calsfoundation@cals.org

Henri de Tonti (1649–1704)

aka: Henry de Tonty

Henri de Tonti helped establish the first permanent European settlement in the lower Mississippi River Valley in 1686. It was called the Poste aux Arkansas, or Arkansas Post. As a result, de Tonti is often called the “father of Arkansas.” Although Italian by birth, de Tonti is associated with French exploration. He received notoriety as an explorer in the Great Lakes Region and Mississippi River Valley with his friend, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, at a time when the French were establishing trade monopolies in parts of North America to compete with the English and Spanish.

Henri de Tonti was born around 1649 near Gaeta, Italy, to Lorenzo de Tonti and Isabelle di Lietto. The family moved to Paris, France, soon after his birth so that his father could escape being persecuted in an unsuccessful revolt against the Spanish viceroy in Naples. In 1668, while still a youth, de Tonti enlisted in the French army and served as a cadet. Later, he served in the French navy and lost his right hand in a grenade explosion during the Sicilian wars. He substituted a metal hook, over which he wore a glove, thus earning him the nickname, the “Iron Hand.”

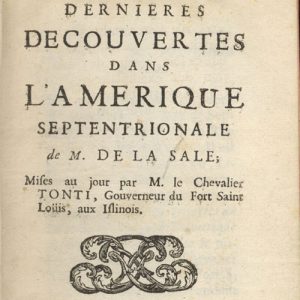

De Tonti first came to North America with La Salle in 1678 and was placed in charge of several French forts in the Great Lakes region. In 1682, de Tonti—now a lieutenant—accompanied La Salle on a journey south to explore the Mississippi River Valley region and to help establish alliances with the Native Americans of the area. On this journey, he witnessed ceremonies claiming the land in the lower Mississippi River Valley for the French king, Louis XIV. One of these ceremonies was held at the present-day site of Arkansas Post National Memorial in Arkansas County in the presence of Quapaw Indians. Afterward, de Tonti received from La Salle a land grant about thirty-five miles from the mouth of the Arkansas River near the Quapaw village of Osotouy in 1682. After exploring the lower Mississippi River Valley with de Tonti by his side, La Salle left for France in order to collect colonists to settle Louisiana. He placed de Tonti at the fur trading post of Fort Saint Louis on the Illinois River in 1683, one of the only western forts to remain open after the French colonial government decided to concentrate their fur trade efforts in Montreal. De Tonti was not pleased with this assignment and sent La Salle letters asking him to return and assist him.

After assuming that he would meet up with La Salle as he ascended the Mississippi River when he returned from France, de Tonti left Fort Saint Louis and headed south in 1686. Instead of meeting La Salle, de Tonti went to Arkansas to establish a trading post. He left behind six Frenchmen to build a trade house and secure a permanent French settlement, engage the Quapaw in trade, serve as a way station for travelers between the Illinois country and the Gulf of Mexico, and establish a presence in the middle of North America to stop English invasion from the east. De Tonti called himself the feudal lord, or the “Seignor [sic] [of] the City of Tonti and the river of Arkansas.” As feudal lord, de Tonti held legal authority over certain cases in his territory, but it is most likely he never held court or even executed many legal decisions.

De Tonti left Arkansas in 1687 but returned several times in the 1690s to review affairs at his trading house. He found the trading post failing economically because it was hard to reach and was burdened with a moratorium that Louis XIV had placed on beaver pelt trade south of Canada. De Tonti had to enforce this royal edict in 1698, making many French hunters and traders angry with him and resulting in further desertion of the post and the area. As a result, it was not until the early 1700s that the French were able to send more settlers over to increase the population of Arkansas Post.

De Tonti did not return to Arkansas Post after the 1690s. Instead, he fought against the English and the Iroquois while helping to conduct treaties with American Indian tribes. In 1688, de Tonti returned to Fort Saint Louis and learned of the death of La Salle. In the 1690s, he traveled to present-day Texas to find the survivors of La Salle’s expedition but left the area after receiving little help from the local American Indian tribes. In the early 1700s, de Tonti was chosen by Pierre Moyne, Sieur d’Iberville, founder of the Louisiana colony, to make peace between the Choctaw and Chickasaw. He served under Iberville’s brother, Jean Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, to bring the two nations together as a treaty negotiator. He also led expeditions in the Gulf Coast regions until 1704.

In September 1704, de Tonti contracted yellow fever and died at Old Mobile (present-day Mobile, Alabama). According to local lore, de Tonti’s “remains were laid to everlasting rest in an unknown grave near Mobile River, and not far from the monument erected in 1902 to commemorate the site of old Mobile.”

Tontitown, named in honor of de Tonti, was founded in 1898 by a group of Italian Catholic immigrants led by their priest, Father Pietro Bandini.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris S. The Arkansas Post of Louisiana. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2017.

———. Colonial Arkansas, 1686–1804: A Social and Cultural History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

———. Unequal Laws Unto a Savage Race: European Legal Traditions in Arkansas,1686–1836. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1985.

Arnold, Morris, Jeannie M. Whayne, Thomas A. DeBlack, and George Sabo III. Arkansas: A Narrative History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Caldwell, Norman W. “Tonty and the Beginnings of Arkansas Post.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 8 (Autumn 1949): 189–205.

Coleman, Roger. The Arkansas Post Story. Santa Fe: Division of History, Southwest Cultural Resources Center, Southwest Region, National Park Service, Department of the Interior, 1987.

Higginbotham, Jay. “Henri de Tonti’s Mission to the Chickasaw, 1702.” Louisiana History 19 (Summer 1978): 285–296.

Malone, Dumas, ed. Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. 9, Sewell to Trowbridge. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1935.

Murphy, Edmund Robert. Henry de Tonty, Fur Trader of the Mississippi. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1941.

Owen, Thomas McAdory. History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography. Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1921.

Lea Flowers Baker

Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

I’ve lived in Tontitown, Arkansas, the small town named after de Tonti, since 1986. Settlement of this community is an interesting story. In the late 1800s, a group of Italian immigrants contracted to plantation owners in the southeast Arkansas lowlands, in the Mississippi River delta, to work the plantations to repay help in immigrating. Disease was rampant in those swampy lowlands, so an Italian priest, Father Pietro Bandini, located and helped buy land with better conditions in the higher elevations of Northwest Arkansas, which was not yet completely settled. Evidently the exploits of Henri de Tonti were well known to Father Bandini, leading these settlers to name their new town after him.

Today Tontitown is a thriving small town on the western edge of the rapidly growing metroplex of Fayetteville—home of the University of Arkansas; Springdale—home of Tyson Foods; Rogers—home of a number of manufacturing facilities of national companies; and Bentonville—home of Walmart. Tontitown is still populated with many of the descendants of those original Italian immigrant farmers, now with many others of us joining them. You couldn’t ask for a nicer more welcoming group of people, not closed off or cliquish like some small towns.

Join us in early August for our annual Grape Festival–yes, some of the Italians still grow grapes and a few even make wine–a true traditional small town festival with a big Spaghetti Supper, lots of musical entertainment, a carnival, a Queen Contest, and more. You and your kids will have a great time! (tontitowngrapefestival.com)