calsfoundation@cals.org

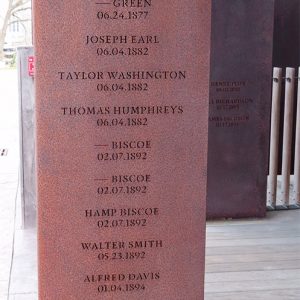

Lynching of the Biscoe Family

In early February 1892, Hamp Biscoe (or Bisco), his pregnant wife, and his thirteen-year-old son were killed in Keo (Lonoke County); their infant escaped with only a minor wound. This murder was apparently the culmination of years of suffering and bitterness on the part of the Biscoe family. It was also one of the numerous incidents occurring in Arkansas at the time that prompted the Reverend Malcolm E. Argyle to write in the March 1892 Christian Recorder (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania): “There is much uneasiness and unrest all over this State among our people, owing to the fact that the people (our race variety) all over the State are being lynched upon the slightest provocation….In the last 30 days there have been not less than eight colored persons lynched in this State….It is evident that the white people of the South have no further use for the Negro.”

According to reports made by R. H. CarlLee and published in the Arkansas Democrat, Hamp Biscoe had a small farm near England (Lonoke County), which he had pre-empted and subsequently farmed very successfully for about ten years. (The Preemption Act of 1841 allowed “squatters” who were living on federal land to purchase up to 160 acres at low prices before the land was to be offered for sale to the general public; among other requirements, a purchaser had to be a citizen over twenty years of age, the head of a household, and a resident on the land for at least fourteen months.) Six or seven years after Biscoe had acquired the land, the man who had first shown him the land appeared and proceeded to ask him for $100 in payment for doing so. Biscoe refused to pay, the man filed and won a judgment, and the land was sold to pay off the debt. In consequence, according to CarlLee, “The negro had become crazy of the injustice done him to such an extent that he would permit but few men, white or black, to come on the place, suspecting all of wanting to steal his place from him.”

Sometime during the first week of February 1892, Biscoe’s neighbor, identified only as Mr. Venable, let down the fence between their properties and attempted to pass through Biscoe’s field. Biscoe drove him away with violent threats. Venable filed a complaint, and a warrant was issued. Deputy Constable Jonathan Ford attempted to serve this warrant on Saturday, February 6. However, Biscoe refused to come out of the house, and his wife and son ordered Ford off the property.

Ford returned with a black deputy and two white men the following day. Biscoe declared that he “would not be arrested alive, and would kill them all if they attempted it.” The deputy drew his gun to cover Biscoe, but Ford ordered him not to shoot. The deputy remonstrated, saying that if Biscoe managed to get into the house, Biscoe would shoot all the men. Biscoe did go into the house, got his gun, and ordered them off the property. Ford tried to reason with him, saying that it was senseless to resist arrest for such a minor offense. He then opened the gate into the yard, whereupon either Biscoe or his teenage son, “at the command of his mother,” shot Ford in the side. Ford managed to draw his gun and shoot, inflicting a scalp wound on Biscoe and wounding his wife in the arm. The deputy then shot Biscoe in the small of the back as he was running back into the house. The posse then left, leaving Ford for dead, and Biscoe barricaded himself in the house.

James Beauchamp and another white man happened to be nearby and went to the scene. They forced open the door of Biscoe’s home and apprehended Biscoe, who was unable to stand, as well as his wife and son. Ford, as it turns out, was alive but was also unable to stand. He was carried to his home, where he was recovering. The Biscoe family was taken to a small frame house across from the depot in Keo, where they were put under the guard of two young African-American men. While there were rumors that the family would be lynched, most thought it was improbable, as Ford was not severely wounded, and Biscoe was both severely wounded and known to be mentally deranged. Later that night, a dozen or so men came to the house and told the guards that they should leave, which they did, going to a nearby black church, where they tried to persuade the preacher to stop the mob. The shooting, however, began in minutes, with as many as forty shots being fired. The murderers left immediately afterward, and the African Americans from the church went to the house, where they found Biscoe and his wife dead, and the baby with a slight wound near its upper lip. The Biscoes’ son, while seriously wounded, lived for several hours and was able to talk coherently about the shootings.

According to the boy’s account, his father was shot first. When the boy tried to escape from the house, a young man shot him in the abdomen. Another man shot the boy’s mother, while a “taller young man whom he did not know” shot his father yet again. After killing the boy’s two parents, one of the murderers removed $220 that the boy’s mother had hidden in her stocking. Apparently, she had been seen with the money earlier in the day and had accused the killers of attacking the family to get the money. On their way out the door, one of the murderers turned the boy over and shot him again, this time in the chest. They left, and the remainder of the crowd waiting out in the yard fired a number of shots into the air and then also departed.

Apparently, authorities must have had some idea who committed the crimes, because CarlLee asked the Democrat to suppress the names of the men “charged by the negroes with the killing.” In the following days, national press coverage was extensive. Most of the stories indicate that only two men, masked, were involved in the shootings. They also add the interesting detail, perhaps fanciful, that the killers had been dressed in women’s clothing.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett covered the Biscoe murders in a chapter in her book The Red Record titled “Lynching Imbeciles (An Arkansas Butchery).” The story she tells is based almost entirely on the Democrat’s February 11, 1892, article. Wells-Barnett herself adds the following editorial comment: “Perhaps the civilized world will think, that with all these facts laid before the public, by a writer who signs his name to his communication, in a land where grand juries are sworn to investigate, where judges and juries are sworn to administer the law and sheriffs are paid to execute the decrees of the courts, and where, in fact, every instrument of civilization is supposed to work for the common good of all citizens, that this matter was duly investigated, the criminals apprehended and the punishment meted out to the murderers. But this is a mistake; nothing of the kind was done or attempted.” She backs up this assertion with an account of what happened six months later when an investigator attempted to find out how the matter had been settled. The investigator, George Washington of Chicago, Illinois, who had written to Lonoke County sheriff S. S. Glover, received the following reply: “DEAR SIR:—The parties who killed Hamp Briscoe (sic) February the ninth, have never been arrested. The parties are still in the county. It was done by some of the citizens, and those who know will not tell.”

The Arkansas Gazette tells a slightly different story, however. According to an article published on February 12, five days after the murders, Governor James Philip Eagle had sent a letter to Sheriff Glover “asking for a statement of the facts in the case, and that steps be taken to prevent further trouble.” Glover was not available, but his deputy, T. J. Tygart, replied that as soon as he (Tygart) heard about the killings, he and the coroner went to Keo, where they learned that two men, dressed in women’s clothes and bonnets, “bursted the door down and covered the guards with their pistols, told them to ‘get out’ and began immediately to shoot the prisoners and continued to shoot until they had killed all three of them.” The guards were described as three white men and two African Americans, who reportedly never saw the killers’ faces because the killers wore masks and bonnets. The local justice of the peace had already held an inquest, and the deputy stated that “there seems to have been a very extensive investigation made, and the verdict was that the parties were killed by unknown parties.” Tygart reported that, by the time he left, everything was quiet. He himself attempted to discover who the killers were but “could not get anything that would lead to anything to make a charge against any one. The matter was well planned and kept.”

For additional information:

“Assassinated in Arkansas.” Omaha Daily Bee, February 13, 1892, p. 2.

“The England Killings.” Arkansas Gazette, February 12, 1892, p. 6.

“A Tale of Horror.” Arkansas Democrat, February 11, 1892, p. 1.

“Three Negroes Killed.” Arkansas Democrat, February 9, 1892, p. 1.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States. N.p.: 1895. Online at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14977/14977-h/14977-h.htm (accessed February 8, 2024).

“Wiped out the Family.” Wichita Daily Eagle, February 10, 1892, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Presbyterian College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.