calsfoundation@cals.org

Chicot County Race War of 1871

aka: Chicot County Massacre

In late 1871, Chicot County was taken over by several hundred African Americans, led by state legislator and county judge James W. Mason. The murder of African American lawyer Wathal (sometimes spelled as Walthall) Wynn prompted the area’s Black citizens to kill the men jailed for their role in the murder and take over the area. Many white residents fled, escaping by steamboat to Memphis, Tennessee, and other nearby river towns. Like the Black Hawk War that occurred in Mississippi County the following year, the situation arose, in part, from a reaction to the radical wing of the Republican Party exercising its rightful power in choosing local officials. Both Mississippi and Chicot counties’ populations were primarily Black, with African Americans outnumbering whites four to one in Chicot County.

Before the Civil War, Chicot County was one of the most prosperous in the state, in terms of trade. Large plantations lined Lake Chicot, producing cotton, corn, and fruit. The devastation caused by the Civil War, combined with agricultural disasters in 1866 and 1867, profoundly affected the county’s economy, which had developed based upon the system of slavery. The county’s former slaves, after the war, were able to vote and hold office, while former Confederates were disenfranchised. Indeed, many Chicot County freedmen were active in the Republicans’ rise to power both in the county and in the state. The county’s planters backed the state’s Democrats in the election of 1868. Despite their efforts, however, the Republicans won the election.

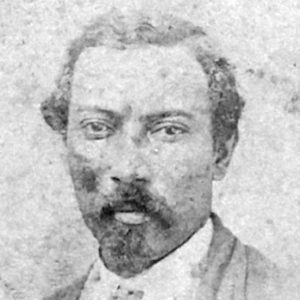

Chicot County managed to escape much of the violence that surrounded the election. The county, however, was home to the strong, well-educated politician James W. Mason, who was backed by both the governor and the Republican establishment. Mason was the son of Elisha Worthington, one of the most prominent landowners in Arkansas, who maintained a longtime and very open relationship with one of his slaves. After the war, as a free man, Mason served as postmaster of the Sunnyside Post Office (1867–1871), making him the first documented Black postmaster in the United States. He served in the Arkansas Senate from 1868 to 1869 and again from 1871 to 1872. In addition, he had helped his father to reclaim his land after the war, making him not only acquainted with the county’s people and politics, but knowledgeable about plantation operations. Mason’s abilities, as well as his charismatic personality, made him a recognized leader of the Black community in Chicot County. This made many local whites blame him for the violence that erupted in 1871.

The first reports of trouble came in late April 1871. According to an article in the Memphis Avalanche, reprinted in the Atlanta Constitution on May 5, Powell Clayton, former Arkansas governor and newly elected U.S. senator, had appointed state senator James W. Mason as the county probate judge in order to procure Mason’s support for Clayton’s state Senate candidate. Clayton later, however, named a Major Ragland (probably Major E. D. Ragland of Lee County) to the same position and instructed the Senate not to consider Mason’s appointment. Mason then returned to Chicot County and assumed office, and local African Americans forced Ragland to leave the county. In addition, the governor appointed Conway Barbour as county assessor, “ignoring the claims of all colored residents of that county.” Barbour, a former slave who had most recently been selling insurance in Lewisville (Lafayette County), had represented Lafayette and Little River counties in the Arkansas House of Representatives.

The trouble in Chicot County continued into July. According to the Galveston News, the county court met that month, and when the sheriff refused to obey an order given by Mason, Mason had him put in jail, assembled a militia, and drove Ragland and Barbour out of town. On July 17, the court met again, Ragland appeared again, and Mason “brought into town four hundred armed negroes and went for the whole crew.” At this point, Ragland left Mason in charge and went to Little Rock (Pulaski County) to confer with acting Republican governor Ozro A. Hadley. By early August, both Mason and Ragland were in Little Rock, hoping to settle the matter. Nothing had been decided, but speculation was rife that Ragland would withdraw and allow Hadley to make the decision about Mason. This apparently happened, as Mason ultimately became the county judge.

In December, the situation worsened when a Black lawyer named Wathal G. Wynn—who was, according to some sources, Mason’s brother-in-law—was killed in a Lake Village (Chicot County) store. Wynn, who was a graduate of Howard University, had been admitted to the Arkansas bar the previous September. Apparently, in early December, there was a public meeting to decide whether to appropriate money for two railroads being built through the northern part of the county. County residents were split over this expenditure. After the meeting, a Lake Village storeowner named John W. Saunders (sometimes spelled as Sanders) along with two other men, Jasper Dugan and Curtis (sometimes spelled as Carlis) Garrett, became involved in an argument with Wynn. Both Garrett and Saunders had had trouble with the Freedmen’s Bureau in the past, and Garrett had been accused of participating in an attack on the home of the local bureau agent. As tensions rose, Wynn allegedly called Saunders a liar, whereupon Saunders drew a pistol and killed Wynn. Saunders, Dugan, and Garrett were arrested and jailed.

Mason, who had dined with Wynn just before his murder, sent a letter to Ohio congressman A. G. Riddle, which was published in the Washington Chronicle and reprinted in the New York Times on December 27. He contended that Wynn had been killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan for his allegiance to the Republican Party and his efforts to “uphold the right, and to speak in behalf of the weak and needy.” According to Mason, feelings of rebellion against the federal government were at a fever pitch, and “martial law ought to be declared throughout the entire South.” The extent of actual Klan involvement in the incident has never been determined.

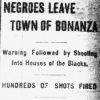

According to newspaper reports, several days after the arrest, 300 or so African Americans entered town “yelling…in a fearful manner, and driving men, women and children before them.” They went to the jail, removed the three men, took them to the woods, and shot them. Many of the area’s white citizens, fearing a reign of terror, left the area, leaving African Americans effectively in control of the town.

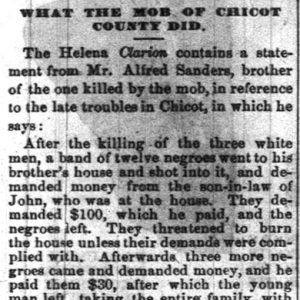

By Christmas Eve, newspapers were running dire descriptions of the situation. There were rumors that stores and homes had been looted and burned and that women had been raped. In early January, a newspaper in Bangor, Maine, quoting a dispatch from Little Rock, reported that after the killings, several groups of Black men went to John Saunders’s home demanding money, which was paid, and that the Black men then “killed all the stock of mules, horses, and cows owned by large planters in the vicinity.”

Much credence was given to the testimony of O. E. Moore of Chicago, Illinois, who, himself a Republican, was visiting the county at the time of these events. His lengthy description was published in the Memphis Daily Appeal on January 31. Describing conditions in the county, he painted what he called a “gloomy picture”: “Homes are desolated, buildings going to decay, stock all gone, lands grown up in weeds, almost every white woman in the country gone, white men afraid of their lives and getting away as fast [as] possible, every plantation for sale at a fraction of its former worth, a large portion of the little crop of cotton grown still in the fields…negroes riding in the streets and roads with their guns.” Moore blamed the radical Republicans for the trouble, and many newspapers concurred. According to the January 4 Galveston Daily News, “The instructions and advice that the Radicals have been so long industriously instilling in the negro mind are bearing their natural fruit. The outbreak at Chicot was the legitimate offspring of the advice that such men as Gov. Davis and Judge Oliver continuously give the colored people.”

Radical newspapers, on the other hand, questioned these accounts. One such paper, the Little Rock Journal, was quoted as follows in the Memphis Daily Appeal: “We learn both from the Governor and from General Reynolds, who reached here last night from Chicot, that the reports of ravishing and various other excesses reported by the telegrams, are not true. The mob have charge of the town and seem to be holding it under system. They have pressed prisoners and mules etc. into use, but otherwise have not interfered with the rights of citizens.” The governor did send his adjutant general, Keyes Danforth, to try to contain the situation. In the meantime, the sheriff had asked for Federal troops. On January 6, Governor Hadley sent fifteen members of his State Guard to Lake Village. Later in the month, 250 federal troops were sent from New Orleans, Louisiana. Although these troops remained only a short time, they helped to achieve an uneasy peace in the county. The governor’s guards remained in Chicot County until late April.

On February 9, the Memphis Daily Appeal reported that the sheriff was attempting to arrest Coroner Wesley Brown. Brown, who had supposedly waved his pistol in the face of John Saunders’s wife, had fled into Mississippi. He gathered forty supporters, returned to Chicot County, found a “timorous or corrupt” magistrate, and demanded to be tried. Mrs. Saunders had fled, and, given that no witnesses were willing to appear, Brown was acquitted.

By April 1872, tensions had apparently abated in the county. Brown had been tried for theft by the circuit court and sentenced to five years. There continued to be some political bad blood, this time between Mason and Barbour. In late August 1872, both were at what the Memphis Daily Appeal dubbed the “Claytonite” convention or the “Convention of the Minstrels” in Little Rock. Each was hoping that his delegation would be seated at the convention; speculation was that Barbour’s group had the better chance.

Mason, despite these tumultuous events, retained his political power. He was elected county sheriff in November 1872. The days of Republican ascendancy, however, were coming to an end. In March 1873, the state legislature crafted a constitutional amendment which would grant political rights to all ex-Confederates. The voters approved the amendment, thus opening up the probability of a return to Democratic rule. Mason was eventually tried for his participation in the Chicot events. After a trial of several weeks, he was released on a writ of habeas corpus. He died of unknown causes in 1874. As late as 1883, almost all of the elective offices in Chicot County were held by African Americans.

For additional information:

“Arkansas. The Claytonites’ Convention at Little Rock—The City Full of Dirty Workers—Signs of the Political Zodiac.” Memphis Daily Appeal, August 20, 1872, p. 9.

“Arkansas.” Bangor Daily Whig and Courier (Bangor, Maine), January 3, 1872, p. 3.

“Arkansas: Given over to African Barbarism.” Nashville Union and American, February 10, 1872, p. 11.

“Arkansas…The Horrors of Chicot Revived.” Nashville Union and American, February 7, 1872, p. 1.

“The Arkansas Troubles.” New York Times, December 27, 1871, p. 1.

“The Arkansas Troubles: Emphatic Denial by the Governor—A Singular Narrative of Events as Given by an Eye-Witness.” New York Times, December. 29, 1871, p. 2.

“Bloody Chicot.” Arkansas Gazette, February 10, 1874, p. 1.

“Chicot.” Memphis Daily Appeal, March 2, 1872, p. 2.

“Chicot County.” Arkansas Gazette, February 4, 1872, p. 1.

“Chicot: The Bloody Riot—Effect of the News in Little Rock.” Memphis Daily Appeal, December 25, 1871, p. 17.

DeBlack, Tom. “A Garden in the Wilderness: The Johnsons and the Making of Lakeport Plantation, 1831–1876.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1995.

“Effect of Radical Teachings.” Galveston Daily News, January 4, 1872, p. 2.

“Jehorum Jumper.” Memphis Daily Appeal, February 9, 1872, p. 2.

“A Little Negro Rebellion and How Clayton Brought it About.” Atlanta Constitution, May 5, 1871, p. 2.

“Murder and Pillage by Armed Negroes.” Edgefield Advertiser (Edgefield, South Carolina), December 28, 1871, p. 2.

“Negro Militia in Arkansas.” House Ex. Doc. no. 209 s 42 Cong., 2 Sess., p. 23. Report of T. W. Morrison, 2nd Lieutenant, 16th Infantry, U.S. Army [January 29, 1872]. In Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Vol. 2, edited by Walter L. Fleming. Cleveland, OH: Arthur H. Clark, 1907.

“Our Great Calamity.” Memphis Daily Appeal, January 31, 1872, p. 1.

Schnedler, Jack. “Uproar in Chicot County.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 5, 2021, pp. 1H, 6H. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/05/uproar-in-chicot-county/ (accessed November 19, 2025).

Untitled article. Memphis Daily Appeal, August 2, 1871, p. 13.

“What the Mob of Chicot County Did.” Arkansas Gazette, January 3, 1872, p. 1.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.