calsfoundation@cals.org

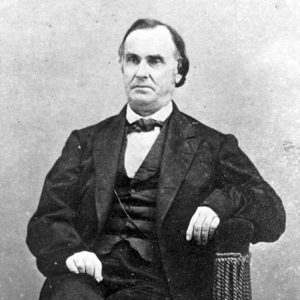

David Walker (1806–1879)

David Walker, a lawyer, a jurist, and an early settler of Fayetteville (Washington County), was the leading Whig in the state’s “great northwest” region for nearly fifty years. He began his career as a member of the convention that wrote the state’s first constitution in 1836. He chaired the 1861 convention, and remained active in politics and law until shortly before his death.

David Walker was born on February 19, 1806, near Elkton, Kentucky, to Jacob Wythe Walker and Nancy Hawkins Walker. The Walkers were a prolific and politically prominent family in Arkansas, Kentucky, and Virginia. In 1808, his father moved to Logan County, Kentucky, where in 1811 Walker first attended school. In two years, he memorized the grammatical rules of Latin. Thereafter, due largely to the family’s financial problems, his schooling was spotty, with none between ages twelve and eighteen. A badly spoiled child, he was known as “Devil Dave.” His father, “an indulgent master and poor farmer” with six daughters and two sons, lost heavily at cards on one occasion, and financial embarrassment clouded Walker’s childhood. Never did he permit even a deck of cards in his home.

Walker’s more advanced education, about eight months of instruction, was done by one of his uncles. He then went to work as a clerk for another uncle, keeping the county fee book and fulfilling part of the duties of the sheriff’s office. In the meantime, he read law, apparently on his own. His Whig politics put him in competition with his father’s legal business by taking away his clients, and that, together with a failed romance, prompted his 1830 move to Arkansas, where he was examined in law by Judge Benjamin Johnson and Judge Edward Cross. He then moved as far west as his money permitted, stopping in the newly created Washington County and settling in Fayetteville, a new town with fewer than a dozen families.

Walker scored his first legal success in a log cabin courtroom in Crawford County. The struggles of his childhood led Walker to possess an obsessive nature characteristic of Whigs; he avoided dances and parties and devoted himself to acquiring land and, later, slaves. In 1832, he was elected circuit attorney and, the next year, returned to Kentucky to marry Jane Lewis Washington; he also constructed a home in Fayetteville, now known as the Walker-Stone House. In 1834, he was reelected prosecutor and, in 1835, was elected to the territorial legislature. The next year, he was a member of the convention that wrote the state’s first constitution.

Walker’s early success attracted his impoverished relatives (including his father, who, until his death in 1838, was president of the Fayetteville branch of the State Bank), and as he later recalled, had he not been so encumbered, “the purchase of lands would have secured me a very large fortune.” By Ozark standards, Walker was rich, owning a 1,000-acre farm on the West Fork of the White River, where he raised cattle and grew wheat, corn, and apples. With twenty-three slaves, he was among the region’s largest slave owners. Walker took into his law office several young men, including Peter Van Hoose and a cousin, James David Walker.

Walker remained an active Whig until the party went defunct in the 1850s. He served as an elector for Hugh L. White in the 1836 presidential campaign. In 1840, he won a state Senate seat.

Walker’s most famous campaign was against another Fayetteville politician, Archibald Yell, in the 1840 congressional race. The charismatic Yell made short work of the reserved and dignified Walker, winning a shooting match on one campaign stop and joining a revival at another. Outside the political arena, Yell and Walker were colleagues in land speculations. Walker later wrote the text for Yell’s tombstone.

Walker reappeared in state politics in 1848 when, as part of a complex arrangement for Whig votes, the legislature elected him one of the two associate justices on the state Supreme Court, where he remained until 1855.

In 1860, Walker was a strong supporter of the Constitutional Union party’s nominee, John Bell. He opposed the summoning of the Secession Convention in March 1861 but won a seat on that body and was made president. The convention rejected taking immediate action at its first meeting, but after the firing on Fort Sumter, Walker could not resist the pressure to re-call the body. On May 4, 1861, a motion to secede from the Union passed overwhelmingly. Walker asked the five opponents to change their votes, but only four agreed to do so.

Walker’s abandonment of his Unionist sensibilities was not taken well in some quarters. After leaving Fayetteville in 1862, he accepted an appointment as colonel assigned to a Confederate military court whose death-sentence decisions raised legal issues that carried over into Reconstruction.

At the end of the Civil War, Walker returned to Fayetteville, bereft of his slaves but not his property. Walker received a pardon for his wartime activities from President Andrew Johnson that had been expedited by Governor Isaac Murphy. In 1866, after the state Supreme Court overturned a loyalty oath intended to keep ex-Confederates from voting, Walker was elected chief justice of the state Supreme Court. His most notable case, Hawkins v. Filkins (1866), sustained the legality of Arkansas’s wartime government (and hence contracts and other legal proceedings). After Arkansas (and all other Southern states except Tennessee) refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress placed Arkansas under military control. Murphy remained governor, and Walker’s court was permitted to function except in areas of civil liberties involving freed people. The creation and ratification of the Constitution of 1868 brought his term to a close.

Walker remained an important behind-the-scenes player in the tortuous course the Democrats took in the next five years of Republican rule. In 1872, he supported Joseph Brooks over Elisha Baxter for governor, in large part due to Brooks’s Liberal Republican Party promises, and continued to believe that Baxter’s party had stolen the election. In 1874, when delegates to a new constitutional convention were being chosen, Walker expected to be selected. However, a Granger revolt against taxes was also underway, and his failure to be chosen was a personal embarrassment. His return to the high court as an associate justice in 1874 came as recompense. His most important ruling, State of Arkansas v. Little Rock, Mississippi, and Texas Railway Company (1877), voided one third of the state debt, holding that the election authorizing the granting of railroad bonds was void and, hence, the bonds had never been legal. In 1876, Walker represented Arkansas at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, giving a well-received eulogistic address.

In his last years on the court, Walker’s physical and mental health declined; he resigned in 1878. His death on September 30, 1879, came after he was thrown from his buggy at the Washington County Fair. He was buried in the Walker family cemetery. Walker was one of the few Arkansans to be included in the Dictionary of American Biography (1930).

Walker was a prolific letter writer. During the Civil War, he wrote a series of autobiographical letters that reportedly covered his life up to 1865. The pages covering 1840 to 1865 were lost. His oldest son, Jacob Wythe Walker, a captain in the Confederate army, died in the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry. A second son, Charles Whiting Walker, also served in the Confederacy and survived his father. One daughter, Mary, married James David Walker. This Walker, who had served as a colonel in the Confederate army, was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1879, frustrating the comeback attempt of antebellum senator Robert Ward Johnson.

Walker’s life exemplified Whiggery, both in politics and personality, and his postwar legal acumen reflected the endurance of those characteristics even after the political party’s demise.

For additional information:

Lemke, Walter J., ed. The Life and Letters of Judge David Walker of Fayetteville: Justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court, 1848–1878. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1957.

———. The Walker Family Letters. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1956.

Smith, Ted J. “Mastering Farm and Family: David Walker as Slaveholder.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Spring 1999): 61–79.

Thompson, George H. Arkansas and Reconstruction: The Influence of Geography, Economics, and Personality. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1976.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.