calsfoundation@cals.org

Tropes Common to Lynching Reports

While the details of Arkansas’s many lynchings (mostly of African Americans) differ widely, some common themes or tropes were used in the newspaper reports related to them. The most common of these were: 1) language employed to dehumanize the victims of lynching; 2) descriptions of the mob as quiet and orderly; 3) statements to the effect that the local African-American community approved of these acts of vigilantism; 4) reports of victims confessing to their crimes prior to being lynched; and 5) statements that perhaps exaggerate the efforts of law enforcement to prevent such violence.

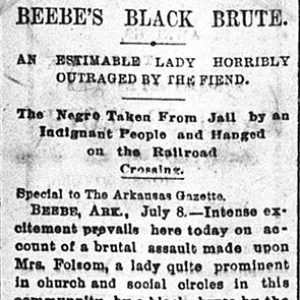

The propensity to demonize or dehumanize lynching victims was especially prominent if these people were accused of attacking a white woman or girl. In 1892, the Memphis Commercial Appeal, commenting on Northern newspapers’ description of lynching as “Southern barbarism,” declared that “the ‘Southern barbarism’ which deserves the serious attention of all people North and South, is the barbarism which preys upon meek and defenseless women. Nothing but the most prompt, speedy and extreme punishment can hold in check the horrible and bestial properties of the Negro race.” A number of African Americans in Arkansas, accused of attacking young white girls, were described in dehumanizing language. Sometimes, these comments centered on the appearance of the alleged perpetrator. The Arkansas Gazette described Joseph Young, accused of raping a woman in 1883, as “coal black,” “low-browed,” and “possessed of a heavy chin, wide nose and thick lips…Altogether he is a horrible-looking object, resembling a beast more than a human being.” Quite often, newspapers employed religious language to convey the ostensibly evil nature of those men who were lynched. Henry Smith, lynched in 1881, was referred to as a “monster,” and Levi Graves, age sixteen and lynched in 1888, was called a “young fiend.” Albert Williams, lynched in Union County in 1883, was described as “a brutal negro” and an “outraging demon.” John Hogan, accused of trying to attack a young girl in 1875, was described in the Arkansas Gazette as “an abandoned wretch” possessed of “brutish propensities,” and Leach Magee, accused of attacking a white woman in 1887, was referred to as a “hell-born wretch.”

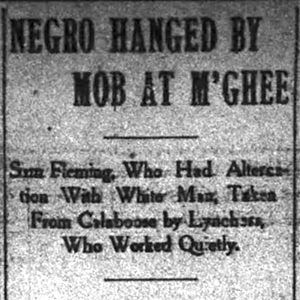

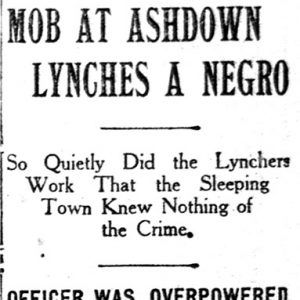

Newspapers often referred to lynch mobs as quiet and organized, even when the crowd was so large as to make that seem dubious. According to the New York Times, the mob that shot three men in Arkansas County in 1891 operated quietly, and “no one knew the leaders.” Things were reportedly quiet in town after the lynching, and “business is going on as if nothing unusual has happened.” The Deseret Evening News of Salt Lake City, having received a telegram about the lynching, noted: “Remarkable to state, the telegram describes the tragedy as a quiet and orderly affair. It ought to have added that it was high toned and respectable.” According to the Arkansas Gazette, the lynching of Leach Magee in 1887 by forty men in the middle of downtown Clarendon (Monroe County) happened quietly, with no “fuss or hurrah.” A mob numbering 100 people in Augusta (Woodruff County) reportedly managed to hang Arthur Dean, accused of attacking a white woman, in “as quiet and orderly a manner as would have been possible at a legal execution.” Likewise, when Charles Richardson and Robert Austin were hanged by a mob numbering 300 in 1910, the Arkansas Gazette noted that the lynching was “conducted in a businesslike fashion.”

Another recurring theme is that both whites and African Americans are alleged to have approved of these lynchings. For example, when Levi Graves was lynched in Sevier County in 1888, the Arkansas Gazette reported that “the negroes all say: ‘Well done’…and as there is no doubt about the assault, all of the community appreciate the mob’s work.” The same was allegedly true in the lynching of Albert Williams in 1883, when the Fayetteville Weekly Democrat reported that “whites and blacks both seem to endorse the proceeding with almost unanimous voice.” After Leach Magee was lynched in 1887, black residents of Clarendon reportedly refused to bury him, saying he was a “disgrace upon their people.”

According to reports, many lynching victims supposedly confessed to their crimes. Some supposed jailhouse confessions were undoubtedly spurious. Historian Story L. Matkin-Rawn noted the case of two young African Americans who were accused of killing a white boy in 1928. Subsequent investigation by their lawyer revealed that they had been beaten for hours and threatened with the electric chair. Some alleged perpetrators confessed when faced with lynching. When a large mob lynched Henry James in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1892 for attacking a young white girl, he at first refused to confess. Just before he was hanged, when pressed again, he said, “I guess I am guilty.” First reports on the alleged 1882 attack on a young white girl named Annie Bridges in Butlerville (Lonoke County) indicated that she had invented the account to explain arriving home late. When authorities later deemed her allegations credible, Joseph Earl, Taylor Washington, and Thomas Humphreys were arrested. They told a justice of the peace that they had alibis, but before those alibis could be provided, a mob took them from the jail and hanged them. The youngest, in an apparent attempt to escape lynching, confessed to the crime at the last minute, but the others maintained their innocence.

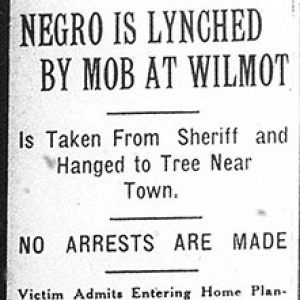

A final theme in lynching reports was that law enforcement officials had posted “a strong guard” to protect the prisoners in their custody, when in fact their precautions were minimal. Before Hamp Biscoe and his family were slaughtered in Lonoke County in 1892, they were secured only in a small frame house with two young guards to protect them. After being bound over for the grand jury in 1892, Julius Mosely was put under the care of a single constable, who was keeping him in his home. A large mob subsequently took him from the constable and hanged him. That same year, law enforcement officials seemed to intentionally leave a prisoner to the mercy of the mob. When a mob gathered outside the penitentiary in Little Rock demanding prisoner Henry James, penitentiary manager Colonel S. M. Apperson sent the guards to their quarters and chose to meet the mob on his own. In 1921, Henry Lowery, being brought back to Arkansas from Mississippi to face trial, was handed over to a mob in Mississippi with “lamb-like docility” and taken into Arkansas by a roundabout route rather than directly to the state penitentiary. Governor Thomas C. McRae accused the officers of negligence, declaring that Lowery had been burned at the stake without any attempt to prevent his lynching. When Winston Pounds was arrested in 1927, Sheriff John C. Riley left him unattended in his car while he talked with his deputies and several businessmen. A group of men jumped into the car and drove out of town in a caravan of cars, and Pounds was hanged.

An analysis of these various tropes illustrates that they were used to legitimize or justify these extra-legal and often extremely brutal punishments. These were not by any means the only such tropes to be employed in the service of justifying mob violence, but they were the most common. Reflection upon the repetition of these particular tropes should make the reader of historical newspaper accounts of lynching somewhat wary as to the veracity of events as they were so described.

For additional information:

Buckelew, Richard. “Racial Violence in Arkansas: Lynchings and Mob Rule, 1860–1930.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1999.

Lancaster, Guy, ed. Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

Matkin-Rawn, Story L. “‘We Fight for the Rights of Our Race’: Black Arkansans in the Era of Jim Crow.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin–Madison, 2009.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. On Lynchings. Edited by Patricia Hill Collins. Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2002.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Davidson, North Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Mass Media

Mass Media Bailey Lynching Article

Bailey Lynching Article  Fleming Lynching Article

Fleming Lynching Article  McClain Lynching Article

McClain Lynching Article  Pounds Lynching Article

Pounds Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.