calsfoundation@cals.org

Climate and Weather

Officially classified by climatologist Wladimir Köppen as having a humid sub-tropical climate, Arkansas is indeed humid, but numerous weather extremes run through the state. Humid sub-tropical is classified generally as a mild climate with a hot summer and no specific dry season. The Köppen classification is correct in that regard, but the state truly has four seasons, and they can all range from fairly mild to incredibly extreme.

The topography of the land and its proximity to the plains to the west and the Gulf of Mexico to the south play a crucial role in its climate and weather. In the United States, warm, moist air travels into the plains from the Gulf of Mexico and interacts with cool, dry air coming over the Rocky Mountains. Strong, low pressure or cold fronts can lift this moisture and quickly produce super cell thunderstorms. The flat terrain of the plains gives the inflow hardly any friction to slow down the rapid growth of these destructive storms. The state of Arkansas is a microcosm of this dynamic, with mountainous terrain in the west and flat prairie to the east.

Arkansas generally has a humid sub-tropical climate, which borders on humid continental across some of the northern highland areas. The state is close enough to the Gulf of Mexico for the warm, large body of water to be the main weather influence in the state. Hot, humid summers and mild, slightly drier winters are the norm. Fall brings the first tastes of cooler air arriving in September, but it has been ninety degrees as late as November 17. Lasting cold usually arrives by the start of November.

Winters can be harsh for brief amounts of time. Snow usually brings the state to a slow down, but an ice storm can shut it down completely. Minor ice accumulations happen somewhere in the state almost every winter, while major ice storms happen every five to ten years and can be extremely devastating. Cold but shallow air masses allow warmer, moisture-laden air to move up and over the cold air, producing freezing rain. This happens often because of the state’s proximity to the Gulf of Mexico.

The first hints of spring arrive by early March, with most vegetation reaching full bloom by early April. Winter can still cause damage to crops in April, as the latest “last freeze” of the season has happened as far into spring as May 13. Spring is also the primary severe weather season in the state. Floods and severe thunderstorms are the primary threats from March to May.

In Little Rock (Pulaski County), the daily high temperatures average around ninety degrees Fahrenheit in the summer and close to fifty degrees in winter. Annual precipitation throughout the state averages between forty and sixty inches. Snowfall is common but not usually excessive. The average is about five inches. The coldest temperature ever recorded was twenty-nine degrees below zero in the historical community of Pond, near Gravette (Benton County) in the northwest corner of the state, on February 13, 1905. The hottest temperature recorded was 120 degrees at Ozark (Franklin County) on August 10, 1936.

Despite its small size, the state has both mountains and plains. The change in landscape and altitude can cause major weather extremes, especially in the spring and fall. The highlands of Arkansas are in the northwestern part of the state. The lowlands of Arkansas lie to the south and the east. Differences in weather and climate made the lowlands more favorable for large cotton plantations with major slave populations until the Civil War, while the highland weather and climate resulted in smaller landholdings but engendered major poultry and swine production in the twentieth century.

ARKANSAS’S NATURAL DIVISIONS

Ozark Plateau

The Ozark Plateau lies in the northwestern and north-central part of Arkansas. The Ozark Plateau is an area of rugged hills and deep valleys, and is both the coolest and the driest part of the state. For example, Harrison (Boone County) has a mean January temperature of 34.9, a mean July temperature of 79.1, and an average of 45.20 inches of precipitation each year. More snow falls each winter in this part of the state than in any other.

Arkansas River Valley

Though the elevation of the Arkansas River Valley is generally lower than the Ozark Plateau to the north and the Ouachita Mountains to the south, a few mountains dot the landscape. The mean January temperature in Little Rock is 40.1, the mean July temperature is 82.4, and the average annual precipitation is 50.93 inches. The moderate climate of parts of this region allow for crops unique to this region of Arkansas, such as the wine grapes raised in Franklin County.

Ouachita Mountains

One of two major ranges in the United States that run east to west, the Ouachita Mountains receive the most rainfall in the state; the annual average precipitation in Mount Ida (Montgomery County) is 57.95 inches. The mean January temperature in Mount Ida is 37.1, and the mean July temperature is 78.5.

Mississippi Alluvial Plain (Delta)

The Mississippi Alluvial Plain lies along the Mississippi River and covers the eastern third of Arkansas. Though most of the region is level lowlands, the Mississippi Alluvial Plain is broken by a narrow strip of hills running north to south through the central plain. These hills form Crowley’s Ridge, which is a unique geological formation and one of Arkansas’s six natural divisions but is not large enough to have a significant impact on Arkansas’s weather patterns. The mean January temperature in Jonesboro (Craighead County) is 35.6, and the mean July temperature is 81.6; average precipitation for the year is 46.18 inches.

West Gulf Coastal Plain

In Arkansas, the West Gulf Coastal Plain covers the southeastern and south-central portions of the state along the border of Louisiana. Naturally, this region has the highest temperatures in the state. The mean January temperature in El Dorado (Union County) is 43.6, and the mean July temperature is 82.0; the annual precipitation in El Dorado totals 54.11 inches.

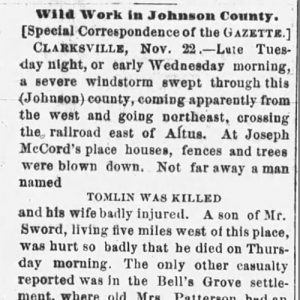

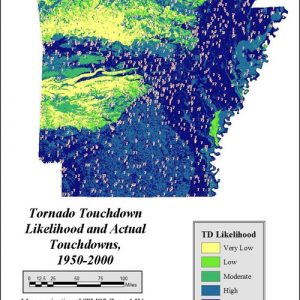

TORNADOES

On average, twenty-six tornadoes occur every year in Arkansas, but in 1999, 107 tornadoes were recorded, which remains the most ever recorded. Tornadoes can happen anywhere in the state, on land or water (the latter being called “waterspouts”). Weaker tornadoes usually do not last very long over mountainous terrain. Strong upper-level support and wind shear are necessary for any long-lived tornado. Terrain can affect very weak low-level rotations, but when the rotation is strongly rooted into the parent thunderstorm, the devastation can be tremendous.

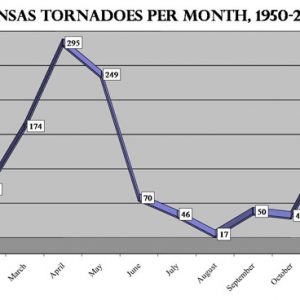

While most tornadoes happen in the spring, there is a secondary severe weather season in the fall and winter. Some of Arkansas’s most intense severe weather events or tornado outbreaks happened in the cool season. The “Super Tuesday” outbreak of February 5, 2008, killed fourteen people as the EF-4 tornado stayed on the ground for more than 120 miles through the Ozark Mountains, the longest tornado track in state history. It was also the most deadly outbreak in the state in over a decade. The Thanksgiving Day tornado outbreak of November 25, 1926, was one of the worst, with twenty-seven tornadoes and fifty-one fatalities. Two other outbreaks are worth noting. On January 11, 1898, a tornado hit Fort Smith (Sebastian County), killing fifty-five, and on January 3, 1949, a tornado that hit Warren (Bradley County) also killed fifty-five. These were the two single deadliest tornadoes in Arkansas history.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Climate.” rssWeather.com. http://www.rssweather.com/climate/Arkansas (accessed March 28, 2022).

Foti, Thomas, and Gerald Hanson. Arkansas and the Land. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

National Weather Service Forecast Office, Little Rock, Arkansas. https://www.weather.gov/lzk/ (accessed March 28, 2022).

Passe-Smith, Mary Sue. “The Death-Dealing Delta: A Climatological Viewpoint.” In Defining the Delta: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Lower Mississippi River Delta, edited by Janelle Collins. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.

Ed Buckner

KTHV-TV

Climate Change

Climate Change Derechos, Squall Lines, Downbursts/Microbursts, and "Rogue" Winds

Derechos, Squall Lines, Downbursts/Microbursts, and "Rogue" Winds Grand Prairie

Grand Prairie Science and Technology

Science and Technology Tropical Cyclones

Tropical Cyclones Weather in the Civil War

Weather in the Civil War Johnson County Weather Article

Johnson County Weather Article  Tornado Touchdown Map

Tornado Touchdown Map  Tornado Graph

Tornado Graph  Weather Station

Weather Station

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.