calsfoundation@cals.org

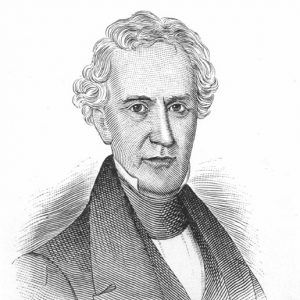

Benjamin Johnson (1784–1849)

Benjamin Johnson was a judge of the Superior Court of the Arkansas Territory (predecessor to the Supreme Court of Arkansas) and later the first federal district judge for the state of Arkansas. He was a part of the early Arkansas political dynasty known as “The Family.” Johnson County in northwestern Arkansas is named for him.

Benjamin Johnson was born on January 22, 1784, in Scott County, Kentucky, to Robert and Jemima Johnson. The Johnsons were leaders in political, educational, and religious affairs in early Kentucky and one of the most prominent families in the state.

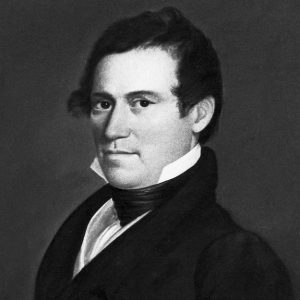

Five of Johnson’s eight brothers served in the War of 1812, and one, Richard Mentor Johnson, gained fame as the man who killed the great Shawnee leader Tecumseh at the Battle of the Thames in 1813. Richard Johnson later served as a U.S. congressman and senator, and in 1836, he was elected vice president of the United States on a ticket with Martin Van Buren. Johnson’s younger brother Joel moved to the Arkansas Delta in the early 1830s and established Lakeport Plantation, which became one of the largest and most successful cotton plantations in the state.

Johnson married Matilda Williams in September 1811, and they eventually had eight children. The couple moved to Lexington, Kentucky, where Johnson chose to pursue a legal career and gained admittance to the bar in the Lexington Circuit, where, as one early historian noted, “his ability and popularity soon marked him for the high station of jurist.” He later served as a circuit judge and a district judge in the Lexington area.

In 1821, President James Monroe appointed Johnson to be one of three judges of the Superior Court for the Arkansas Territory. He was reappointed by presidents John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson and served in that capacity until 1836. His tenure on the territorial bench was the longest in Arkansas history. Because Superior Court sessions were held in Little Rock (Pulaski County), Johnson took up residence there. When Arkansas became a state in 1836, President Jackson appointed Johnson to be the state’s first federal district judge.

He was apparently a man of some means when he arrived in the territory, and his tenure on the territorial bench seemed to do nothing to diminish his standing. In 1830, he was reputed to be the second largest slave owner in Pulaski County, with twenty-one slaves. In 1832, he purchased a large home, which became a Little Rock landmark. It was located on the site of the current Albert Pike Hotel.

In addition to his judicial duties, Johnson was active in Arkansas politics. His family had long been associated with the Democratic-Republican Party in Kentucky (the party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in opposition to the Federalist Party of Alexander Hamilton), and Johnson was a staunch supporter of Andrew Jackson. In Arkansas, Johnson allied himself with the Conway and the Sevier families to form a Democratic political dynasty known as “The Family.” This political union was solidified in 1827, when Johnson’s oldest daughter Juliette married Ambrose H. Sevier, an aspiring Arkansas politician who was also related to the Conways. The Johnson-Conway-Sevier dynasty dominated Arkansas politics until the Civil War.

Politics in early nineteenth-century Arkansas was a rough-and-tumble affair, and Judge Johnson’s tenure was not without controversy. In 1827, his decisions in favor of the holders of some fraudulent Spanish land grant claims, including a number of prominent members of the Arkansas bar, were strongly criticized and tarnished the image of the territorial court. The decisions were later overturned by a higher court. In 1832, some of the Family’s political opponents brought impeachment charges against Johnson. Territorial governor John Pope and a host of other state officials and members of the bar rushed to Johnson’s defense, and the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives exonerated him of any wrongdoing. These controversies notwithstanding, Johnson’s career was a distinguished one because of his long tenure as a territorial and federal judge, because of his being a founding member of the state’s most powerful political dynasty, and because of the esteem in which he was held by friends and many foes. In November 1833, Johnson County was formed and named after him.

In July 1849, Johnson’s granddaughter, Ann Sevier, married Thomas Churchill, a Mexican War veteran and a native Kentuckian who later became Arkansas’s thirteenth governor. Three months after the wedding, on October 2, 1849, Johnson died at the family home in Lexington, Kentucky.

At the time of his death, Johnson could claim to have been Arkansas’s greatest jurist. Albert Pike, of the opposing Whig Party, remarked, “There never lived a more honest, upright, honorable or generous man than Benjamin Johnson,” and his court reporter wrote, “He died full of judicial honors, beloved by all; admired for the purity of his public life and private character, and for his devotion as a citizen; respected for unbending integrity and for a heart full of kindness to all.” is buried in Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Bevins, Ann Bolton. The Ward and Johnson Families of Central Kentucky and the Lower Mississippi Valley. Georgetown, KY: The Ward Hall Press, 1984.

DeBlack, Thomas A. “A Garden in the Wilderness: The Johnsons and the Making of Lakeport Plantation, 1831–1876.” Ph.D. diss., University of Arkansas, 1995.

Foster, Lynn. “Their Pride and Ornament: Judge Benjamin Johnson and the Federal Courts in Early Arkansas.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 22 (Fall 1999): 21–48.

Hallum, John. Biographical and Pictorial History of Arkansas. Vol. 1. Albany: Weed, Parsons, and Company, 1987.

Reynolds, John Hugh. Makers of Arkansas History. Little Rock: R&R Pub. Co, 1918.

Thomas A. DeBlack

Arkansas Tech University

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.