calsfoundation@cals.org

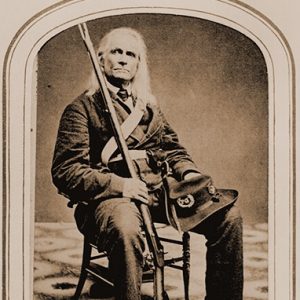

Elija Caesar Swann (1848–1919)

2014 April Fools' Day Entry

Elija Caesar Swann was a Confederate soldier who achieved national fame for his refusal to surrender to federal authorities for over three decades following the end of the Civil War. His continued military activities in the Cache River bottoms of Arkansas resulted from a very literal interpretation of the orders of his commander, Brigadier General Joseph Shelby, never to surrender to Union forces unless ordered to do so by Shelby himself.

Elija Swann was born on November 23, 1848, in rural Benton County to subsistence farmers George and LeeAnn Swann; he had ten siblings. Loyalties were divided in the Arkansas highlands, and the Swann family apparently tried to stay out of secessionist politics in 1861. However, the war came to northwestern Arkansas in March 1862 with the Battle of Pea Ridge. Foraging Union soldiers took a great deal of food from the Swann family, leaving them near starvation for the rest of the year. When Joseph Shelby began recruiting for his Iron Brigade later that year, Elija Swann joined his forces, despite being officially too young to enlist. He saw action at the Battle of Prairie Grove and then participated in the abortive assault upon Helena (Phillips County) the following year.

Where Swann made his reputation, however, was following the June 26, 1864, Skirmish at Clarendon. Two days beforehand, Shelby’s men had attacked and sunk the USS Queen City, a Union steamer. After briefly retreating from town, Shelby selected Swann for a special assignment. He informed Swann that he was to remain behind in case the Iron Brigade was chased from the area. He should engage in a campaign of sabotage if at all possible, recruiting local inhabitants into a band of irregulars who could disrupt Union traffic along the White River. Moreover, Swann was never to surrender unless personally ordered to do so by Shelby himself. According to the official report, Shelby ordered Swann to “defend the noble motherland, this soil so drenched with the sacred blood of our fathers, from the rude barbarians who violate our Southern honor and the honor of our blessed womenfolk.”

On June 26, 1864, Federal forces under Brigadier General Eugene Carr did chase Shelby’s men from the vicinity of Clarendon (Monroe County). Swann, carefully hidden, remained behind. Unfortunately for his mission, however, Swann was unfamiliar with the local terrain and proceeded up the less strategically important Cache River, which empties into the White River just above Clarendon. Apparently, as instructed, he managed to recruit a band of irregulars to his banner, as reference to a “Captain Swan” shows up in an official report pertaining to the October 16–17, 1864, Clarendon Expedition. This Captain Swan was estimated to have a force of 100 guerrilla soldiers, who had been firing upon passing boats. Union commander Captain Albert Kauffman warned locals that they would be held responsible for any harm that came to passing vessels. Official reports do not bear out whether or not this threat had any effect upon the guerrilla campaign of Swann, but Swann does not appear in further reports during the Civil War.

After the war officially ended in 1865, Swann and an ever-diminishing band of supporting troops carried out a number of actions that could, in modern terminology, be described as terrorist acts, save for the fact that Swann believed that he was still operating under the aegis of an official government. His main area of operation was the Cache River area between Clarendon and Cotton Plant (Woodruff County). He regularly fired upon steamboats, though to little effect, and managed to burn down the odd cotton compress or stave mill. However, his deeds were difficult to separate from the general lawlessness of the period, and most people thought him simply another outlaw, of which there were a number living in the rural and rough bottoms of eastern Arkansas.

Not until 1875 was anyone aware that his case was different. In June of that year, he and another man known only as Bitter Henry managed to board a steamboat, force the passengers from it, and then set it on fire as they proclaimed, “The Confederacy shall vanquish all its enemies!” Even then, Swann was imagined to be suffering from delusions brought on by mental illness. Only after a reporter from the Arkansas Gazette did some digging into the matter did the true nature of the story come to light (although the subsequent newspaper headline, “Militant Swann Strikes Fear among Locals, Wants Cache for Himself,” was widely misinterpreted).

Once Swann was understood to be waging a one-man war in the name of the Confederacy, state officials began trying to open lines of communication with him in order to convince him to lay down arms. However, Swann was difficult to find, especially as he had become skilled at evading capture and perhaps knew the Cache River area as well as, if not better than, many local residents. Officials occasionally nailed notices on trees, hoping that he would be able to read them, as well as gathered together some of his former colleagues in the Iron Brigade to troll up and down the river, hoping to attract his attention and his confidence.

All of these initiatives failed, and Swann continued his campaign of sabotage, most notably attempting to set fire, in 1889, to the Cotton Plant Academy, a coeducational school for African Americans. As historian Michael B. Dougan wrote, “Swann was far from the first Arkansan, and certainly not the last, to believe that education of the lower classes constitutes some Yankee plot against Southern manhood. Had he only had access to a newspaper, he would have known that the fight for Confederate values was continuing, not on the landscape, but in the State House.”

While Swann continued his one-man campaign of resistance to perceived Union domination, the world around him was changing significantly. Railroad lines were beginning to replace steamboats as the dominant form of transportation, and Swann, who had never seen a train before the war, believed them to be part of the Union army’s occupation forces. Consequently, he fired into railroad worker camps whenever he could. The growth of the timber industry along the White and Cache rivers was something he took personally, believing that timber workers were trying to strip the land in order to flush him out.

Locals hunting and fishing along the Cache River occasionally encountered the increasingly ragged-looking Swann and worked to convince him that the war had long since ended, but he refused to believe it and insisted that he could not surrender to anyone without the permission of Joseph Shelby, who had given him his original orders. Therefore, on April 1, 1895, an aging Shelby was taken to Arkansas, just outside of Clarendon, where he personally ordered Elija Swann to stand down.

Swann instantly went from outlaw to celebrity. This was the era in which “Lost Cause” ideology was being fashioned, and the Confederate cause was being commemorated and celebrated across the South. Swann was initially invited to speak at various United Confederate Veterans’ conventions, though his limited experience during the war coupled with his long periods of isolation meant that his discourses often veered toward the crude; his July 4, 1903, speech in Helena, titled “The Best Way to Eat Possum Innards,” was noteworthy for causing several women to faint. Many of his talks seem to have anticipated modern “listicles,” such as “Five Ways of Removing Parasitical Vermin from a Gentleman’s Nebuchadnezzar” and “Ten Means by Which One Can Avoid a Bear.” Many of his talks on survival and the military arts were collected in the print volume Swann’s Way: A Remembrance of Things Blasted, published in 1915.

By 1917, Swann was living in the Arkansas Confederate Home near Sweet Home (Pulaski County). He died on March 17, 1919, and was buried with full military honors. During the Civil War Centennial, a statue of Swann was erected in the Clarendon town square, and his legacy remains popular among Civil War re-enactors, many of whom venture out into the wilds along the Cache River each year to see how long they can endure life in the wilderness, though most of them are provisioned with coolers and bug repellant.

Horseshoe Lake, located within the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge, was renamed Swann Lake as part of the state’s sesquicentennial celebration of the Civil War in 2013. A local saloon followed suit, re-naming itself Swann Dive.

For additional information:

Christ, Mark K. I Do Wish That This Cruel Commemoration Were Over: Reflections upon Civil War Re-enactment. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Dougan, Michael B. “Duck-Duck-Swann?” Arkansas Times, March 5, 2014, pp. 13–17.

Swann, Elija Caesar. Swann’s Way: A Remembrance of Things Blasted. Little Rock: Democrat Printing and Lithograph Co., 1915.

Matthew K. Jesus

Arkansas Civil War Sesquicentennial Commission

April Fools!

Elija Swann

Elija Swann

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.