calsfoundation@cals.org

Camp Joseph T. Robinson

aka: Camp Pike

aka: Camp Robinson

Camp Robinson in North Little Rock (Pulaski County) is home to the Arkansas National Guard and is the principal training area for the Arkansas Army National Guard. It is also used by a number of other military and civilian agencies.

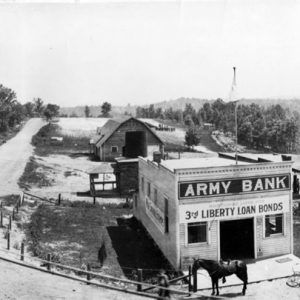

The forerunner to Camp Robinson was known as Camp Pike, named in honor of General Zebulon Montgomery Pike. The camp was awarded to the central Arkansas area due to the efforts of the Little Rock Board of Commerce. The board offered, at no cost to the U.S. government, the purchase and lease of the lands needed to establish the post. Little Rock (Pulaski County) was awarded the camp on June 11, 1917, and the money needed to fulfill the promises was raised from public donations. A total of $500,000 was raised—the equivalent of over $5 million in year 2000 dollars.

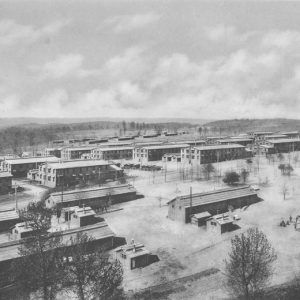

Construction began in June 1917 and was substantially completed in November of that year. Over 10,000 workers were employed in the construction of the camp. The construction quartermaster for the camp was Arkansas native Major John Fordyce. Construction costs totaled about $13,000,000.

Originally the home of the Eighty-seventh Division, the post served as a replacement training facility after the division deployed to France and then as a demobilization station and home for the U.S. Third Infantry Division after the war ended. In 1922, the 6,480 acres of land owned by the United States was deeded to Arkansas with two provisions: that it would be used primarily for military purposes and that the United States could reclaim the land if needed during an emergency.

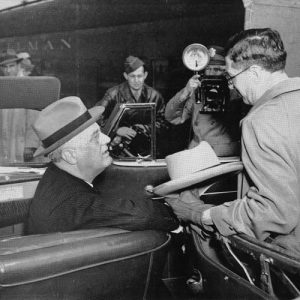

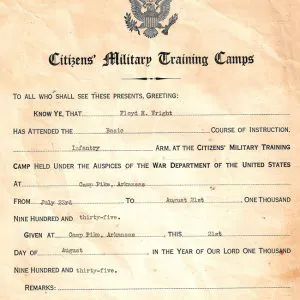

During the time between World War I and World War II, the post served as the headquarters of the Arkansas National Guard. Facilities to support the use of the post in this capacity were funded by sales of unneeded materials from the original camp. In addition, a large Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) unit was stationed on the post, and the post hosted Citizen’s Military Training Camps (CMTC) each summer. Future president and then-colonel Harry Truman commanded the 1933 CMTC. In 1937, Camp Pike was renamed for the late U.S. senator Joseph Taylor Robinson of Arkansas.

In early 1940, the United States reclaimed the post and began construction on a temporary cantonment for the Thirty-fifth Division, a National Guard division being called to active duty for one year of training. Elements of the Thirty-fifth began arriving in early January 1941. Called to active duty for one year, the Thirty-fifth was scheduled to be released from active duty on December 23, 1941.

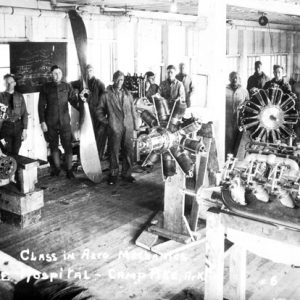

With the start of World War II, the post took on a new role as a replacement training center. Initially, there were two centers, one for basic training and the other for medics. In 1944, the two were combined into the Infantry Replacement Training Center.

In addition to its role in training soldiers, Camp Robinson also housed a large German prisoner of war facility, with a capacity of 4,000 prisoners.

The post was Arkansas’s second largest city, with an average daily population of about 50,000. An estimated 750,000 soldiers had trained at Camp Robinson when training ended in 1946 and control of the camp, which had grown to 32,000 acres, reverted to the State of Arkansas.

Portions of Camp Robinson were given to other organizations that demonstrated a need to the U.S. government. The wildlife management area (WMA) north of Highway 89 and the land where the North Little Rock airport is located were early examples. A more recent instance was the re-designation of several hundred acres in the southeast corner of the post as a place to consolidate central Arkansas’s army, navy, and marine corps reserve centers. In honor of the original name of the post, this area is now known as Camp Pike. Most recently, land was designated for use as a National Cemetery.

Camp Robinson continues to serve as the home for the Arkansas National Guard’s Joint Forces Headquarters and other Arkansas National Guard units. It is also the home of the National Guard Bureau’s Professional Education Center and Marksmanship Training Unit.

For additional information:

Arkansas and the Great War: Camp Pike. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Video online at http://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15728coll5/id/978/rec/1 (accessed February 9, 2023).

Arkansas National Guard Museum. http://www.arngmuseum.com (accessed February 9, 2023).

Black & Veach, Inc. “1941 Completion Report, Camp Robinson.” Archives. Arkansas National Guard Museum, North Little Rock, Arkansas.

Camp Pike Newspaper Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Fordyce, John. “Camp Pike Completion Report.” 1917. Archives. Arkansas National Guard Museum, North Little Rock, Arkansas.

Hanley, Ray. Camp Robinson and the Military on the North Shore. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

Nieser, Tracy. “The History of Camp Pike, Arkansas.” Pulaski County Historical Review 41 (Fall 1993): 64–71.

Panamerican Consultants, Inc. “Archaeological Investigations at the POW Camp at Camp Joseph T. Robinson, Pulaski County, Arkansas.” March 2005. Archives. Arkansas National Guard Museum, North Little Rock, Arkansas.

Polston, Mike. “‘Dear Home Folks’: The Camp Pike Letters of an Iowa Sammy in the Great War.” Pulaski County Historical Review 62 (Fall 2014): 70–76.

———. “Letters from Camp Pike: Walter C. Yeager.” Pulaski County Historical Review 65 (Spring 2017): 20–25.

Razer, Bob. “Camp Pike and the Great War: A Pictorial Essay.” Pulaski County Historical Review 65 (Spring 2017): 11–19.

Ratermann, Travis. “A Week of Tragedies: Two Camp Robinson Battalions Overcome Accidents to Help in the World War II Effort.” Pulaski County Historical Review 68 (Spring 2020): 2–11.

Screws, Raymond D. “‘To Carry Forward the Training Program’: Camp Pike in the Great War and the Legacy of the Post.” In The War at Home: Perspectives on the Arkansas Experience during World War I, edited by Mark K. Christ. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Steve Rucker

Little Rock, Arkansas

The U.S. Air Force used the camp for several months in 1955, until the new air base barracks could be constructed. I was quartered there from August to October until the Jacksonville barracks opened in Oct. 1955. We lived in the WWII huts, four to a hut, no glass windows, only shutters, with gang showers in a cinder-block building. We commuted by bus every day to the air base. The commander was a West Point grad named Curtis. I think that he was a captain. One memory that I have is that the jukebox in the rec room still had the WWII songs in it, the big band music. In our hut were initials and names carved into the wood of soldiers headed out to war. I often wondered how many never came back. I have a special place in my heart for the old Camp.

My first name came from Onis Franklin, MD, and according to local records he spent some time at Camp Pike during WWI as an army doctor with the rank of lieutenant. He returned to Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, and practiced for sixty-three years.