calsfoundation@cals.org

J. W. Gibson (Murder of)

On December 23, 1920, in what one newspaper called “One of the most dreadful tragedies that the Negroes of the City of Helena has [sic] ever been called on to witness,” Professor Jacob William (J. W.) Gibson was killed by a night watchman in Helena (Phillips County). Depending on how the word “lynching” is interpreted, this may have been an incident of police brutality, or Professor Gibson may in fact have been lynched.

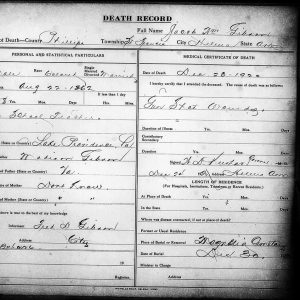

The Arkansas Gazette filed no report on Gibson’s death. The only national coverage appears to be a rather belated report in the Dallas Express, an African-American newspaper published in Texas. Not much is known about Gibson. According to the Express, not only did Gibson teach in Helena, but he had a farm in Cotton Plant (Woodruff County). According to the 1920 census, one James Gibson, a “mulatto,” lived on a rented cotton farm in Freeman Township of Woodruff County with his wife and three children; he had earlier registered for the World War I draft. His death certificate lists his date and place of birth as August 22, 1862, in Lake Providence, Louisiana, while his occupation is that of a teacher.

On December 23, carrying a shotgun, Gibson apparently left his farm and took the train to Helena, where he arrived at 7:35 p.m. and then stopped to get a shave and a haircut. Afterward, as he was standing on the corner of Cherry and Missouri streets waiting for the streetcar, a night watchman (never identified by name) approached him and asked him to turn over his shotgun. Gibson replied that he was carrying no shells for it. The watchman asked him why, and Gibson said that he felt no need to carry any. The watchman then asked to search his “hand bag” but found only books and papers. According to the Express, at this point, he asked Gibson, “What kind of nigger is you?” Gibson reportedly replied that “he was a man the same as the night watchman was.” The watchman then allegedly struck Gibson across the face before taking the shotgun and hitting him with it. He then marched him up Cherry Street to the jail.

A short while later, according to the Express, a local druggist, Dr. J. W. Jennings, called the jail and asked the watchman to release Gibson, offering to make sure Gibson would be available for any subsequent court appearance. Jennings was African American and a graduate of the Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College in Mississippi. According to the Huntsville, Alabama, Daily Times, at the time of the Elaine Massacre in 1919, he and A. R. Dupree, who owned a cleaning establishment in Helena, had been arrested and “charged with distributing pernicious propaganda.” When Jennings contacted the jail about Gibson, the watchman reportedly replied, “I have just killed that d—- Nigger.” The means by which Gibson was reportedly killed are not mentioned in the report. However, Gibson’s death certificate lists the cause of death as “gun shot wound.”

According to the Express, Gibson’s body was taken to an undertaker, where his relatives were able to retrieve it the following day after being forced to pay for embalming and a coffin. An inquest was called for December 25, but since that was Christmas, it was adjourned until December 28. There is no information as to whether the inquest ever took place. The Express lamented Gibson’s death, reporting that “he was identified with everything for the advancement of the community and for the race, and stood high in all kinds of lodges being a Mason with all of the degrees from the first to the thirty-third.” According to his death certificate, he was buried in Magnolia Cemetery in Helena on December 30, 1920.

Whether Gibson’s death is a simple murder or a lynching is open to interpretation. Modern historians such as W. Fitzhugh Brundage, author of Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930, assert that any lynching has to be the result of mob violence. Indeed, according to historian Christopher Waldrep, author of African Americans Confront Lynching: Strategies of Resistance from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Era, the guidelines decided upon by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other organizations in 1940 defined lynching “as an activity in which persons in defiance of the law administer punishment by death to an individual for an alleged offense.” The Case anti-lynching bill, introduced in 1947, stipulated that at least two individuals must be involved. There are, however, less restrictive definitions of lynching. For example, according to the Texas State Historical Association, “Lynching is the illegal killing of a person under the pretext of service to justice, race, or tradition. Though it often refers to hanging, the word became a generic term for any form of execution without due process of law.”

Under this latter definition, Gibson’s death was a lynching, and it has many of the other common characteristics of such incidents. Like the lynchings described in the NAACP report, the killing was inflicted “in defiance of the law” on “an individual for an alleged offense.” It also fits Brundage’s description of many lynchings, in that the victim was murdered “with little if any regard for proof of guilt or evidence of innocence.” Brundage also notes that in many cases, law officers failed to prevent the incidents, and in some cases, as in Gibson’s murder, they were actually complicit. As with many lynchings, especially after World War I, notes Brundage, such events were not only intended “to enforce social conformity and to punish an individual, but they also were a means of racial expression.”

For additional information:

“Prof. Gibson, Arkansas Teacher Shot to Death.” Dallas Express, January 15, 1921, p. 1. Online at http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth278336/m1/1/ (accessed December 23, 2025).

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.