calsfoundation@cals.org

Episcopalians

The Episcopal Diocese of Arkansas encompasses the geographic boundaries of the state of Arkansas. The diocese is composed of twenty-four self-sustaining parishes and thirty-one mission churches overseen by the Bishop of Arkansas. The bishop is assisted in pastoral work by approximately 100 ordained clergy, including priests and deacons both active and retired. In 2023, the Episcopal Church in Arkansas had approximately 13,000 members who were subsequently part of the more than 1.5-million-member Episcopal Church in the United States and the eighty-million-member worldwide Anglican Communion.

The Episcopal Church’s Beginnings in Arkansas

In 1835, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church, meeting in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, dealt with how to evangelize the American West. It established three large missionary districts encompassing all territories outside the Church’s three large territories, which extended from the Church’s establishment in the East to the Pacific Ocean. In 1838, two years after Arkansas became a state, the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Episcopal Church sent the Reverend Leonidas Polk to be the first missionary bishop of Arkansas, with jurisdiction over all parts of the United States south of the latitude 36.5° where the Episcopal Church was unorganized. This added Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) to his care and included oversight of Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and the Republic of Texas.

Arkansas’s Early Bishops

At the time of Bishop Polk’s arrival in Arkansas, there were no Episcopal churches anywhere in the state; the first service he oversaw was in a Presbyterian church. Polk organized the first Arkansas congregation of the Episcopal Church at the Little Rock (Pulaski County) home of Chester Ashley, the state’s third U.S. senator and one of its wealthiest men. The new congregation was named Christ Church after historic Christ Church in Alexandria, Virginia, which several members had attended prior to their move to Arkansas. Polk traveled throughout Arkansas on his first missionary visit, scouting out places where he believed the Episcopal Church might be established. In his reports home, he pleaded for clergymen to come to Arkansas to serve as missionaries, and in December 1838, the Board of Missions sent William Mitchell to serve as Arkansas’s first missionary, working in the Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) area. The building for Christ Church was erected in 1841–42, and the Reverend William Christopher Yeager later became the first rector. That same year, a congregation was founded in Fayetteville (Washington County).

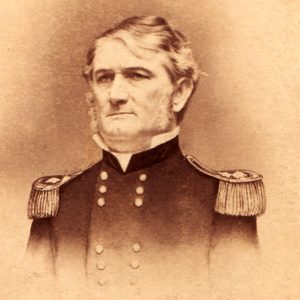

As a missionary bishop with other responsibilities, Polk only spent approximately three months in Arkansas from the time of his appointment as its bishop. In 1841, James Hervey Otey was appointed the provisional bishop of Arkansas following Polk’s transfer to the Diocese of Louisiana that year. George Washington Freeman was appointed as Arkansas’s second missionary bishop in 1844 and occupied the office until his death in 1858 (after which Otey again temporarily resumed his role as provisional bishop). By that time, the fledgling missionary diocese had grown from one congregation to seven, from just a handful of members to 400. Congregations established during this period were Trinity Church in Van Buren (Crawford County) in 1845, St. John’s in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) in 1847, St. Mary’s in El Dorado (Union County) in 1850, St. John’s in Camden (Ouachita County) in 1850, St. John’s Trinity Church in Pine Bluff in 1851, and St. John’s in Helena (Phillips County) in 1853.

The third missionary bishop of Arkansas, the Right Reverend Henry Champlin Lay, held episcopal oversight during the Civil War. Following the secession of Arkansas from the Union in 1861, the Episcopal Church in the state, which had advanced beyond missionary status, joined the Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America (CSA). After the war, Arkansas reverted to its missionary status.

The war had a devastating effect upon the Episcopalians in Arkansas, with most parishes being broken up and priests leaving the state. Bishop Lay estimated that the war turned the clock back on Church efforts some twenty years. He did, however, organize St. John’s Associate Mission School near Fayetteville, though it was only active for a few years.

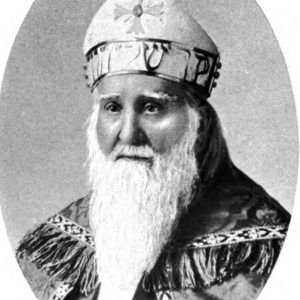

In 1869, Lay was transferred to the Diocese of Easton. The Right Reverend Henry Niles Pierce, fourth missionary bishop and the first diocesan, served from 1870 until his death in 1899. In 1871, the diocese became self-supporting and was no longer dependent on the General Convention. When Pierce began his episcopacy in the aftermath of the Civil War, Arkansas had five congregations and 605 members; at the time of his death, there were twenty-seven congregations and 3,000 members. Also during Pierce’s tenure was the establishment of an official organ for spreading missionary news. This, over time, became the Arkansas Churchman.

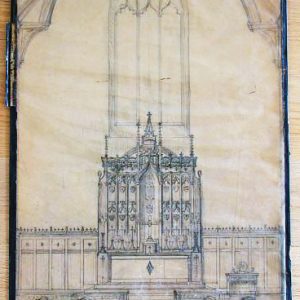

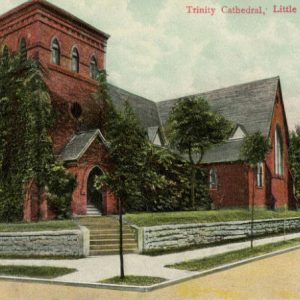

The Trinity Cathedral

One of Bishop Pierce’s great successes was the building of Trinity Cathedral in Little Rock. He said, “A cathedral does not imply a magnificent structure and great endowments. The building may be the humblest construction…but it is the Church where the Bishop has his See, and where from a center, he may carry on the missionary work of the Church.” He single-handedly procured the money necessary to build the cathedral through preaching tours on the East Coast, private gifts, and a mortgage on his home. The cathedral, which is one of the oldest of the Anglican tradition in America, was a family affair for Pierce. His son Wallace designed the building and its first furnishings; his daughter was its first organist; his wife founded the first mission of the cathedral, St. Phillip’s Church, the first African-American congregation in Arkansas; and another daughter and her husband built the St. Phillip’s Colored Mission. The cathedral was begun in 1884 and completed in 1892.

Twentieth-century Bishops

The solid groundwork laid by Bishop Pierce readied the diocese for great things at the beginning of the twentieth century, but great things were not yet to be. Under the oversight of the Right Reverend William Montgomery Brown, Pierce’s successor, the diocese saw years of over-expansion and subsequent under-funding of its work. The results were financially equal to the devastation of the Civil War.

One of Brown’s controversial innovations was his “Arkansas Plan.” Meant as a means of outreach to the state’s African-American population, it resulted in the election of a black suffragan bishop and the division of the diocese into white and black churches.

Bishop Brown resigned his jurisdiction in 1912, and in 1925, he became the first bishop in the American Episcopal Church to be deposed on the grounds of heresy after having announced in his book Communism and Christianism (1920) a conversion to “Darwinism and Marxism”; however, in the meantime, he had been consecrated as a bishop in the Old Catholic Church, a group that split away from the Roman Catholic Church after the First Vatican Council (1869–1870).

Bishop James Ridout Winchester succeeded Brown and began the process of repairing the wreckage of Brown’s tenure. World War I and the Depression of the 1930s left him with scant means of paying priests and keeping congregations open. He tightened the reins where necessary, even discontinuing publication of the diocesan newspaper, the Arkansas Churchman. He retired in 1931, having conquered many of the internal problems and achieved the goodwill of the people of Arkansas. He left the diocese stable at over 4,000 members. Winchester’s success was aided by the Right Reverend Edwin Warren Saphore—a suffragan bishop for the diocese and later its ecclesiastical authority and diocesan bishop—and the Right Reverend Edward Thomas Demby, the second black bishop in the American Episcopal Church, who was appointed as suffragan bishop for work among black communicants.

The turning point in the history of the diocese came with the 1938 election of the Reverend R. Bland Mitchell as bishop. He worked tirelessly to reverse declining membership and finances, and he came out in support of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, which mandated the desegregation of public schools. When he retired in 1956, the Church had 8,200 members, a conference center on Petit Jean Mountain (which would later be named Camp Mitchell), and a renewed spirit for establishing new congregations.

On this promising foundation, his successor, the Right Reverend Robert R. Brown, built a diocese that established St. Martin’s chapel and student center at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville, as well as created new missions in communities across Arkansas and addressed the civil rights issues emerging in the 1960s, continuing the diocese support for educational desegregation.

The tenth bishop, the Right Reverend Christoph Keller enhanced and affirmed the ministries of clergy and laity alike. In Keller’s time, Arkansas’s first female priest, the Reverend Peggy Bosmyer was ordained in 1977. This was one of the first ordinations of a woman in the national Episcopal Church following the General Convention’s approval of women’s ordination. Bishop Keller led the diocese through the changes concerning the revision of the Book of Common Prayer, lay ministry, and the role of women in the Church. Keller also oversaw the expansion of facilities at Camp Mitchell, the establishment of Sewanee Theological Education Program by Extension for lay theological education, and the establishment of Good Shepherd Ecumenical Retirement Center in western Little Rock.

In 1981, the Reverend Herbert Alcorn Donovan Jr. came to Arkansas as its eleventh bishop. During his years in Arkansas, a move was made to increase stability for congregations through the establishment of minimum guidelines for clergy salaries. New congregations were established and new buildings were built throughout the diocese. On all levels, Donovan taught the people of the diocese that the Church and its people are called to be servants to the marginalized in society. Donovan left the diocese in 1993 to become vicar at Trinity Church on Wall Street in New York City.

The Episcopal Church in the Twenty-first Century

The Right Reverend Larry E. Maze, who came from the diocese of Mississippi, became the twelfth bishop of Arkansas in 1994. Maze led the diocese in new ways in ministry for small congregations. He has also facilitated the diocese’s deeper understanding of its role as an owning diocese in the University of the South at Sewanee; the Seminary of the Southwest in Austin, Texas; and All Saint’s School in Vicksburg, Mississippi. St. Francis House, a social services agency sponsored by the Diocese of Arkansas, expanded into northwest Arkansas in the late 1990s to offer a full range of services to the growing population there; Maze was instrumental in this move.

In 1997, Trinity Cathedral established the Cathedral Middle School to build upon its successful Cathedral School, a private Episcopalian school that teaches kindergarten through the sixth grade. A high school was established in 2001. In July 2003, the school’s board of trustees changed the school’s name to the Episcopal Collegiate School. It remains the only Episcopal educational institution of high school level in the state.

Bishop Maze attracted controversy during his tenure for his support for gay and lesbian members of the Church. On September 16, 2006, the Diocese of Arkansas conducted its first blessing of a same-sex relationship; the union of Ted Holder and Joe van den Heuvel was blessed at St. Michael’s Episcopal Church in Little Rock. Such approval of gay and lesbian relationships has proven controversial, with many churches dividing over the matter.

In 2006, Maze resigned as bishop. On November 11, 2006, the Reverend Larry R. Benfield was elected the diocese’s thirteenth bishop. In 2011, the Cathedral School was closed due to poor finances. That same year, the Episcopal News Service reported that the Diocese of Arkansas, which includes fifty-seven parishes, saw a slight increase in membership and average Sunday attendance, in defiance of a nationwide decline. In 2023, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reported 13,056 Episcopalians in the state, with fifty-four Episcopal churches and missions; it reported average church attendance in 2022 of 3,074; this increased to 3.394 the following year, despite a small decline in overall membership from 12.989 to 12,956 during that same time period.

In August 2023 during a special convention at Little Rock’s Trinity Cathedral, Liberian-born John Toga Wea Harmon was chosen to serve as Arkansas’s next bishop. The Right Reverend John T. W. Harmon, fourteenth bishop of the Diocese of Arkansas, was ordained and consecrated on January 6, 2024.

For additional information:

Arkansas Episcopalian. Little Rock: Episcopal Diocese of Arkansas (1985–).

Beary, Michael J. Black Bishop: Edward T. Demby and the Struggle for Racial Equality in the Episcopal Church. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Brown, William Montgomery. Five Years of Missionary Work in Arkansas. Little Rock: Episcopal Diocese of Arkansas, 1906.

Episcopal Church in Arkansas. http://episcopalarkansas.org/ (accessed August 21, 2023).

Episcopal Diocese of Arkansas Records. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/search/searchterm/BC.MSS.10.27 (accessed October 27, 2025).

McDonald, Margaret Simms. White Already to Harvest: The Episcopal Church in Arkansas, 1838–1971. Sewanee, TN: University Press of Sewanee, 1975.

Murray, Mary Janet. “Christ Church Parochial School: Christ Church Parish and the Mission to African Americans in the Arkansas Diocese of the Episcopal Church.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2015.

Witsell, William Potsell. A History of Christ Episcopal Church, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1839–1947. Little Rock: Christ Church Vestry, 1950.

Worthen, Mary Fletcher. A History of Trinity: The Episcopal Diocese of Arkansas, Little Rock, 1884–1995. Little Rock: August House, 1996.

Michael K. McNeely

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.