calsfoundation@cals.org

Dumas Race Riot of 1920

In January 1920, federal troops were called out to quell a feared “race war” near Dumas (Desha County). The incident is indicative of the tensions in the area at the time. World War I had deepened racial animosity in Arkansas and across the nation. African American soldiers who had served their country in segregated units hoped they would increasingly be treated and paid as equals. The area around Dumas was heavily African American, and the area around the settlement where the incident occurred was estimated to be predominately Black at a ratio of 30–1. Many white residents of such areas saw such large Black populations as a threat. Farm organizations were increasingly attempting to organize Black farm laborers, increasing whites’ fears. And the preceding summer of 1919, often called the Red Summer, had included the Elaine Massacre in nearby Phillips County. The Dumas incident made news across the nation.

According to the Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, the trouble began on January 21 when workers at a sawmill near Dumas tried to capture suspected hog thief “Doc” Haynes (sometimes referred to as Hayes or Hays). Haynes escaped but later returned to the mill with a rifle. He drove the workers, who were unarmed, into the woods. The authorities were notified, and a Deputy Breedlove and two others arrested Haynes at the nearby Black settlement. Some newspapers referred to the settlement as “Niggertown,” or “Negrotown,” and the Graphic noted: “The section between here and the Arkansas river is populated largely by negroes.” The Arkansas Gazette also reported: “The negro community….is said by officers to have been a source of trouble in the county for several years.” Included in this report was a reference to the 1911 incident in which Charles Malpass had been lynched after he and his mixed-race sons killed two police officers.

As authorities were taking Haynes to Dumas, eight or ten armed African Americans appeared and demanded that Breedlove release Haynes. Breedlove refused, whereupon the group opened fire. Haynes escaped, and Breedlove and the others returned to Dumas. Shortly thereafter, the phone lines between the settlement and Dumas were cut. Some accounts attribute this to the Black residents in the settlement, and others to local white planters, who had done something similar during the Elaine Massacre. Residents of nearby areas, including Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), were asked to assemble posses to help officials in Dumas should there be any trouble.

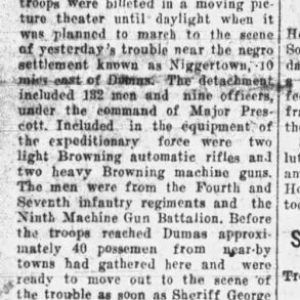

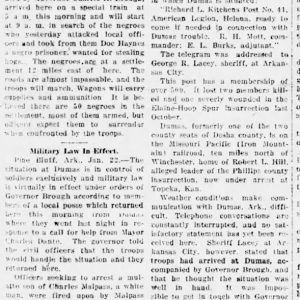

In addition, the Chicot County sheriff and the mayor of Dumas (prominent Jewish resident Charles Dante) appealed to Governor Charles H. Brough for help. On January 24, the Arkansas Democrat published parts of their plea, in which they, “knowing the strained relations existing between races here on account of the recent uprising in Elaine…earnestly desired to avoid mob law or other unlawful acts, and to secure the peace of both races.” Brough appealed to federal authorities, who authorized the dispatch of between 120 and 140 troops from Camp Pike to the area. These troops were to travel to Dumas by train and were heavily armed, including with machine guns. Accompanied by Gov. Brough, they arrived in Dumas at 5:20 a.m. on January 22.

The Hot Springs New Era is ambiguous in its description of Brough’s motives for the call-up. Part of its headline refers to Brough’s fear that events would lead to a “Dangerous Armed Conflict Between Whites and Blacks Similar to the Elaine Affair.” A later dispatch from Little Rock (Pulaski County) appended to the article reports that Brough had decided there was “no evidence of an uprising conspiracy such as was shown in investigations of the recent trouble at Elaine, Ark.,” and that he had told troops only to disarm “every man white and black in the district where the trouble originated, using force if necessary” to prevent further trouble. When the troops set out at 9:00 a.m. to go to the settlement, they met a civilian posse returning to Dumas with two of the other supposed African American ringleaders, later identified as John Welch and Frank Kibbel. They had also discovered that two others, Will and George Kibbel, had escaped along with Doc Haynes. The troops from Camp Pike then turned around and went back to Dumas and later back to camp.

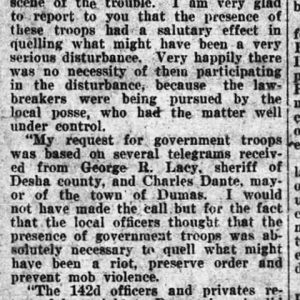

On January 24, the Arkansas Democrat published a letter that Brough had written to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, thanking him for the troops. In it, he asserted that “the presence of these troops had a salutary effect in quelling what might have been a very serious disturbance. Very happily there was no necessity of them participating in the disturbance, because the lawbreakers were being pursued by the local posse, who had the matter well under control.” He went on to explain that “I would not have made the call but for the fact that local officers thought that the presence of government troops was absolutely necessary to quell what might have been a riot, preserve order and prevent mob violence.” He referred to the incident as the “second assistance that they have rendered the state of Arkansas in quelling racial outbreaks,” the first having been the events in and around Elaine (Phillips County).

For additional information:

“Brough Sends Thanks to Baker for Troops.” Arkansas Democrat, January 24, 1920, p. 1.

“Pine Bluff Posse Rushed to Dumas after Trouble with Negroes.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, January 22, 1920, pp. 1, 6.

“Race Trouble in Desha Squelched.” Arkansas Gazette, January 23, 1920, p. 1.

“Troops Have Situation at Dumas Well Under Control.” Hot Springs New Era, January 22, 1920, p. 1.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Dumas Race Riot of 1920 Article

Dumas Race Riot of 1920 Article  Dumas Race Riot of 1920 Article

Dumas Race Riot of 1920 Article  Dumas Race Riot of 1920 Article

Dumas Race Riot of 1920 Article  Dumas Race Riot of 1920 Article

Dumas Race Riot of 1920 Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.