calsfoundation@cals.org

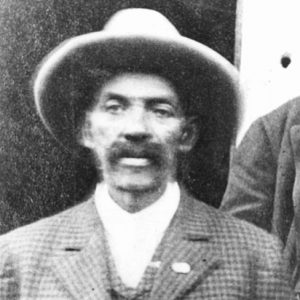

Bass Reeves (1838–1910)

Arkansas native Bass Reeves was one of the first Black lawmen west of the Mississippi River. As one of the most respected lawmen working in Indian Territory, he achieved legendary status for the number of criminals he captured.

Bass Reeves was born enslaved in Crawford County in July 1838. His owners, the William S. Reeves family, moved to Grayson County, Texas, in 1846. During the Civil War, Bass became a fugitive slave and found refuge in Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma) amongst the Creek and Seminole Indians. Reeves is believed to have served with the irregular or regular Union Indians that fought in Indian Territory during the Civil War.

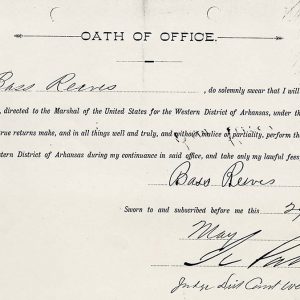

After the Civil War, Reeves settled in Van Buren (Crawford County) with his wife, Jennie, and children. Oral history states that Reeves served as a scout and guide for deputy U.S. marshals going into Indian Territory on business for the Van Buren federal court. In 1875, Judge Isaac C. Parker became the federal judge for the Western District of Arkansas, which had jurisdiction over Indian Territory. This court had moved to Fort Smith (Sebastian County). In 1875, Reeves was hired as a commissioned deputy U.S. marshal, making him one of the first Black federal lawmen west of the Mississippi River.

During his law enforcement career, Reeves stood 6’2″ and weighed 180 pounds. He could shoot a pistol or rifle accurately with his right or left hand; settlers said Reeves could whip any two men with his bare hands. Reeves became a legend during his lifetime for his ability to catch criminals under trying circumstances. He brought fugitives by the dozen into the Fort Smith federal jail. Reeves said the largest number of outlaws he ever caught at one time was nineteen horse thieves he captured near Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The noted female outlaw Belle Starr turned herself in at Fort Smith when she found out Reeves had the warrant for her arrest.

In 1887, Reeves was tried for murder for the shooting of his trail cook, but he was found innocent. In 1890, Reeves arrested the notorious Seminole outlaw Greenleaf, who had been on the run for eighteen years without capture and had murdered seven people. The same year, Reeves went after the famous Cherokee outlaw Ned Christie. Reeves and his posse burned Christie’s cabin, but he eluded capture.

In 1893, Reeves was transferred to the East Texas federal court at Paris, Texas. He was stationed at Calvin in the Choctaw Nation and took his prisoners to the federal commissioner at Pauls Valley in the Chickasaw Nation. While working for the Paris court, Reeves broke up the Tom Story gang of horse thieves that operated in the Red River valley.

In 1897, Reeves was transferred to the Muskogee federal court in Indian Territory. Reeves remarried in 1900 to Winnie Sumter; his first wife had died in Fort Smith in 1896. In 1902, Reeves arrested his own son, Bennie, for domestic murder in Muskogee. Bennie was convicted and sent to the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Reeves worked until Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907, at which time he became a city policeman for Muskogee. He died of Bright’s disease on January 12, 1910.

On May 26, 2012, a bronze statue depicting Reeves on a horse riding west was dedicated in Fort Smith’s Pendergraft Park. The statue, which was designed by sculptor Harold T. Holden and cost more than $300,000, was paid for by donations to the Bass Reeves Legacy Initiative. On July 24, 2024, the Arkansas Secretary of State‘s office and the U.S. Marshals Museum announced that they were seeking artists for a possible formal portrait of Reeves to hang in the Arkansas State Capitol. On December 18, 2024, the portrait, by James Loveless Jr. of Texas, was unveiled, making Reeves the first African American to have an official portrait on display at the capitol.

In the twenty-first century, Bass Reeves has emerged as a pop culture figure across the world. For example, he appeared in the acclaimed 2019 HBO series Watchmen, was the subject of a comic book series published by Allegiance Arts starting in 2020, and appeared in 2020 in an issue of the Franco-Belgian comic book series Lucky Luke titled, “Un Cow-Boy Dans Le Coton” (published in English the following year as “A Cowboy in High Cotton”). He was also the subject of Sidney Thompson’s trilogy of historical novels: Follow the Angels, Follow the Doves (2020), Hell on the Border (2021), and The Forsaken and the Dead (2023). The July 2021 cover story for Texas Monthly magazine focused upon the broader legacy of Reeves. Reeves was also a character in the western films Hell on the Border (2019) and The Harder They Fall (2021), as well as the Paramount+ western series Lawmen: Bass Reeves, which starred David Oyelowo as Reeves and premiered on November 5, 2023.

For additional information:

Bowden, Bill. “Black Lawman a Star in France.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 28, 2021, pp. 1A, 7A.

Burton, Art. Black Gun, Silver Star: The Life and Legend of Frontier Marshal Bass Reeves. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

———. Black, Red and Deadly: Black and Indian Gunfighters of the Indian Territory, 1875–1907. Austin, TX: Eakin Press, 1991.

Ellis, Dale. “TV Series Sparking Interest in Marshal.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 26, 2023, pp. 1A, 2A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/dec/26/tv-series-sparking-interest-in-legendary-us/ (accessed December 27, 2023).

“He’s a Bad Indian.” Arkansas Gazette, April 29, 1890, p. 7.

Snyder, Josh. “Reeves Portrait Unveiled at Capitol.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 18, 2024, pp. 1B, 5B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/dec/18/state-capitol-unveils-portrait-of-reeves-famed/ (accessed December 19, 2024).

Wallace, Christian. “The Resurrection of Bass Reeves.” Texas Monthly, July 2021. https://www.texasmonthly.com/being-texan/the-resurrection-of-bass-reeves/ (accessed February 11, 2026).

Williams, Nudie E. “Bass Reeves: Lawman in the Western Ozarks.” Negro History Bulletin 42, no. 2 (1979): 37–39.

Art T. Burton

Harvey, Illinois

I am really upset because this will never be taught in schools due to not wanting to teach “Black history.” All history needs to be taught. When I was thirteen, I started to follow Martin Luther King’s movement, which started me to dig into Black history because I knew it had to be more than just white history. I am now seventy-four, and I teach everyone about our history.

I think it’s great that our next generation will get to know the greatness of Bass Reeves. I was stunned to just learn about Bass. I’m a senior citizen now, but I feel like a youth inside, now that I’ve found a new Black Hero.

My maternal great-grandfather was Richard Joseph (Dick) McStravick. He was an Irish immigrant who came to Fort Smith, Arkansas, to be a guard for Judge Isaac Parker in approximately 1892. He served Judge Parkers court until Oklahoma statehood in 1907. (This is verified by the museum records.) He then moved to Muskogee, Oklahoma, where he hired on as a jailer for the Muskogee County Jail. The census in 1920 showed him to be a night watchman for an oil company, which indicates he retired from the jail. He died in 1924. With him being in Fort Smith and in Muskogee at approximately the same time frame as Bass Reeves, it is sure that the two were acquainted. My first cousin in Jefferson City, Missouri, is in possession of the .45 caliber pistol that my great-grandfather carried during his career in law enforcement.