calsfoundation@cals.org

Hutchinson (Independence County)

The community of Hutchinson is located atop Hutchinson Mountain in Independence County, about eight miles from the county seat of Batesville. Families that settled in the area have remained there for generation after generation.

Two of the first settlers on the mountain were William Goodman and Ziba Danual Barber from Tennessee. The families united when Ziba Barber married Permelia “Permiba” Goodman, William Goodman’s daughter. Family lore has it that Ziba was killed by jayhawkers during the Civil War in 1864. One of the couple’s sons, Andrew Jackson Barber, married Cynthia Ann “Sinthy” Graddy, the only child of another mountain pioneer, Lewis Graddy (or Grady). Lewis Graddy and his older brother, John Graddy, stopped in Independence County on their way to join up with the Mexican War. There, Lewis Graddy met Susannah Linebarger, and the two were married. John Graddy later married Susannah Long in the holler by the mountain. The Goodman, Barber, Graddy/Grady, and Linebarger families still inhabit the area today.

The Linebargers became one of the most prominent families on the mountain as a result of Peter Linebarger being the only blacksmith for the region. During the Civil War, he was chosen to lead the Independence County Home Guard and Minute Men in Caney for the Confederacy. The Linebarger home place sat on the edge of the mountain overlooking the valley, which is today called McHue. Remains of the home place are still visible. Peter Linebarger’s niece Mary Elizabeth Linebarger married Joseph Thomas Kyler; Kyler Cemetery on Kyler Road at the foot of the mountain is named for Joseph Kyler’s father, John Kyler, who was Independence County judge from 1844 to 1846. Enoch Green Strother, John Daniel “Jack” Rutledge, Samuel David “Bud” Lambert, George Washington Altom, Levi Turner, Devericks Gerius “Dexter” Hays, and others came to the mountain after the Civil War and married into the families already making their homes there.

Before Hutchinson, there was no single community for the mountain. The three separate communities of Pull Tight, Enterprise, and Mineral Springs existed, and each had a school with grades 1–8. These three schools were first consolidated into the Consolidated Hutchinson Mountain School in 1929. In the early 1950s, this school was, in turn, consolidated with Floral, Southside, and Pleasant Plains. On the early census reports for the area, the names Round Pond and then Caney designated a portion of the mountain area. The main part of the mountain was in the Relief Township. Hutchinson connected to the surrounding communities of Jamestown, McHue, Huff, Floral, and Pleasant Plains, with most of the residents having family ties to those regions. In the twenty-first century, the address for Hutchinson is Floral, and there is a road called the Jamestown Loop. Many today even refer to the mountain as Strother Mountain after one of the prominent families living there.

A post office was established on the mountain on June 20, 1900. The first postmaster was Edwin Henry Hutchinson, who had been born in Manchester, Lancashire, England, in 1847, and had previously been postmaster in Hazen (Prairie County). He and his wife, Maggie Rachels Hutchinson, also had a general store with the post office. The community and mountain came to be called Hutchinson. The post office and general store was taken over by William Frederick (Bill) Graddy (or Grady) on February 24, 1905. He operated it until it closed on October 31, 1933. The post office was located in what was called the Huff–Rocky Point–Starnes Spring Triangle.

Life on Hutchinson Mountain was not easy. The soil is unsuitable for many crops or for large farms, but corn can be grown, from which some locals derived moonshine. Cattle and timber provided means of support for residents, as did the poultry business. J. K. Southerland, a successful poultry entrepreneur, came from the Floral area.

Residents also did migrant work to support themselves. During strawberry season, pickers from Hutchinson and McHue would travel to Velvet Ridge (White County) and Bald Knob (White County) for the harvest, while others traveled to the state’s Arkansas Delta region to pick cotton or even out of state for other migrant agricultural labor, as happened in 1951 and 1952 when local families caravanned to Indiana for the tomato harvest.

The only church building in the community is the Church of Christ located near the old Bill Graddy place, not far from Salado Creek; the main cemetery for the mountain, called Palestine, is behind the church. The main highway is called Camp Tahkodah Road and takes its name after Camp Tahkodah, a ten-acre Church of Christ camp established in the 1930s by Harding University in Searcy (White County) on the banks of Salado Creek. Upstream from the camp was the private Grady Hole, with swimming facilities and cabins.

Though violence has flared a few times on the mountain concerning property rights, moonshine territory, and family feuds, the event that gained the most notoriety took place on March 20, 1922, and concerned the dipping of cattle to eradicate the cattle tick. Many on the mountain refused the government orders to dip their cows in vats at various locations, instead forming anti-dipping groups. The anti-government stance reached its apex when cattle inspector Charles Jeffrey was riding along with a helper, Lee Harper, on the road leading to Jamestown. From the brush, shots rang out, and Jeffrey fell from his horse, mortally wounded. Lee Harper was wounded but lived. Much effort was expended to find the shooter or shooters, but to no avail. No one was ever charged, for lack of evidence, though nine were arrested and seven indicted on charges of “conspiracy to commit murder.”

In the twenty-first century, there are no stores on Hutchinson Mountain, no post office, no schools, and only one church. However, Harding University still operates Camp Tahkodah there.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northeast Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1889.

McGinnis, A. C. “A History of Independence County, Ark.” Special issue. Independence County Chronicle 17 (April 1976).

Mosier, Susan. “The 1922 ‘Tick War’: Dynamite, Barn Burning, and Murder in Independence County.” Independence County Chronicle 41 (October 1999–January 2000): 3–22.

———. Hutchinson Mountain, Volume II, 1998.

Kenneth W. Rorie

Van Buren, Arkansas

Camp Tahkodah

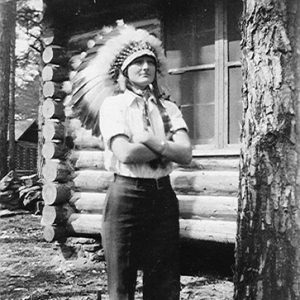

Camp Tahkodah  May Grady

May Grady  Hutchinson Post Office

Hutchinson Post Office  Hutchinson Mountain Church of Christ

Hutchinson Mountain Church of Christ  Independence County Map

Independence County Map  Mountain Still

Mountain Still  Pull Tight School

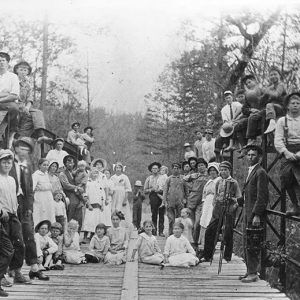

Pull Tight School  Salado Creek Bridge

Salado Creek Bridge  Strother Homestead

Strother Homestead  Strother Mill

Strother Mill

I have family still living on the Mountain, although the younger generations I am not familiar with. I always loved visiting the Mountain and my family who resided there. My Daddy was TJ Lambert, son of Levi and Martha Marie Smith Lambert. He was instrumental in giving me a love for history and beauty of the Mountain.

I lived on Hutchinson Mountain as a child. My grandfather was a preacher at times at the Church of Christ. He was tried for the murder of the anti-dipping leader. He died in 1932, two years before I was born. Grandma used to tell me stories about the cattle dipping, and on our main farm we had a dipping place and a large stone that was used to crush the cane stocks to make molasses. The cattle were infested by ticks, and some died and others lost a lot of weight–and, of course, money was lost when they were sold. I think that the anti-dipping group considered the dipping to be cruelty to the cows. We had a group of mailboxes north of our farm, and I saw the mailman come on a horse to deliver mail.