calsfoundation@cals.org

Fouke (Miller County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 33º15’40″N 093º53’08″W |

| Elevation: | 312 feet |

| Area: | 1.36 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 808 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | May 5, 1911 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

246 |

319 |

363 |

368 |

336 |

394 |

506 |

614 |

634 |

814 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

859 |

808 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fouke is located eleven miles south of Texarkana (Miller County) on U.S. Highway 71 and Interstate 549 in Miller County. Its city limits are eight miles east of Texas and seventeen miles north of Louisiana. The city is six miles from the fertile soil of the Sulphur River and ten miles from the Red River.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In 1818, as part of a policy to lessen Spanish influence in the area, the United States built the Sulphur Fork Factory (trading post) on the Sulphur River where it enters the Red. For four years, Native Americans traded pelts, honey, and beeswax and were given in exchange flour, tobacco, blankets, guns, and other items. By 1836, with the advent of Arkansas statehood and with boundary issues and claims eased, settlers began flowing steadily into the area. Over the next half century, present-day Miller County and the towns of Rondo (Miller County), Texarkana, Bright Star (Miller County), and Fouke were established.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

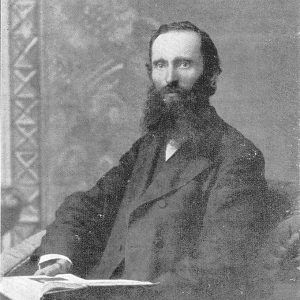

The Civil War and Reconstruction led to the movement of thousands of settlers into the western frontier. Among them was an ex-Confederate cavalryman, James Franklin Shaw, who settled in Texarkana in 1876. By 1887, he was a Seventh Day Baptist minister leading his denomination in the search for a colony location where the Baptists could enjoy privileges not available to them elsewhere. They envisioned a somewhat closed community where all business activity would cease on Saturday, which they called the Sabbath, with Sunday being a normal work and business day free from the threat of the enforcement of “blue laws.” Many Seventh Day Baptists could not gain employment because they refused to work on Saturday and/or had been fined for working on Sunday.

In 1889, they chose a site thirteen miles south of Texarkana on the Texarkana, Shreveport and Natchez Railroad, a small timber line that terminated at George W. Fouke’s sawmill two miles south on Boggy Creek. By means of a newspaper, the Sabbath Outpost, which Shaw moved from Texarkana to the site, he began to advertise the new colony. The response was quick as Seventh Day Baptists began to come to Fouke from such states as Idaho, Illinois, West Virginia, and New York. With the offer of reasonably priced land, affordable lumber, and free railroad passage to the colony, Fouke helped the Baptists build their town, which they promptly named for the Presbyterian lumberman. The streets, however, were named for prominent and nationally known Seventh Day Baptists.

Throughout its history, Fouke has had the services of multiple doctors. Dr. W. J. S. Smith came to the area in 1883 before the town began and practiced in the area until he was ninety-two. Dr. Morton Wardner, born in 1847, made his rounds in the Fouke area until he was about ninety. Drs. M. V. Newman, Jasper Joyce, and C. M. Junell also had offices in Fouke for long periods of time. As of 2012, there are no medical facilities in Fouke, given the extensive medical complex in nearby Texarkana.

Early Twentieth Century through the Faubus Era

Fouke’s population was eighty-eight in 1900 but grew rapidly. Much of that growth came from the timber and farm business and consisted of people who were not Seventh Day Baptists. With a new Texas and Pacific Railroad depot in 1906, incorporation in 1911, the oil industry boom in the 1920s, the building of U.S. Highway 71 in 1928, and increased employment of Fouke residents in Texarkana businesses, steady growth came to the town.

The Prohibition era posed sizable problems for Fouke. No less than a dozen men met violent deaths on the streets of Fouke or in close proximity between 1921 and 1936. Many of them were related to the illegal liquor traffic. The nearness of Fouke to three other states made it easy for people to commit crimes and then head for the border. Violent outlaws such as Bonnie and Clyde and Kenny Wagner hid out in the area.

The town of Fouke has dealt with a difficult social challenge throughout most of its history. During its early years, it received a significant economic boost from a small sawmill city two miles south, called Boggy (Miller County). The city, founded in 1888, consisted of 260 people, sixty percent of whom were African American, and roughly five percent foreign born. While they all lived in Boggy, they apparently worked and associated with the people settling and living at Fouke. When the huge sawmill ceased operation, the whole city of Boggy moved elsewhere, which left the area in and around Fouke with virtually no minority population.

In about 1929, a local storeowner allowed a soft drink company to place a black statue in front of his business. On several occasions during its eleven years at the location, racial epithets were hung on the statue, which made African-American visitors uncomfortable. A concerned citizen finally hauled the statue off and dumped it in Sulphur River, but Fouke’s anti-minority reputation had already been established. Rumors about African Americans being hanged in Fouke, however, have no basis in fact.

The Fouke State Bank, chartered in 1914, went broke in 1930 during the Great Depression. But Depression-era programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) put scores of men to work on such projects as roads, bridges, school gyms, outdoor toilets, soil erosion prevention, and forest preservation. The advent of World War II also provided large numbers of citizens with employment at the newly established Red River Army Depot, twenty-eight miles west in Hooks, Texas. Others took advantage of jobs opening up in Texarkana businesses and factories, which grew out of the improved area economy.

Modern Era

In 1972, Fouke and Boggy Creek, two miles south, received national attention when Charles B. Pierce produced a movie called The Legend of Boggy Creek. The movie chronicled the alleged existence of a large, hairy, red-eyed creature called the Fouke Monster. Pierce cast a number of Fouke citizens and used area wetlands, rivers, and creeks in the production. The movie premiered at the Paramount Theater in Texarkana on August 17, 1972. In 2013, the Boggy Creek Festival began in Fouke. According to the organizers, the purpose of the festival is “to bring together the local community and to share information about the sasquatch-like creature that has been sighted in the area for over a century.”

City improvements include paving of the streets in 1958; building of a city hall, jail, and fire station in 1962; installation of a new water system with deep wells in 1966; completion of a city sewer system in 1988; and the grand openings of the Community Center in 2001 and the Miller County Historical and Family Museum in 2003. Fouke Public School, built in 1902 on land donated by the town’s founder, is today the largest employer in the town. In 2011, the school had more than 1,000 students and employed 165 people. In 2004, Fouke Public School consolidated with the Bright Star School, located nineteen miles south. Bright Star was about sixteen percent African American, and the consolidation helped to move the community of Fouke away from the reputation that it once had.

In 2010, Fouke citizens dedicated the Veterans Memorial Park. Measuring two-thirds of a city block, the perpetually flagged and lighted monument contains a growing list of veterans’ names as well as brief histories of the wars.

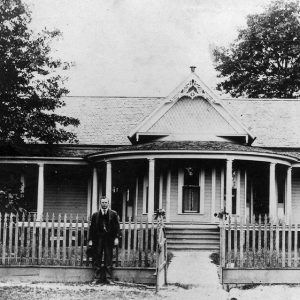

The Citizens for a Better Community, a nonprofit group, incorporated in 2007. Led by Anne Fowler, the citizens’ group has raised and invested more than $200,000 in such improvements as two highway welcome signs built on both ends of town, a digital marquee sign inside the city, a plan to beautify the city by placing flowers along streets and in front of businesses, the Veterans Memorial Park, a lunch program for senior citizens, and aid for ill or disadvantaged children and adults. In 2011, the group purchased one of Fouke’s historic homes with the plan to renovate and restore it to create an events center and community library.

One of Fouke’s more controversial periods occurred from 1998 until 2008, when Tony Alamo, a Pentecostal evangelist, bought a piece of property on the north end of town and moved in a sizable congregation that began worshiping at the Tony Alamo Christian Church. For ten years, criticism and confrontation plagued city council meetings and occupied local newspapers. Alamo, who had served time in Texarkana’s Federal Correctional Institution, was again arrested in September 2008 after his compound in Fouke was raided by federal, state, and local law enforcement personnel. He was later convicted of transporting underage girls across state lines for sex.

Notable people who have come from the Fouke area include Pearl Kinman, silent screen movie star; Harlan Robertson, raiser and developer of top bucking bulls for the Professional Rodeo Cowboy Association and the Professional Bullriders Association; and Bobby Bowen, Christian country songwriter and singer.

For additional information:

Beebe, Clifford A. Reminiscences of Seventh Day Baptist Work in the Southwestern Association. Paint Rock, AL: Bible Witness Press, 1975.

Beebe, Paul V. Seed Sown: A Study of Seventh Day Baptist Work in the Southwest. Paint Rock, AL: Bible Witness Press, 1972.

“Fouke Site of Sawmill.” Texarkana Gazette, June 27, 1976, p. 10H.

“Fouke Was Settled in Early Days by Baptists.” Texarkana Gazette, December 21, 1941.

“Many Workers Come in from Fouke.” Texarkana Gazette, August 12, 1962, p. 2G.

Miller County Historical and Family Museum. Fouke, Arkansas.

Morris, Wayne. “Traders and Factories on the Arkansas Frontier, 1805–1822.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 28 (Spring 1969): 28–48.

“Town Worries Followers of Alamo Will Take Over.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, November 23, 1998, pp. 1A, 3A.

Tyson, Carl Newton. The Red River in Southwestern History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986.

Frank McFerrin

Fouke, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.