calsfoundation@cals.org

Yellow Fever

In 1878 and 1879, Southern cities such as Memphis, Tennessee, and New Orleans, Louisiana, were devastated by epidemics of yellow fever. Citizens of Arkansas were also affected by the disease, leading to controversial quarantine measures that prohibited travel in parts of the state and also restricted the transportation of materials such as recently harvested cotton. The creation of the Arkansas State Board of Health resulted from successful efforts to protect Arkansans from the 1879 yellow fever epidemic.

Yellow Fever (colloquially called “Yellow Jack”) is a potentially fatal virus that mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) transmit to their human hosts through their bite. It attacks the body’s organs, mainly the liver, which causes jaundice, a yellowing of the patient’s skin and whites of the eyes. The symptoms of yellow fever include headache, fever, muscle pain, and—most famously—black vomit.

Yellow fever played a small but formative role in Arkansas history when, as a result of the devastation of his army and navy in Haiti by the disease, French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte decided to sell the Louisiana Territory (which included the future Arkansas) to the United States. The first time Arkansas suffered a major recorded outbreak of yellow fever was in 1878. One of the hardest-hit towns was Helena (Phillips County), where the disease reached epidemic stage by October 15, 1878. Soon thereafter, the fever was reported in Hopefield (Crittenden County) and then Augusta (Woodruff County). There were eventually 108 cases of yellow fever reported in Hopefield, resulting in twenty-six deaths. The states of Arkansas and Tennessee ordered quarantines on travel. Being ignorant of the cause of yellow fever, and thinking the fever had arrived with shipments of cotton from the South, some areas banned all further shipments of such cotton. It was not until October 28, 1878, that the quarantine was lifted and people were allowed once again to enter and leave the state.

Dr. John B. Cummings of Forrest City (St. Francis County) later determined that the infection was possibly brought from Memphis in trading goods. Others believed that people coming from Memphis brought the disease. Fear of these supposed carriers had caused the Little Rock Board of Health to institute the yellow fever quarantine for their area, blocking all waterways and overland shipment of supplies from Memphis to within a five-mile radius of the capital.

The seeming success of the quarantine prompted the Arkansas legislature to consider a bill in the spring of 1879 to create a state board of health with power to order and enforce a statewide quarantine, but the bill failed. Regardless, a group of leading physicians who were members of the State Medical Society of Arkansas created an unofficial state board of health, with Dr. Augustus L. Breysacher as president. The summer of 1879 saw the recurrence of yellow fever in Memphis. In Little Rock (Pulaski County), the city board of health quarantined the city in response, placing health inspectors on the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad and the St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern Railroad. Travelers from Memphis had to detrain at Forrest City for inspection. Other inspection stations were placed at Jacksonville (Pulaski County), Galloway (Pulaski County), and Mabelvale (Pulaski County). However, the expense of maintaining the quarantine was straining the Little Rock treasury, and the mayor appealed to Governor William R. Miller for assistance. On August 5, Governor Miller called the acting board of health into session. The board appointed Dr. Roscoe Greene Jennings as state inspector. The board then requested that Governor Miller seek assistance from the National Board of Health, which he did and which was granted.

On August 15, Jennings ordered a mounted patrol to guard the shore of the Mississippi River for twenty-two miles above and below Hopefield to prevent any unauthorized entry. Next, the board sent a team of inspectors and doctors to Hopefield, and they disinfected nearly the entire town. While no cases occurred in Hopefield, there was a serious outbreak in Forrest City. When the word got out, the town’s population dropped from some 1,300 to seventy. By October 20, sixteen cases had been documented with thirteen deaths, including ten women dead. The last three new cases were reported on October 21. The city was strictly quarantined, and there were no reports of the disease spreading.

In November 1879, Dr. Cummings made a report to a meeting of the American Public Health Association meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, in which he praised the quarantine efforts of the Arkansas Board of Health and called for the state legislature to make the board official. The Arkansas legislature failed to act upon his recommendation. Arkansas did not have a state board of health until 1914, being the last state in existence at the time to institute one.

Yellow fever remained a local scourge. In February 1883, about 150 Jews from Russia arrived in Arkansas in order to create a commune. Malaria and yellow fever struck them, and ninety percent of their residents became ill, with eighteen to twenty dying. The following year, the surviving settlers left Arkansas for other areas of the nation. These settlers are the last known victims of yellow fever within the state of Arkansas.

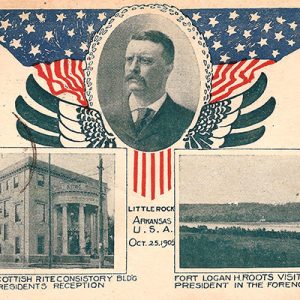

Even after the 1901 announcement of Walter Reed’s discovery that mosquitoes spread the disease, Arkansas and other Southern states were still vulnerable. In the wake of outbreaks in Louisiana and reports of people fleeing north, on August 1, 1905, Governor Jeff Davis ordered the state’s National Guard to block every major entry point into the state and to institute a quarantine preventing all travelers from the south from entering the state. There were no reported cases in Arkansas, and the quarantine was lifted in time for President Theodore Roosevelt’s visit on October 20.

Though there is no specific treatment for yellow fever, the general use of screens over windows and doors, along with programs of effective eradication of both mosquitoes and their breeding places, have prevented epidemics in Arkansas and the South. The disease continues to exist in parts of Africa and South America. Until 1996, the United States as a whole had experienced no deaths from yellow fever for eighty years, but the following seven years witnessed three deaths from the disease. All three victims had recently traveled in the Amazon region of South America. While yellow fever could return to the United States through international travelers and be transmitted by mosquitoes, current health practices and vaccines would probably prevent epidemics like those of 1878 and 1879.

For additional information:

Bell, Andrew McIlwaine. Mosquito Soldiers: Malaria, Yellow Fever, and the Course of the American Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010.

Bloom, Khaled H. The Mississippi Valley’s Great Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

Crosby, Molly Caldwell. The American Plague: The Untold Story of Yellow Fever, the Epidemic that Shaped Our History. New York: Berkley Books, 2006.

Keith, Jeanette. Fever Season: The Story of a Terrifying Epidemic and the People Who Saved a City. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012.

Public Health Reports and Papers. Vol. 5. Nashville, TN: American Public Health Association, 1879.

Scholle, Sarah Hudson. The Pain in Prevention: A History of Public Health in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Department of Health, 1990.

Josh Gann

Harding University

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.