calsfoundation@cals.org

Hate Groups

Both the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) use the term “hate group” to describe any organization that espouses hostile attitudes toward members of racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) includes people with disabilities and people with alternative lifestyles in the minority group category. Individuals who are affiliated with hate groups sometimes commit physical acts of violence or destroy property such as churches, synagogues, mosques, and other symbols associated with targeted minority groups. The historic base of white supremacist groups in the United States began with the post-Reconstruction Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which was actively involved in terrorist activities against African Americans and their supporters in the years following the Civil War. Now, the movement contains groups with varying ideologies that range from extremist religious beliefs to Southern cultural nationalism.

Although many strides have been made in the arena of civil rights for African Americans and other subordinated groups, the presence of countermovement groups such as the KKK, among others, is still an issue for Arkansas. For Arkansas and other Southern states, the KKK is a stubborn reminder of old-fashioned racism. In the early 1920s, Little Rock (Pulaski County) was home to the largest Klan group in the state. It was also the location of the national headquarters of Women of the Ku Klux Klan, though, as of 2009, it is no longer the site of any documented Klan groups. Most such groups are reportedly located in more rural areas that include Compton (Newton County), Concord (Cleburne County), Harrison (Boone County), Zinc (Boone County), and Smackover (Union County).

Klan leaders are wary of paper trails because of lawsuits filed against groups over the years, most notably the 1987 bankruptcy of the United Klans of America (UKA) resulting from legal action by the SPLC and Morris Dees. Because of the negative press and subsequent fragmentation of contemporary Klan groups, an attempt to change the image of the Klan began with David Duke during the 1980s. Pastor Thom Robb, leader of Knights of the Ku Klux Klan headquartered in Harrison, is carrying on Duke’s legacy in his efforts to sanitize the image of the Klan. Robb also sponsors a Christian Identity ministry located in Bergman (Boone County).

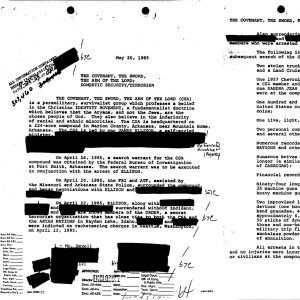

Some, but not all, Klan groups have ties with Christian Identity, an extremist religious ideology claiming that whites are the chosen people of God and all other races are inferior. Christian Identity adherents believe that non-whites will never achieve salvation and that a race war is imminent. In the Christian Identity millenarian vision, Aryan warriors emerge victorious in a new world devoid of diversity. The Covenant, the Sword and the Arm of the Lord (CSA), a Christian Identity sect located near Bull Shoals (Marion County), reportedly not only has ties with the Klan but also Aryan Nations and various other militia-style groups.

Ideas that comprise Christian Identity religious dogma were developed by Gerald L. K. Smith, who moved to Eureka Springs (Carroll County) during the 1960s, where he built a religious theme park, the focal point of which—a seven-story-tall statue of Jesus known as the Christ of the Ozarks—still stands and attracts visitors from across the country. A well-known anti-Semite, Smith had ties with an early Nazi group called the Silver Shirts. He was also instrumental in spreading racist religious doctrine through his trademark “hellfire and brimstone” sermons and political speeches in Arkansas and Louisiana.

Although not directly associated with Smith, Christian Research Ministries, another Arkansas-based Christian Identity sect, is located in Eureka Springs. Its founder, Gerda Koch, a supporter of Senator Joe McCarthy, gained notoriety during the 1960s when she accused Arnold Rose, a University of Minnesota sociology professor, of having communist ties. Her accusations resulted in a widely publicized libel suit. Prior to her death in 1994, Koch passed the directorship of Christian Research Ministries to her assistant, Dan Gentry, a Christian Identity minister. One of the primary functions of the sect appears to be the sale of customized Bibles and Christian Identity books, pamphlets, and tapes.

Kingdom Identity Ministries, located in Harrison, also serves as a clearinghouse for Christian Identity propaganda. Materials listed for sale include books and pamphlets authored by extremist religious advocates such as Pastor Dan Gayman, Wesley A. Swift, and Bertrand L. Comparet, among others. Promoted as a non-profit Christian outreach ministry, the institute sponsors a regional radio broadcast, a Bible correspondence course, a prison ministry, and a website.

American Reformation Ministries is located in Malvern (Hot Spring County). Identified as a Celtic Clan Church, the ministry uses both Klan and Celtic symbols interchangeably on its website. There is reference to a group called the Keltic Klan Kirk that appears to be affiliated with the ministry. An online disclaimer states that Keltic Klan Kirk is not a traditional Klan organization but rather a true Christian Identity church. Since several of the documented Christian Identity groups cite post office boxes rather than street addresses, it is difficult to determine if there is activity beyond selling Christian Identity literature or, in the instance of American Reformation Ministries, recruiting membership into a pseudo-Klan organization. Since extremist organizations and sects are on the periphery of mainstream society, it is not unusual for organizers to be secretive about physical addresses.

White Revolution, a neo-Nazi organization, and the Natural State Skinheads were both reportedly located in Russellville (Pope County). Since skinhead groups are often associated with neo-Nazi and fascist political ideology, the factions are sometimes linked. Adult skinheads may graduate to groups such as White Revolution and sometimes the Klan. The chairman and founder of White Revolution, Billy Roper, is a native of Morrilton (Conway County) and a former high school history teacher who prides himself on his ability to organize and recruit young people to the movement. The presence of a group of skinheads in Russellville gave him the opportunity to expand his network and continue building his organization. Both groups are now defunct. Roper later relocated to Mountain View (Stone County).

Racist groups such as the Klan have dominated the white supremacist movement since the post-Reconstruction era. More recently, nationalistic factions have emerged and serve as alternative choices for mainstream whites who do not want to be associated with Nazism, extremist religious sects, or racist groups of the past such as the Klan. One of the more stable of these groups is the League of the South (LOS), with district offices in Mammoth Spring (Fulton County) and Alpena (Boone and Carroll counties). A key issue for the LOS is achieving a free and prosperous Southern republic. Ideologically, leaders believe that the federal government is beyond reform and that the only option is for Southern states to secede legally from the Union. Also referred to as neo-Confederates, LOS factions belong to an emerging Southern cultural movement that supports ethnic and racial polarization while taking an anti-immigration political stance.

The list of hate groups in Arkansas created by the SPLC includes religious organizations such as Tony Alamo Christian Ministries, located in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and Fouke (Miller County), as well as the Nation of Islam meeting house in Little Rock. These organizations are included largely because of their outspoken opposition to other religious groups—Roman Catholics and Jews, respectively.

Monitoring hate group activity in Arkansas and other states poses challenges for watchdog groups and social researchers who study extremist ideologies. Klan groups are particularly difficult to track because of fragmentation and secretiveness of leaders about recruitment and mobilization efforts. Christian Identity sects are also elusive, and some appear to be nothing more than clearinghouses for books, pamphlets, and tapes rather than organized entities. For instance, according to the SPLC, White Revolution was relatively small and inactive, even though Roper, its founder and leader, periodically attends and speaks at white supremacist events. Some newer groups that are located in Arkansas, such as the LOS, are more ideologically subtle than the Klan and White Revolution. Leaders argue that they are not racist, and they use terms such as “secession” rather than “segregation” in group literature. Nonetheless, Arkansas is home to several sects and extremist groups that continue to undermine equality and diversity in American society.

For additional information:

Berlet, Chip, and Stanislav Vysotsky. “Overview of U.S. White Supremacist Groups.” Journal of Political and Military Sociology 34 (2006): 11–48.

“Hate Groups Map.” Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/hate-map (accessed April 18, 2022).

Jackson, Kenneth T. The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930. Chicago: Elephant Paperbacks, 1992.

Jeansonne, Glen. “Gerald L. K. Smith: From Wisconsin Roots to National Notoriety. Wisconsin Magazine of History (Winter 2002–2003): 18–29.

James Ridgeway. Blood in the Face. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1990.

Schafer, John R., and Joe Navarro. “The Seven-Stage Hate Model: The Psychopathology of Hate Groups.” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin 73 (2003): 1–8.

Dianne Dentice

Stephen F. Austin State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.