calsfoundation@cals.org

Benton County

| Region: | Northwest |

| County seat: | Bentonville |

| Established: | September 30, 1836 |

| Parent county: | Washington County |

| Population: | 284,333 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 847.72 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

2,228 |

3,710 |

9,306 |

13,831 |

20,328 |

27,716 |

31,611 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

33,389 |

36,253 |

35,253 |

36,148 |

38,076 |

36,272 |

50,476 |

78,115 |

97,499 |

153,406 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

221,339 |

284,333 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

201,188 |

70.8% |

| African American |

4,732 |

1.7% |

| American Indian |

5,093 |

1.8% |

| Asian |

13,721 |

4.8% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

2,629 |

0.9% |

| Some Other Race |

25,559 |

9.0% |

| Two or More Races |

31,411 |

11.0% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

50,540 |

17.8% |

| Population Density |

335.4 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$66,362 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$34,442 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

9.4% |

|

Located in the northwest corner of Arkansas, Benton County borders Missouri and Oklahoma and is part of the Ozark Plateau. The county has grown from a Native American hunting ground and a timberland and fruit resource to one of the fastest-growing and most economically vibrant counties in the country.

Pre-European Exploration

Evidence of Mississippian Culture in what is now Benton County can be seen through findings from the Goforth-Saindon Mound Group. Evidence suggests that the people living at the site were influenced by Caddo culture to the south. The Goforth-Saindon site is one of three known Mississippian Period mound centers in the Western Ozark Highland region.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the Osage Indians in Missouri made forays into the area for seasonal hunting. After the Louisiana Purchase, the U.S. government obtained major land cessions from the Osage, especially by an 1808 treaty. Cherokee agent Major William Lovely negotiated the cession of more Osage land in 1816 (renegotiated in an 1818 treaty), and all Osage land in the region had been ceded by 1825. The Arkansas Cherokee also ceded their land by 1828. This marked the last major Indian occupation of the area and opened it to legal white settlement.

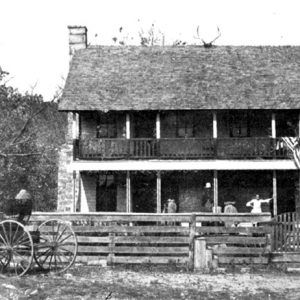

In 1827, part of the Lovely purchase became Lovely County, and, when Washington County was established a year later, it subsumed Lovely County and the land that today is Benton County. Adam Batie settled in 1828 near present-day Maysville on the county’s western border and is recorded as the first legal white resident. Maysville soon became the county’s first settlement.

Beginning in the late 1820s, white settlers increasingly moved into the area, drawn to the virgin timber supplies and the abundant supply of pure water in many rivers and creeks. Some came via army–built roads such as the State Road between Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and Springfield, Missouri, which was also a cattle-driving route with rest stops at Cross Hollows and Brightwater (both Benton County), where taverns served the drovers and stockyards penned cattle.

Benton County was formally established as a separate county from Washington County on September 30, 1836. It was named in honor of U.S. Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, who had played a key role in Arkansas’s admission into the Union. The county seat, Bentonville, was also named after Benton. Its post office opened in 1836, and the community soon thrived.

Many early county settlers came from Tennessee and other states of the upper South. Among them were the Blackburn and Van Winkle families, who settled around the area now known as War Eagle. Their sawmill, reportedly the largest in Arkansas, led James Austin Cameron (J. A. C.) Blackburn to become known as the Lumber King of northwest Arkansas. Other early settlers included the Reddick, Burks, and Sikes families and the German-born Sagers. African Americans arrived in the region as early as the 1830s, a few as freemen but most as slaves.

At least one enslaved person was lynched in the county before the Civil War. A man named Alph was lynched on August 20, 1849, by a group of white residents for killing his owner, James Anderson in Crawford County, while Anderson was transporting Alph south to be sold away from his wife, who remained in Benton County

In these early years, subsistence agriculture was the norm. Newcomers from Kentucky introduced tobacco cultivation, and it was a significant cash crop into the 1880s, after which low market prices led farmers to turn to more profitable crops, especially fruits such as apples, peaches, and strawberries.

In 1837, the Cherokee passed through the county on their forced Trail of Tears. Factionalism in the tribe saw Cherokee leader Stand Watie brought to trial in Bentonville in 1843 in a murder case. He was acquitted and went on to become a staunch Confederate supporter and the last Confederate general in the United States to surrender to Union forces.

A utopian commune existed in Benton County for four years before the Civil War. The Harmonial Vegetarian Society included at least thirty-eight members in 1860 but disappeared from the historical record the following year.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Benton County did not have a large enslaved population before the Civil War. A single free man of color lived in the county in 1860 along with 384 enslaved people. A total of 8,905 white citizens lived in the county the same year. The county was represented by two men at the Secession Convention, including A. W. Dinsome, who owned six enslaved people in 1860.

During the Civil War, many Benton County residents were caught between strongly Confederate Arkansans to the south and Union-supporting Missourians to the north. Cross Hollows was the site of a large 1861–1862 Confederate encampment, and the first military engagement in Arkansas, the Action at Pott’s Hill, was fought in Benton County, followed soon by an action at Dunagin’s Farm near present-day Avoca. In March 1862, the Battle of Pea Ridge, the most strategically decisive battle west of the Mississippi River, shifted the regional balance of power to the Union.

Most Confederate forces under the command of Major General Earl Van Dorn abandoned the state after the battle, crossing the Mississippi River to fight in Mississippi and Tennessee. This allowed the Union’s Army of the Southwest under Major General Samuel Curtis to move across northern Arkansas and threaten Little Rock (Pulaski County) before capturing Helena (Phillips County), both of which remained in Federal hands for the remainder of the war.

Bentonville and Fayetteville (Washington County) were the first two U.S. cities destroyed by fire in the war. Between the retreating Confederates, foraging Union troops, guerrilla forces loyal to each, and outlaws loyal to none, much of Benton County suffered destruction and severe food shortages. Numerous skirmishes and smaller engagements took place in the county during the war, with some settlements seeing multiple actions. Maysville was the site of at least three skirmishes, while Bentonville saw at least two.

Post Reconstruction through Early Twentieth Century

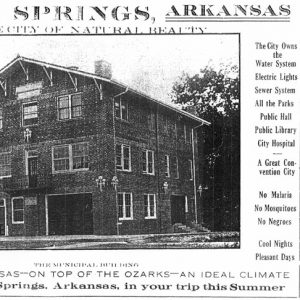

In the 1870s, the county’s population grew, but the number of black citizens decreased rapidly. Most left the area for better economic opportunities, some moving to Fayetteville. Those who stayed lived primarily in Bentonville, where in 1888 a school for black students was established. The number of farms almost doubled by 1880, with tobacco a major crop and subsistence farms often supplemented by fruit orchards.

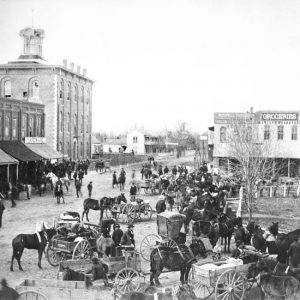

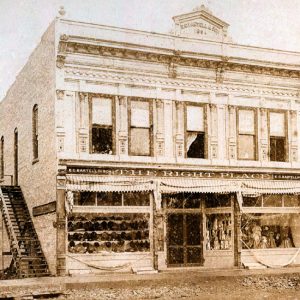

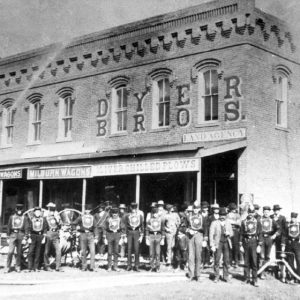

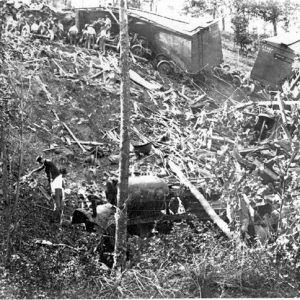

The railroad brought profound changes to the county in the early 1880s. The St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) built a line through the area, creating the towns of Rogers, Lowell, Garfield, Brightwater, and Avoca. The Kansas City, Fort Smith, & Southern Railway reached Sulphur Springs in 1889 and, reorganized as the Kansas City, Pittsburg, and Gulf Railroad, reached Siloam Springs in 1893. The KC, P and G sustained the town of Decatur and was reorganized in 1900 as the Kansas City Southern, which it remains today.

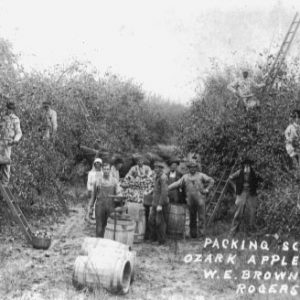

Railway transportation resulted in an influx of settlers. In 1888, Rogers opened its first free public school. Railroads brought tremendous growth in the fruit industry, which led to the creation of evaporators, canning factories, distilleries, and vinegar plants. The Arkansas and Oklahoma Western Railroad connected Rogers with Siloam Springs in 1907 and became known as the Fruit Belt Line due to the apple production in the county. In 1901, Benton County led the nation in apple production, producing 2.5 million bushels of apples and becoming known as the Land of the Big Red Apple. The Arkansas Black Apple was developed in Benton County, first being produced in 1870.

Benton County had some famous residents during this time. Two prominent political figures came from Bentonville: Colonel Samuel Peel was elected to Congress in 1883 and served five terms, and James Berry was a state representative, governor, and U.S. senator. William “Coin” Harvey, famed financial writer and free-silver advocate, created the Monte Ne resort in 1900 and ran for president in 1931. In the 1920s, he planned to construct a pyramid as a time capsule but died before it was built. Architect A. O. Clarke came from St. Louis and designed some of the most impressive buildings in the county in the early 1900s including the Benton County Courthouse. Betty Blake married entertainer Will Rogers in 1908 in her family’s Rogers home.

More than 1,000 Benton County soldiers boarded troop trains beginning in June 1917 on their way to service in World War I, while civilians on the home front kept busy with Red Cross work and war bond drives. Captain Field L. Kindley of Gravette was the second-ranking World War I flying ace; he died in an aircraft accident at Kelley Field in San Antonio, Texas, in 1920.

Benton County had a bumper crop of five million bushels of apples in 1919. But by 1920, diseases such as San Jose scale and cedar rust devastated apple crops, and late frosts and hot, dry summers also took their toll. Around 1921, Edith Glover of Cave Springs had financial success growing a flock of broiler chickens, thus influencing her father to become the first large-scale broiler producer in the county. By 1924, Benton County led the state in egg production.

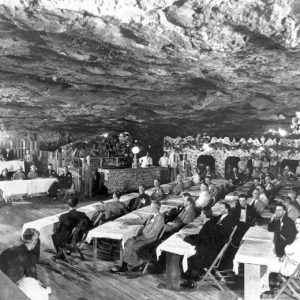

The Linebarger brothers developed the Bella Vista resort in 1917, and its popular Wonderland Cave nightclub hosted an unofficial session of the legislature in 1931. In 1919, Methodist evangelist John E. Brown Sr. founded Southwestern Collegiate Institute (now John Brown University) in Siloam Springs. His 1928 radio station was the first in Benton County.

During the Depression, the U.S. government’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) supported many county projects, including the construction of Rogers’s Lake Atalanta in 1937. Senator Clyde Ellis of Garfield secured legislation to create the first rural electric cooperatives in the state, prompting the 1937 organization of the Carroll Electric Cooperative in the county.

The 1930s and 1940s saw the expansion of the poultry industry. By 1938, Benton County was the largest broiler-producing county in the nation, fueled by Tyson Foods and Peterson Hatchery. Meanwhile, Bentonville aviator Louise Thaden was soaring into the record books, including first place in the 1936 Bendix Transcontinental Air Race. The Arkansas-Missouri League, operating from 1934 to 1940, included minor league baseball teams in Bentonville, Rogers, and Siloam Springs.

World War II through the Faubus Era

More than 1,800 Benton County residents served in the armed forces during World War II. Battery F of the 142nd Field Artillery was mobilized in 1940, and the Rogers Home Guard formed two years later. By war’s end, 120 Benton County soldiers had died.

After the war, business started to boom. Rogers Municipal Airport opened in 1945 and assisted the poultry-hatching industry; between 1947 and 1951, Operation Chicken Haul flew in loads of baby chicks. Sam Walton opened a five-and-dime store in Bentonville in 1950 and his first Walmart Inc. store in Rogers in 1962. Daisy Manufacturing moved its entire air gun production operation to Rogers from Michigan in 1958.

Population and tourism began to soar in the 1960s. The 31,700-acre Beaver Lake, completed in 1966 at a cost of more than $46 million, provided flood control, electricity, and a regional water supply. Retirees were attracted by the development of Bella Vista Village, which has become one of the largest planned communities in the country. Along with smaller fairs, the War Eagle Fair, a craft show and sale begun in 1954, has made the county a mecca for some 200,000 visitors each fall. The 4,300-acre Pea Ridge National Military Park was dedicated in 1963, and the 12,054-acre Hobbs State Park-Conservation Area, bought by the state in 1979, is Arkansas’s largest and the county’s only state park. The Ozark-St. Francis National Forest extends into the southwestern corner of the county. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art opened in Bentonville in 2011, showcasing both artwork and architecture.

Modern Era

The last few decades of the twentieth century brought rapid growth and a booming economy to Benton County. Between 1990 and 2000, the county’s population grew fifty-seven percent, largely driven by a 900-percent increase in Latino immigration to the area. The 2010 census showed a continuation of the growth trend. Also boosting the county’s economy is Walmart Inc., headquartered in Bentonville. As the world’s top retailer, it is not only the county’s but the world’s largest employer. Supporting their Walmart Inc. accounts, many large and small businesses have moved in, bringing thousands of new residents from across the country. Other top employers in the county include J. B. Hunt Transport, Arvest Bank Group, McKee Foods, Peterson Farms, Simmons Foods, Franklin Electric Company, Gates Rubber Company, and La-Z-Boy.

Rogers is the largest city in the county and the ninth largest in Arkansas. Since 1990, industry has invested more than $900 million in the city and created more than 9,000 jobs. Major employers include Tyson Foods, St. Mary’s Hospital, Glad Products Company, Rogers Tool Works, and Superior Industries.

Agribusiness, chiefly poultry and cattle, also remains important. In 2002, Benton County led the state in production of hay and pasture for livestock.

Rapid population growth has necessitated infrastructure improvements. Northwest Arkansas National Airport (XNA) opened in 1998, what is now Interstate 49 through Benton County was completed by 1999, and the Two-ton Loop pipeline began carrying water from Beaver Lake to Benton and Washington counties. Northwest Arkansas Community College in Bentonville, one of the fastest-growing two-year colleges in Arkansas, opened in 1990.

In the 1990s, the county’s rate of growth for personal income was more than nine percent, significantly higher than that of the state and the country. In 2002, it had the largest percentage of new residents in Arkansas, most attracted by employment opportunities. By 2010, Benton County was the state’s second-most-populous county, and it remained so in 2020. The county still maintains its blend of Midwestern, Western, and Southern small-town sensibilities, but it is increasingly becoming part of a more global community. The Ozark-St. Francis National Forest extends into the southwestern corner of the county. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art opened in Bentonville in 2011, showcasing both artwork and architecture.

Bentonville native Asa Hutchinson was elected the forty-sixth governor of Arkansas in 2014 and reelected in 2018. Hutchinson previously served in the U.S. House of Representatives and began his political career as the city attorney for Bentonville. His older brother, Tim Hutchinson, represented the state in both the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate.

For additional information:

Benton County Heritage Committee. History of Benton County, Arkansas. Rogers: Benton County Heritage Committee, 1991.

Benton County Pioneer. Siloam Springs, AR: Benton County Historical Society (1955–).

Black, J. Dickson. History of Benton County. Little Rock: International Graphics Institute, 1975.

Easley, Barbara P., and Verla P. McAnelly, eds. Obituaries of Benton County, Arkansas. 11 vols. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1994–1998.

Goodspeed’s 1889 History of Benton County, Arkansas. Bentonville, AR: Benton County Historical Society, 1993.

Jines, Billie. Benton County Schools That Were. 5 vols. Ozark, MO: Dogwood Publishing, 1989–1996.

Phillips, George H. Handling the Mail in Benton County, Arkansas, 1836–1976. Siloam Springs: Benton County Historical Society, 1979.

Allyn Lord

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.