calsfoundation@cals.org

Button Blank Industry

America’s mother-of-pearl button industry boomed in the late 1800s due to a seemingly inexhaustible supply of freshwater mussels, the bounty of Mississippi River Valley tributaries. Long made from saltwater marine shells, pearl buttons could now be made from freshwater shells due to new engineering techniques. In addition, the 1890s McKinley tariff on imported goods protected the market for American button makers, allowing mother-of-pearl button manufacturing to explode.

Button finishing plants in Iowa and New York were supplied by tons of button blanks—a circular piece punched out of a shell before the smaller thread holes were added, similar in shape and size to a coin—that came from small factories lining the northeastern Arkansas rivers, which teemed with the freshwater mollusks that naturally grew mother-of-pearl-lined shells. Supplying the button blank factories with raw material offered farm families extra income because shell harvesting fit around the ebb and flow of agriculture. Some families worked together—the men hauling the mussels from the river and the women and children steaming them open, discarding the animal flesh back into the river for fish food, drying and sorting the shells, and keeping an eye out for pearls.

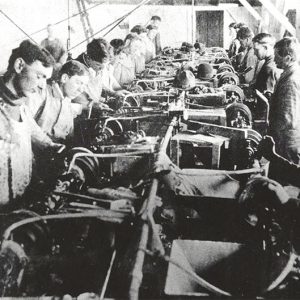

Some button blank operations consisted of a single man, while other factories employed as many as sixty workers. Factories, which had to be close to a railroad for shipping outbound cargo, had button-cutting machines with variously sized tubular saws that generated small to large button blanks. Coal or propane, and eventually electricity, powered the machinery. The shells were softened by soaking in water prior to drilling, and this necessitated water towers in some locations. A few factories had grinding capability, pulverizing spent shells into agricultural lime or meal.

Button factories on the White River were located in Batesville (Independence County), Newport (Jackson County), Grand Glaise (Jackson County), Des Arc (Prairie County), DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), and Clarendon (Monroe County). Oil Trough (Independence County), Akron (Independence County), Newark (Independence County), and Augusta (Woodruff County) are also mentioned. The Black River factories included Corning (Clay County), Pocahontas (Randolph County), and Black Rock (Lawrence County). Operations were also located in Brinkley (Monroe County) and Parkin (Cross County). Some businesses started in this region and were later bought by out-of-state corporations, resulting in an outflow of profits and some confusion regarding names; for example, an Iowa company might own the plant, but it was referred to locally as the Black Rock Button Factory.

Batesville saw two waves of button blank factories. The first, at the turn of the twentieth century, was located in Poke (or Polk) Bayou near the present-day jail. The second, a 1940s location, was situated near the Missouri Pacific depot with two factories, one with ten to twelve machines and the other a solo operation.

Newport was a major hub in the button industry due to its proximity to the river and railroad. A factory was listed in Chastain’s Addition as early as 1902. Jackson County 1907 deed records indicate a plant in the Morris Addition next to Maple Avenue, between Morris and West 2nd streets. Factory names included Rockport, Chalmers, and Newport Pearl Button Company. In 1940, the Newport Chamber of Commerce stepped in to try to save the industry, which was taken over by the Muscatine Pearl Works of Muscatine, Iowa, in 1941. Leon Ragan was still making buttons in a shop behind his house in 1958.

A factory in Newark was located on Oak Street between Front and 2nd Streets. Grand Glaise had a four- to five-machine plant in the 1940s.

Arkansas State Archives records for DeValls Bluff mention a button factory as early as 1896 and its subsequent purchase by the Erie Pearl Button Company. The Chalmers Button Company bought and reopened the factory, located approximately one-half mile northeast of the post office, which was last owned by the Rockport Pearl Button Company of Indiana. This operation had fifty-seven saws, the largest number for that time period. The plant was also listed as the DeValls Bluff Pearl Button Co.

Clarendon had the Keithsburg Pearl Button Factory, later the Rockport Pearl Button Company, by 1907, near 7th Street just down from Monroe Street. A second location from the 1940s was down from the courthouse toward the levee.

By 1914, Corning had the Black River Button Company located northwest of the Booser Saw Mill alongside the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad between Pine and Olive streets. Around 1927, the Wisconsin Pearl Button Company’s Dixie Plant was located across the railroad tracks from 1st Street, between Market and Chestnut streets. It was also listed as the Corning Novelty Co.

By 1922, Pocahontas had a factory across from the depot of the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad. In 1941, a new factory was set to open between the Frisco tracks and Black River. Factory names for this second wave included the Clarendon Pearl Button Factory and the Pocahontas Pearl Works, owned by the Muscatine Pearl Works.

Black Rock’s factory formed in 1900, began output in 1901, shut down due to a labor strike, and was purchased by a Davenport, Ohio, company. Harvey Chalmers Pearl Button Company, based in Amsterdam, New York, operated at two factory locations in Black Rock. By 1914, the Rockport Pearl Button Company was located between Falls Creek and the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad track spur.

Brinkley, at the nexus of two railroads, had a button factory at 301 North Grand Avenue, and names for operations included Brinkley Pearl Works and Muscatine Pearl Works. The Parkin Button Company, on the St. Francis River, employed fourteen men.

The initial demand for buttons in the first two decades of the twentieth century suffered setbacks in the Great Depression as new clothing purchases diminished. During World War II, government restrictions on zippers and other metal garment closures (to save metal for the war effort) reinvigorated the button industry, and demand again rose for Arkansas shells. After the war, metal could be used again and other materials for fasteners gained popularity, including plastic. Demand decreased and the factories closed, although some solo operations lingered. Today, little remains of the industry but the occasional telltale sign spotted on the ground—shells laced with perfectly round holes—and millions of mother-of-pearl buttons saved in button jars across the country, cut from blouses and shirts from a time when nothing was wasted.

For additional information:

“Industry.” Arkansas WPA Research Files. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

McLeod, Walter E. Centennial Memorial History of Lawrence County. Russellville, AR: Russellville Printing Company, 1936.

Morgan, James Logan, ed. Centennial History of Newport, Arkansas 1875–1975. Newport, AR: Jackson County Historical Society, 1975.

Robertson, Irene. “Interview with John Dimlar.” Prairie County Federal Writers’ Project Papers, Folder 3. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Shiras, Tom. “Women Using Fewer Buttons; Arkansas Shell Diggers Hit.” Arkansas Gazette, July 21, 1940.

Stewart, Glynda. “Black Rock Pearling and Button-Cutting Industry.” Lawrence County Historical Quarterly 1.4 (1978): 5–9.

Stockard, S. W. History of Lawrence, Jackson, Independence, and Stone Counties of the Third Judicial District of Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Democrat Company, 1904.

Lenore Shoults

Mountain View, Arkansas

I find all this information fascinating! I would love to get a copy of Lenore Shoults’s book Mother-of-Pearls: The Entwined History of Shell and Pearl in Arkansas.