calsfoundation@cals.org

Hilda Cornish (1878–1965)

aka: Brunhilde Kahlert Cornish

Brunhilde Kahlert Cornish was the founder of the Arkansas birth control movement. She was instrumental in founding the organization that became the Planned Parenthood Association of Arkansas.

Hilda Kahlert was born on January 24, 1878, in St. Louis, Missouri, to German immigrants Sophie and Rudolph Kahlert. Her father was a carpenter, and her early life as a worker and as an observer of working-class struggles informed her about a broad spectrum of life experiences.

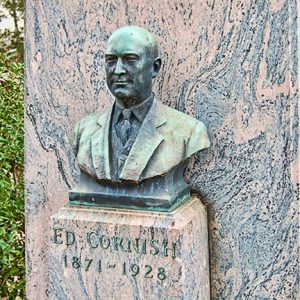

After earning a high-school diploma, Kahlert left St. Louis to work as a milliner in New York. She moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1901 and married a widowed banker, Edward Cornish, in July 1902. The couple had six children between 1904 and 1917. Cornish focused on raising her children during the first two decades of her married life, but she also did volunteer work. She served on the board of managers of the Arkansas State Farm for Women, a correctional institution, and as an officer of the Arkansas Federation of Women Clubs. She was appointed by Governor Thomas C. McRae to lead volunteers aiding victims of the Flood of 1927 in Arkansas.

Cornish’s husband committed suicide in 1928. After his death, she devoted much of her time to reform and social work. In the summer of 1930, she met Margaret Sanger, the founder and leader of the American birth control movement. The two developed a friendship maintained by correspondence and occasional meetings. During that summer, Cornish visited Sanger’s Clinical Research Bureau in New York, and she launched the Arkansas birth control movement later that same year.

At Cornish’s initiative, a group of physicians, business and religious leaders, and women active in civic work formed the Arkansas Eugenics Association (AEA). Rabbi Ira Eugene Sanders said, “It was suggested that because the movement might evoke criticism on the part of the rather orthodox and staid community, that we call it the Arkansas Eugenics Association on the grounds that nobody would object to being well born.” In early 1931, the association opened the Little Rock Birth Control Clinic in the basement of Baptist Hospital. There, poor white women could get contraceptives at a time when men and women urgently sought to limit the size of their families.

What motivated Cornish and her fellow birth control advocates must be understood in the context of economics and the Great Depression. The AEA strongly argued that, as a consequence of the current economic hardships facing many, it was necessary to limit the number of children born into poor families. Information disseminated by this group played on peoples’ fear that the poor were gaining in numbers and that this would add to the financial burden of all taxpayers—birth control was a solution offered to prevent “future charity cases.” Leading individuals in the medical, religious, and women’s volunteer groups spearheaded this local birth control movement. There was not much public resistance, possibly because the group opted to associate publicly with the eugenics movement rather than with the American Birth Control League and Margaret Sanger. Leaders and members of the AEA Board of Governors were: Rabbi Ira Sanders; Hay Watson Smith, a respected leader of the Second Presbyterian Church; Graham Roots Hall, a respected lawyer; Homer Scott, chief of staff at the Arkansas Children’s Hospital and a well-respected obstetrician; Darmon Artelle Rhinehart, president of the Arkansas Medical Society.

The Arkansas Eugenics Association reached its immediate goal when several medical units across the state in the late 1930s began to give contraceptive advice to women of limited means. Until the clinic opened, only those women who could afford a private physician had access to safe, effective contraceptives. African American women had to wait until 1937 for the clinic to open its doors to them.

Cornish also worked with the National Committee on Federal Legislation for Birth Control. This group, led by Margaret Sanger, was formed to influence legislators and the public to change laws that obstructed free access to contraceptive information. In the 1936 United States v. One Package case, this legal barrier was eliminated, and both medical and public opinion became more favorable.

By 1940, many medical units across the state included birth-control services. The Arkansas Eugenics Association changed direction and limited its work to referrals and education. The organization changed its name to the Planned Parenthood Association of Arkansas in 1942. Cornish spent the next two decades lobbying for the inclusion of contraceptive services in the public health system. Her goal of access to safe, effective contraceptives was realized when the state health department took on the responsibility of distributing contraceptives to the public in the mid-1960s.

Cornish remained involved in community activities. She had been a charter member of the Women’s City Club, serving as its president in 1934–35. She was also active in the Democratic Party during the 1940s.

Cornish died on November 19, 1965, and is buried in Oakland Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Arkansas Eugenics Association and the Little Rock Birth Control Clinic Files. History of Public Health in Arkansas Collection. Archives Collections. University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Library, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Arkansas Women’s History Institute Collection Biographical Files of Little Rock Women. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Leung, Marianne. “‘Better Babies’: The Arkansas Birth Control Movement during the 1930s.” Ph.D. diss., University of Memphis, 1996.

———. “Hilda Kahlert Cornish (1878–1965): A Community Volunteer and Civic Leader: The Birth Control Movement in Arkansas.” In Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, edited by Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary T. Edwards. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

———. “Making the Radical Respectable: Little Rock Clubwomen and the Cause of Birth Control during the 1930s.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Spring 1998): 17–32.

Margaret Sanger Papers. Manuscript Division. Library of Congress, Washington DC.

Welch Melanie K. “Not Women’s Rights: Birth Control as Poverty Control in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Autumn 2010): 220–244.

———. “Politics and Poverty: Women’s Reproductive Rights in Arkansas, 1942–1980.” PhD diss., Auburn University, 2009. Online at https://etd.auburn.edu/handle/10415/1716 (accessed October 5, 2023).

Marianne Leung

Lausanne Collegiate School

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.