calsfoundation@cals.org

Act 112 of 1909

aka: Anti-Nightriding Law

aka: Anti-Whitecapping Law

Act 112 of 1909 was a law designed to curb the practice of nightriding or whitecapping, terms that encompass a range of vigilante practices typically carried out for 1) the intimidation of agricultural or industrial workers, typically by poor whites against African Americans, with the hope of driving them from their place of employment and thus positioning themselves to take over those jobs, or 2) the intimidation of farmers or landowners with the aim of preventing them from selling their crops at a time when the price for such was particularly low, done with the hope of raising the price for these goods. As such acts of vigilantism began to threaten the profits of landowners and industrialists, nightriding was prosecuted by state and local authorities—at least more so than other forms of violent vigilantism, such as lynching. The terms “nightriding” and “whitecapping” come from practices of carrying out attacks at night and/or while disguised, perhaps in white hoods that hearken back to the Ku Klux Klan of Reconstruction.

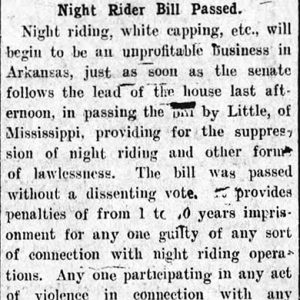

Representative A. G. Little of Mississippi County began his term of service in the Arkansas House of Representatives by introducing, in January 1909, what the Fort Smith Times called “a red-hot bill against night riding.” The Arkansas Democrat featured the newly minted state representative, complete with picture, in its “Among the Law Makers” section on January 21, 1909, due to his measure to suppress nightriding and whitecapping, noting that “his bill proposes such stringent punishment as will prevent the occurrence of such acts of violence as have visited Kentucky and Tennessee.” At the time, violence in the “Black Patch” region of Kentucky and Tennessee, where much of the nation’s tobacco was grown, had reached a fever pitch as vigilantes sought to shore up opposition to monopolistic buyers by intimidating fellow farmers. Nightriding violence had persisted for several years, taking the form of attacks upon people and on property such as barns, fields, and livestock.

Arkansas had already witnessed nightriding violence during several years prior to 1909. In January 1894, unknown individuals posted notices in and around Black Rock (Lawrence County) warning African Americans to leave town within ten days. In October 1887, a “party of masked men” attacked black tenant houses in Clover Bend (Lawrence County) and ordered the residents to leave the county. In early 1884, violence erupted in Prairie Township of St. Francis County, with several homes being burned in response to white farmers having had their mortgages foreclosed by merchants to whom they were in debt. However, authorities were not powerless to prosecute nightriding before 1909, as there were many other crimes with which perpetrators could be charged. In fact, two prosecutions of nightriders in Arkansas resulted in cases that reached the U.S. Supreme Court: United States v. Waddell et al. (1884) and Hodges v. United States (1906).

Upon its introduction, House Bill 80, as it was known, made its way through the Arkansas General Assembly with remarkable ease, encountering no obstacles in committee and being supported unanimously in both the House and Senate. Governor George Donaghey signed the bill into law on April 6, 1909. The act defined various forms of nightriding—including going out in disguise at night to intimidate or assault people or to damage or destroy property, as well as the delivery or posting of threatening notices—and set various prison terms and fines.

An editorial in the Arkansas Gazette praised Act 112 as “an effective deterrent to any future manifestations of the night rider spirit in Arkansas.” Some newspapers endorsed the measure by reprinting the bill in whole or in part. However, only a few weeks following the law’s passage, the deputy prosecuting attorney of Lonoke County was considering the prosecution of three young white men for having violated the act with “having taken a negro into the woods near Cabot at night with the intention of whipping him, with firing 13 shots at him, when he escaped from them, and with later creating a disturbance at several other negro homes.” They were charged with nightriding but ultimately not convicted on this charge. According to contemporary newspaper records, the first white man convicted of a crime under Act 112 was J. R. Bush of Jefferson County, who fired shots into a group of African-American timber workers.

As historian Jeannie M. Whayne has written, although authorities regularly arrested and prosecuted nightriders, “the 1909 state law clearly had been ineffective in halting nightriding activities, and although passed at the behest of planters who felt powerless to conserve their labor force, the law was used as often to quell vigilante violence perpetrated by whites against other whites. In at least one case it was used to suppress striking workers.” Instances of nightriding continued on into the 1920s, especially in the cotton-growing region of northeastern Arkansas. In one April 1921 court case in Jonesboro (Craighead County), some twenty white farmers who had engaged in nightriding—having threatened their fellow farmers against selling cotton during a slump in price—pleaded guilty to the charge. However, Act 112 was often employed against African Americans and others who were organizing for collective benefit. Several members of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America were arrested and charged with nightriding in the wake of the Elaine Massacre of 1919. Likewise, eleven African Americans who had gathered in a log cabin for self-defense were charged with, and convicted of, nightriding following the Catcher Race Riot of 1923; the baselessness of this charge was too much for the Arkansas Supreme Court, which overturned their conviction the following year. In the 1930s and 1940s, members of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU) were charged with nightriding after such acts as posting strike notices during the night.

By the twenty-first century, hate crimes legislation and laws against “terroristic threatening” had largely subsumed anti-nightriding laws.

For additional information:

“Accused Farmers Say Plead Guilty.” Arkansas Gazette, April 27, 1921, p. 1.

“Among the Law Makers.” Arkansas Democrat, January 21, 1909, p. 6.

“Bush Taken to the State Prison.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, October 14, 1910, p. 6.

Lancaster, Guy. “‘Night Riding Must Not Be Tolerated in Arkansas’: One State’s Uneven War against Economic Vigilantism.” In Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta: Essays to Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre, edited by Michael Pierce and Calvin White. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

———. “Nightriding and Racial Cleansing in the Arkansas River Valley.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Autumn 2013): 242–264.

Lancaster, Guy, ed. “Nightriding in Arkansas.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Autumn 2022).

“May Prosecute under New Act.” Arkansas Gazette, May 16, 1909, p. 1.

“Night Riding Bill a Law.” Arkansas Democrat, April 7, 1909, p. 6.

“Stop Night Riders.” Fort Smith Times, January 17, 1909, p. 1.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth-Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law Night Rider Bill

Night Rider Bill

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.