Circus before government regulations largely curtailed barnstorming.

In the summer of 1924, an event that drastically changed and improved agriculture took place in Scott, Mississippi. Dockery and his Pine Bluff associate Allen Scott (with Dockery doing the flying) performed a crop-dusting operation for Delta & Pine Land Company, the region’s largest cotton-growing enterprise. This was considered the beginning of commercial aerial application in the Lower Mississippi Valley. The success of this operation attracted Huff-Daland Dusters, which had just begun similar flights at its Macon, Georgia, base, to relocate to Monroe, Louisiana, and later expand its business into today’s Delta Airlines. In 1926, Dockery attended the International Balloon Races in St. Louis, Missouri, where he met and formed a friendship with Charles Lindbergh. That year, at the age of seventeen, he flew the mail between St. Louis and Chicago, Illinois, with Lindbergh, in the employ of Robertson Aircraft Corporation, a predecessor of American Airlines. The next year, he flew for Mid-South Airways in Memphis, Tennessee.

On March 28, 1927, Dockery married Irene Borman. They had two daughters.

Dockery became a test pilot for Cessna Aircraft in Wichita, Kansas, and after that, one of the first three pilots for Braniff Airlines in Oklahoma City.While chief test pilot for Garland Aircraft in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1930, he experienced the only forced parachute jump of his career.

Dockery’s greatest feat in exhibition flying occurred at the 1932 New Orleans Air Carnival, where he was the only pilot to evade a battery of searchlights. He was singer Jimmie C. Rodgers’s pilot for a time and, in that era, he was billed as the nation’s best stunt pilot. In 1934 and 1935, he won the Miami Air Races. In the 1930s, Dockery set up an agricultural flying service in Stuttgart and Clarksdale, which he operated for over thirty years. He designed his own chemical hoppers, based on the type of aircraft used. In 1938, he was the first person in the Mississippi Valley to seed rice from an aircraft, perfecting the operation on several hundred acres of the Wallworth farm near Stuttgart.

During World War II, Dockery flew for the Army Air Forces Ferrying Command as a check pilot and instructor, drawing from his experience flying heavy loads while dusting. He declined a major’s commission to return to his flying service, which was deemed more critical to the nation’s war efforts. At this time, he began an aphid-control program for vegetable farmers in and around Wisconsin, which continued for over twenty-five years in a contract with Green Giant Foods. He also conducted mosquito-control spraying at defense plants. Dockery owned as many as sixty aircraft at a time over his career, including models made by Travel Air, Waco, Standard, Curtiss, Stinson, Ford, Aeronca, Fairchild, and Stearman. In 1948, he landed a Cessna on the Broadway Bridge in Little Rock (Pulaski County), with four feet of clearance, to deliver the plane to Robinson Auditorium for a trade show. When he quit logging flights in the 1960s, he had flown over 50,000 hours.

After retiring from agricultural aviation in the late 1960s, he was sales manager for Bellanca Aircraft in Florida. He worked into the 1990s as a tour pilot and flight instructor while in his eighties. Dockery flew passengers for seven decades without accident or injury to any of them, only suffering one minor personal injury in all his years flying. He dusted crops in twenty-six states, Mexico, and Central America. At one point, he was one of only four pilots licensed to fly all types of land-based aircraft.

Dockery died on December 20, 1997, in Navarre, Florida. In 2019, he was inducted into the Arkansas Aviation Hall of Fame.

For additional information:

Allbright, Charles. “The Best Is Memory.” Arkansas Gazette, December 12, 1975.

———. “Flyin’ High—and All Alone.” Arkansas Gazette, December 11, 1975.

Allen, Garner. “City Airman, Pilot at 13, Pioneered in Agri Aviation,” Stuttgart Daily Leader, June 26, 1953, p. 1, 5.

Anderson, Mabry I. Low & Slow: An Insider’s History of Agricultural Aviation. Clarksdale, MS: Low & Slow Publishing Co., 1986.

Baxter, Gordon. “On the Trail of the Phantom Waco.” Flying 93 (October 1973): 113–114, 123.

Elliott, Robert G. “Jess Orval Dockery: A Flying Silver Eagle, Part I.” Vintage Airplane (July 1980): 12–16.

———. “Jess Orval Dockery: A Flying Silver Eagle, Part II.” Vintage Airplane (August 1980): 12–18.

Husted, Bill. “He’s Got a Prop for Hair, Wings for Arms.” Arkansas Democrat, February 3, 1974, pp. 1A, 8A.

“J. O. Dockery—His Career Began at 12.” Propwash (January–February 1963): 10–11.

“J. O. Dockery—Most Presciently Named.” Arkansas Gazette, December 10, 1975.

Lancaster, Bill, ed. “Dockery Celebrates 69 Years of Flight.” AgAir Update 37 (February 2019): B18–B24.

Mosenthin, H. Glenn. “Jess Orval Dockery: Stuttgart’s Pioneering Aviator.” Grand Prairie Historical Bulletin 62 (April 2019): 2–15.

———. “Some Notes on J. O. Dockery.” Grand Prairie Historical Bulletin 42 (April 1999): 60–62.

Skelton, B. J. “Daddy of the Dusters.” Delta Review (September–October 1965): 26–31.

Storey, Celia. “Bridge Was Once a Runway for Plane.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 3, 2016.

Young, Bill. “Stuttgartian Boasts Long History in Aviation.” Stuttgart Standard, December 11, 1969.

H. Glenn Mosenthin

Searcy, Arkansas

Aerial Seeding

Aerial Seeding  Dockery License

Dockery License  Irene and J. O. Dockery

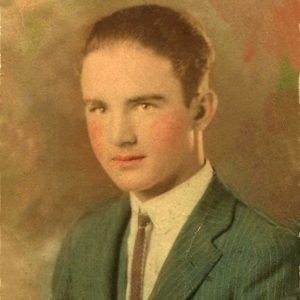

Irene and J. O. Dockery  J. O. Dockery

J. O. Dockery  Dockery Airport

Dockery Airport  Rice Seed Loading

Rice Seed Loading  Stearman Crop Duster

Stearman Crop Duster

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.