calsfoundation@cals.org

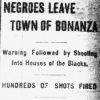

Hampton Race War of 1892

aka: Calhoun County Race War of 1892

The Hampton Race War (also referred to as the Calhoun County Race War in many sources) occurred in September 1892 and entailed incidents of racial violence all across the southern part of the county. While many sources have attributed the events in Calhoun County to Arkansas’s passage of the Election Law of 1891, with provisions that vastly complicated the voting process for illiterate citizens of all races and effectively kept them from voting, it seems that the trouble in the county started prior to the early September election.

Racial unrest was widespread in Arkansas in the 1890s, especially across the southern counties. Incidents increased after the state began passing Jim Crow legislation that limited the rights of its black citizens. (According to the Chicago Tribune’s annual tabulation of lynchings across the United States, twenty-five people were lynched in Arkansas in 1892, a number that placed the state third in the nation behind Louisiana and Tennessee.) In March 1892, the Reverend E. Malcolm Argyle reported in the Christian Recorder of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,that “there is much uneasiness and unrest all over this State among our people, owing to the fact that the people (our race variety) all over the State are being lynched upon the slightest provocation; some being strung up to telegraph poles, others burnt at the stake and still others being shot like dogs. In the last 30 days there have been not less than eight colored persons lynched in this State.”

Contemporary accounts of the Hampton Race War indicate that racial conflict erupted at least as early as March, when “white cappers” whipped a black woman for insulting a white woman. Whitecapping (or nightriding) was a form of vigilantism practiced mostly by poor white farmers and farm laborers in Arkansas and other states during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Disguised men, often members of a secret society, would employ both physical attacks and threats to intimidate their victims. In some instances, like the whipping of the black woman mentioned above, this practice was used to enforce community mores; in other cases, the causes were economic. The economic depression of the early 1890s made it especially hard for black laborers, who were resented by their white counterparts for working for lower wages. Whitecappers hoped that continued intimidation would cause black workers to leave the area, thus removing them from the labor pool.

Such incidents in Calhoun County had apparently inflamed black citizens, and they reportedly vowed to kill whitecappers. According to several contemporary sources, a white man named Unsill, described variously as a “Peoples-party man” or a Republican, as well as reportedly an ex-convict, had encouraged this retaliation (and reportedly had organized a similar action several years earlier). Tensions in the county increased at election time in early September when, according to some newspaper reports, Unsill led forty-two armed blacks to the polls, where they demanded to vote.

The first national newspaper coverage of racial unrest in the county appeared in late September. On September 21, the Richmond, Virginia, Post Dispatch published an article—based on material from the Camden (Ouachita County), Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and Little Rock (Pulaski County) papers—that attempted to sort out the various wild rumors surrounding the situation. The consensus among these often conflicting reports is limited, but all noted that there were several encounters between blacks and whites from approximately September 17 to 19, in which three to six African Americans were killed, while two whites were reportedly killed; many others were injured.

The Arkansas Gazette described an incident that probably happened shortly before September 18. Jim Harris, an allegedly “desperate negro” and leader of the disaffected blacks, apparently tried to arrest a member of his group during a church service for giving away their plans. A shot was fired, and “a general rush was made for a negro preacher, who was preaching at the time, when he escaped through the window.” The man under arrest also escaped, and the two took shelter at a friend’s home. The preacher then charged eleven people with disturbing a public worship service, and warrants were issued.

According to information from Camden, an encounter took place between blacks and whites on Saturday, September 17, near Rayford (Calhoun County). The Gazette described a similar (if not the same) encounter between a white posse and thirty blacks who had taken shelter in an old house. Reports conflict over which group fired first and how many African Americans died, with estimates ranging from two to five killed. One source, the Anaconda Standard, alleged that leader Jim Harrison (probably the same man as Jim Harris mentioned above) had been lynched. A number of black men were arrested, and they, along with the preacher, signed affidavits indicating that the purpose of Harris’s group was to kill the sheriff, the county clerk, and five other prominent citizens. The organization was county-wide, with many of its members still in hiding, and they were “making threats to kill every white man, woman and child in the county before they stop.” (Such accusations were common in many of the “race wars” of the time, including more prominent incidents like the Elaine Massacre.) Those arrested confessed that Unsill was encouraging their efforts. According to reports from Camden, another African American was killed the following night, and the county’s white citizens were back in control of the situation.

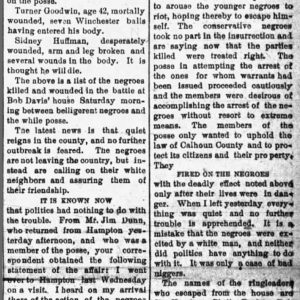

The New York Sun gave following, somewhat contradictory, report on the same date, September 21: “It was first reported that the race war in Calhoun County was due to the dissatisfaction of the negroes with the new election law, but it now appears that politics had nothing to do with the uprising. During the past two weeks several negroes have been taken from their cabins at night and severely flogged by White Caps. Charley Jones was whipped about a week ago for deserting his wife, a punishment which all the negroes endorsed. Several white men who make a living by trading with the negroes, who outnumber the whites six to one [a figure greatly exaggerated], incited them against the people of the county and, armed with guns and pistols, they immediately went on the warpath.”

According to this newspaper’s account, disaffected African Americans had been roving the county in large bands for several days, threatening every white person they saw. According to the Sun, the residents of Champagnoll Township appealed to the sheriff, who sent a Deputy James to reason with these African Americans. When the deputy and his posse arrived at their camp, blacks opened fire, wounding the deputy in the leg. The deputies returned fire, killing four African Americans. On their way back to Hampton (Calhoun County), the white posse was ambushed. They returned fire, and their attackers fled, with no casualties on either side. On Sunday, September 18, a posse met 150 mounted African Americans, only half of whom were armed. The blacks fired on the deputies for several minutes to no effect, after which the deputies charged, killing one African American and wounding seven.

According to the Sun, “On Monday [September 19] the greatest excitement prevailed in the southern part of the county. Negroes left their homes, taking only such clothing as they could carry in bundles. The cotton fields were deserted, and the farmers became much alarmed over the prospect of not being able to get their crops harvested.” The farmers reportedly exerted pressure on the fleeing black people, telling them that cholera was rampant and they would encounter it in every direction. This, coupled with powerful persuasion, caused many of them to return to their homes.

By early October, some newspapers, like the Arizona Republican, were giving yet other accounts. According to their reporting, “On the day of the conflict, a number of negroes, some of them armed, met in a church, or a schoolhouse, and it was thought by some young men that it was for political purposes. Without any warning they [the young men] shot into the meeting, hitting three men outright and seriously wounding one, who later on died. Many others were slightly wounded. Seven of the negroes were arrested and placed in the jail at Hampton. Four of them are inoffensive negroes and when taken were found to be unarmed. None of them resisted or attempted to run away….The older citizens deplore this situation, but are powerless to check the younger ones.”

There was further violence that same week when, according to the St. Paul, Minnesota, Daily Globe and several other newspapers, a “well-respected negro” who was gathering corn with two white men, was killed by two other whites. This was probably a murder of convenience, as the alleged murderers were on trial for hog-stealing, and the black man was the main witness against them. Around this same time, rumors began to swirl that enraged black residents were going to storm the jail at Malvern (Hot Spring County), where many African Americans from Calhoun County had been imprisoned. Several hundred white men stood guard at the jail one night, but the imagined raid never materialized. By October 1, papers like the Banner-Democrat in Lake Providence, Louisiana, were calling the Calhoun County race war “very short,” due to the fact that “the negro as a rule, has no disposition to antagonize the white man.”

The main incidents of the race war spanned over a month, with the major events happening in the space of four or five days. While accounts of what happened are contradictory, it is clear that the level of racial animus was high, and that at least a handful of the area’s African Americans lost their lives before it was over.

For additional information:

“Bloody Race War.” Richmond Dispatch, September 21, 1892, p. 8.

“Jail Broken Open by a Mob.” Daily Public Ledger (Maysville, Kentucky), October 19, 1892, p. 2.

“Jim Harrison.” Arkansas Gazette, September 21, 1892, pp. 1, 2.

“Race War Still On.” Daily Globe (St. Paul, Minnesota), September 25, 1892, p. 1.

“The Race War in Arkansas.” Arizona Republican, October 1, 1892, p. 1.

“Urged on by White Men.” New York Sun, September 21, 1892, p. 1.

“Whites and Blacks” Anaconda Standard (Anaconda, Montana), September 21, 1892, p. 7.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Presbyterian College

Hampton Race War Article

Hampton Race War Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.