calsfoundation@cals.org

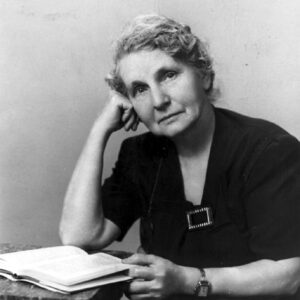

Bernie Babcock (1868–1962)

aka: Julia Burnelle Smade Babcock

In 1903, Julia Burnelle (Bernie) Smade Babcock became the first Arkansas woman to be included in Authors and Writers Who’s Who. She published more than forty novels, as well as numerous tracts and newspaper and magazine articles. She founded the Museum of Natural History in Little Rock (Pulaski County), was a founding member of the Arkansas Historical Society, and was the first president of the Arkansas branch of the National League of American Pen Women.

Bernie Smade was born in Union, Ohio, on April 28, 1868, the first of six children, to Hiram Norton Smade and Charlotte Elizabeth (Burnelle) Smade. The Smades raised their children with a freedom uncharacteristic for that time. When Smade’s lively imagination was mistaken for lying and she was expelled from kindergarten, her mother said, “Oh, that’s only a sign she’ll be a writer when she grows up.”

Her family moved to Russellville (Pope County), where Smade attended public school. On March 17, 1884, when she was fifteen, she read her impassioned essay at the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) Convention, which was published by request of the Russellville WCTU. She enrolled in Little Rock University, paying her way by working as the college president’s housekeeper.

Although she made excellent grades in school, Smade did not return to college the next year but instead married William Franklin Babcock, who worked for the Pacific Express Company, in 1886. For a short time, the couple lived in Vicksburg, Mississippi, where the society that had relied heavily on slavery in the recent past still retained many of the attitudes and customs of that time. Her observations there resulted later in the play Mammy, the first drama in which a slave “mammy” plays the leading role; it was later published by Neale Publishing Company of New York.

The Babcocks returned to Little Rock, where, after eleven years of marriage and the birth of five children, William died. His widow was determined to make a living by writing so that she could stay at home and raise her family; at night, she wrote stories and poems that she sent to editors across the country.

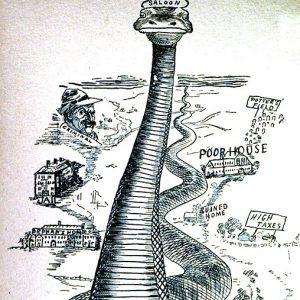

Her first book, The Daughter of the Republican, was published in 1900 and sold 100,000 copies in six months. It was followed by The Martyr (1900). These were “temperance novels,” describing the suffering caused by the consumption of liquor. Her books and emotionally charged tracts on the subject were credited with helping to bring about the national prohibition amendment in 1920.

Justice to the Woman (1901) and A Political Fool (1902) were political novels also about temperance. By Way of the Master Passion touched on the “fascinating story of evolution.” Babcock herself was interested in nature, and Darwin’s Origin of Species and the Bible were the first two books in her library after she was married.

When her youngest child started school, Babcock became society page editor for the Arkansas Democrat. She wrote features and, for a while, was the main editorial writer for the paper, though without a byline, which was standard newspaper practice at the time. Babcock was also the first female telegraph editor in the South.

After five years at the Democrat, she resigned to start her own project, becoming editor and publisher of the Little Rock Sketch Book, “the most beautiful magazine in the South,” whose photography, paintings, stories, poetry, and music were original Arkansas contributions. The quarterly magazine started in July 1906 but came to an end in 1910 when Babcock announced her plan to move to Chicago. In 1908, she also published the first anthology of poetry written by Arkansans, Arkansas People and Scenes: Pictures and Scenes, containing 100 poems and seventy illustrations.

Babcock moved to Chicago to work for a newspaper there, which serialized several stories she wrote, including “Daughter of the Patriot” and “The Devil and Tom Walker.” She also served on the staff of The Home Defender, a prohibition newspaper. She later returned to Arkansas, believing that to be a better environment for raising her children.

Babcock spent winters in New York City doing research in libraries and in the National History Museum. Her study of “submerged poverty people” (the unrepresented or unacknowledged poor) was introduced at a meeting of garment workers. It was used to inaugurate a strike for higher wages. Before the strike ended, 75,000 sympathy strikers marched on Broadway.

After reading a story in Ladies’ Home Journal about the love affair of Abraham Lincoln and Ann Rutledge, Babcock corresponded with the Illinois Historical Society and many persons who had known Lincoln personally. She became one of the country’s leading authorities on Lincoln, having conducted numerous personal interviews with his law partners and others, and published of The Soul of Ann Rutledge in 1919. This biographical novel was an international success, going through fourteen printings and translation into several foreign languages. It also was adapted into a stage play in 1934 and a radio play in 1953, when it was performed by the American Theater Wing.

Babcock learned through her research that she shared many of Lincoln’s beliefs, and she wrote four more books about Lincoln and his family between 1923 and 1929. She also wrote Light Horse Harry’s Boys (1931) about Robert E. Lee and The Heart of George Washington (1931) about the first U.S. president.

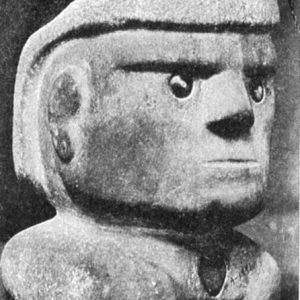

She used her love of nature and history to repudiate noted polemicist H. L. Mencken’s derision of Arkansas. Babcock decided in 1927 to “show ‘em by establishing a quality museum to belie the state’s reputation as a cultural backwater.” She first presented exhibits in a storefront on Main Street in downtown Little Rock. One such exhibit was King Crowley, a sculpted stone head containing eyes of copper with silver pupils and ears decorated with gold plugs, which had been “discovered” in a gravel pit on Crowley’s Ridge in Craighead County; thought to be an ancient artifact, it was later proven to be a fake, though Babcock was long a proponent of its authenticity.

Later that year, she secured the third floor of City Hall for the fledgling Museum of Natural History and Antiquities, which she financed with donations from friends. In 1928, Babcock wrote to Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the New York Natural History Museum, asking for help in securing exhibits. He sent her a boxcar of mounted animal displays.

In 1933, when space was needed for Works Progress Administration (WPA) offices, the museum’s exhibits were crated and stored in the basement. Many of these artifacts were pilfered, and few were returned despite Babcock’s call for help to the mayor.

In 1935, Babcock became folklore editor of the Federal Writers’ Project, for which she did research on African-American and Native American history in the state. Surveys included interviews with almost 1,000 ex-slaves, at which time she attended all-night voodoo rituals in keeping with her interest in the supernatural. She wrote for Modern Mystic, a magazine in London, England, and was a member of both the American and British Psychical Research Societies.

By 1941, the last surviving Confederate soldiers of the Civil War had vacated the Arsenal Building in Little Rock City Park. With the help of businessman Fred Allsop and the promise of city government to provide a curator’s salary and funds to renovate the building, Babcock again opened the Museum of Natural History. Then in her seventies, she literally lived in the basement and often scaled ladders to paint murals of prehistoric scenes on the walls to enhance exhibits.

Thanks in part to Babcock’s influence, the city park was renamed in honor of General Douglas MacArthur, who had been born in the Arsenal Building. Babcock corresponded with MacArthur, and he and his family attended a ceremony at the park on March 23, 1952.

Babcock retired from the museum in 1953. She donated many objects to the museum, including the large marble statue of a woman, entitled Hope, which she had placed there in memory of her husband. She itemized other items and billed the museum $800, with which she planned to start a new life at the age of eighty-five.

Her new life began in a small house on top of Petit Jean Mountain, where she began to paint and continued to write. In 1959, she published her only volume of poetry, The Marble Woman. She died at home on June 14, 1962, a few weeks after her ninety-fourth birthday; a neighbor found her sitting with a manuscript in her hand. Her mountaintop retreat had been aptly named—Journey’s End. She was buried in Oakland Cemetery in Little Rock. In 2024, she was inducted into the Arkansas Women’s Hall of Fame.

For additional information:

Baker, Mrs. Albert E. “Bernie Babcock Made Notable Contributions to Literature—And History.” Arkansas Gazette, July 22, 1962, p. 4E.

Bernie Babcock Collection. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Bernie Babcock Remembrances. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Camp, Marcia. “The Soul of Bernie Babcock.” Pulaski County Historical Review 36 (Fall 1988): 50–62.

“Nationally Noted Author, History Museum Leader Dies at Petit Jean Home.” Arkansas Gazette. June 15, 1962, p. 11B.

Pyron, Netta F. “Bernie Babcock, A Twentieth Century Sentimental Novelist.” MA thesis, Iowa State University, 1971.

Teske, Steven. Unvarnished Arkansas: The Naked Truth about Nine Famous Arkansans. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2012.

Marcia Camp

Little Rock, Arkansas

In 1936, my father was working as a field supervisor for the Writers’ Project. One of his assignments was the Arkansas Project, where Bernie Babcock was the state’s project director. These are excerpts from my father’s letters that pertain to Babcock. You will see that he wasn’t initially impressed with this woman who was more than twice his age, but he had changed his view by the time he finished in Arkansas.

Feb 3, 1936: “It was sweet to have your train-to-Atlanta letter, which came this morning from Jackson & due to press of business I have treasured it in my pocket all day before reading it.

“Mrs. Bernie Babcock, the State Director here, wrote ‘The Soul of Ann Rutledge’ & other books. You may have read it at some time or other. She is a sturdy picturesque oaklike old lady, young in spirit, with colorful rural use of words, as for instance, ‘recommend’ for ‘recommendation.’ It didn’t take long to find that she was a dry & a few other idiosyncrasies, tho on some points she is very advanced—a liberal of the Jane Addams school.”

Mar 24, 1936: “I spent the morning dictating a long report on Tennessee, & the afternoon having Mrs. Babcock show me things. God! She is a garrulous and tiresome old woman! By 4 o’clock I had all I could stand and left. Came home & took a nap to recover. Tomorrow morning I’m having an editorial conference, and tomorrow evening I aim to get away to Jackson. This place is utterly unbearable. Mrs. B. went to New Orleans to the conference Baker called—the one Wallace Miller attended. She feels very superior to the other states. It’s hard to live around her.”

Sept 28, 1936: “I got into Little Rock practically suffocated on a stuffy train. The only bit of loveliness so far was a flock of geese I saw going over the city in precise military formation just as the train was coming into town.

“What seems to have happened to bring me here, so far as I can tell, is that Clay Fulks, who was put in here by Frank Wells to do the job, wrote to Frank how things were going here, and I being nearest (Frank is apparently out west, the lucky stiff) was brought to Ark. again.

“Bernie is rushing to complete stuff by Oct. 1 and says she will do it. This relates to Tours, Cities, Points of Interest, and maps. But the darned old fool has Fulks and Charles J. Finger, her only capable writers (put on by Wells), slaving away on Introductory Essays, which are not due at any time yet specified.

“I loaded myself up with copy to go over tonight. I have already found some of it bad enough to justify issuing a memorandum tomorrow morning that ‘all copy intended for Washington must pass over the desk of Clay Fulks, Editor-in-Chief, for final approval before being routed to Washington,’ or words to that effect. I’ve passed the point where the old lady can talk my ear off and so put me to sleep.

“Maybe I’ll have a little fun in the end, for I’ve made up my mind she won’t load Washington with a lot of tripe just to say she met the deadline.”

Sept 29, 1936: “Then I went over to see Dot Kennon, director of Women’s & Professional Projects, who it a refreshing person and very humorous, in order to let the strength of the memo to sink it. Pretty soon Mrs. Babcock called; Mrs. Kennon said to tell her she was in conference. She came and waited, and then when we had about decided to let her in, she was not to be found. Then Floyd Sharp, the administrator, wanted to see us. Bernie had taken her troubles to him. There was news that he had countermanded my order.

“Dot took me for a drive at noon to see park, etc., around Little Rock. After lunch we went in to see Sharp.”

“Sharp I find to be a person of delightful humor and a very keen person. In all we spent two hours with him. It developed that Frank Wells had agreed, at the time he employed Clay Fulks, that Mrs. Babcock would edit all of Fulks’ copy. I had never had any news of this, and I have reason to believe that Henry [Alsberg—director of the Federal Writers’ Project] never knew it. Naturally, Mrs. Babcock, who knew it, and Floyd Sharp, who knew it, were up in the air over my memo. The reason Fulks’ copy was to be edited because of his known radical tendencies, and of his previous connection with Commonwealth.

“Well, I realized I had stuck my neck out, but I grinned with a certain joy in the fight, and the foreknowledge that something would come out of it to improve the situation, by these presents brought to light.

“Sharp suggested that I make use of a young man in his department, whose name now slips me, but whom I shall see tomorrow. At any rate, he is in a humor to do something, so the outlook is fairly encouraging.

“Fulks came up to my room after this letter was begun, and I outlined to him exactly what had happened. He was amenable to the situation as it now stands, and I admire his attitude. He met honesty with honesty and I feel there will be no trouble on his part whatever.”

Sept 30, 1936: “Mr. Sharp’s young man didn’t strike me very forcefully this morning. In fact he has a weak personality and is not the kind of writer we need. Bernie would ride him down in five minutes.

“Incidentally, I need to pay a tribute to Bernie. She was exceedingly nice to me this morning and I believe can stand the gaff better than I thought. I deliberately left the way to Washington open. She could have appealed to Henry or, more devastatingly, to Senator Joe. T. Robinson [Senate Majority Leader]. I haven’t whispered to Washington yet; I want to work this out first. And apparently Bernie has kept her peace. It would have surprised me to find a mean streak in her. Right now I don’t believe it’s there.”

Oct 4, 1936: “I can’t begin to tell you how much I appreciated your telling me Henry had confidence in me at Little Rock. To every practical intent I deposed Bernie as State Director and just then I needed to know I had support in Washington. I had plenty of it in Little Rock but it was no end of good to know at that moment that Henry was back of me.”