calsfoundation@cals.org

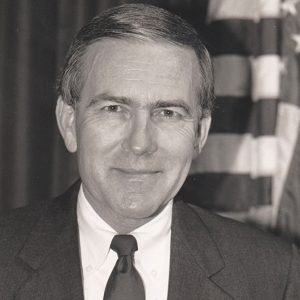

Tommy Franklin Robinson (1942–)

Tommy Franklin Robinson made a statewide name for himself as a controversial Pulaski County sheriff, won a seat in Congress as a Democrat, switched to the Republican Party while in office, and then lost in a 1990 Republican primary race for governor of Arkansas.

Tommy Robinson was born on March 7, 1942, in Little Rock (Pulaski County), an only child. His father, Hoover, was a fireman, and his mother, Esther, was a state worker. He grew up in the Rose City area of North Little Rock (Pulaski County), with future Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones as a childhood friend. He later married Carolyn Barber of Scott (Pulaski and Lonoke counties); they have six children.

Robinson graduated from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) with a BA, majoring in criminal justice with a minor in political science. He then served four years in the U.S. Navy, after which he started a career in law enforcement. He worked for the Arkansas State Police (two stints), the North Little Rock Police, and the U.S. Marshal Service (he guarded some Watergate figures and was at the 1973 American Indian Movement uprising at Wounded Knee, South Dakota). He became director of public safety at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) campus, then Jacksonville (Pulaski County) police chief, and later director of public safety for the State of Arkansas. He quit to make a successful run for Pulaski County sheriff in 1980.

As sheriff, Robinson soon captured the attention of statewide news media with glib comments and attention-getting actions. Plagued with jail escapes and overcrowding in July 1981, Robinson blamed the problems on a backlog of prisoners due to be sent off for state prison terms. He had a group of them chained to a fence outside a prison facility at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). Suspecting the Arkansas State Police might try to return them, he called out all of his deputies for emergency duty that night to ring the block around his jail. He told reporters at the scene that he would deputize them and issue them weapons to help fight the State Police. (The State Police did not show up at his jail, and the prisoners were taken elsewhere.)

To fight convenience-store robberies, he started “Robinson roulette,” in which deputies with shotguns would rotate in hiding at participating retailers. He declared the program a success in rural Pulaski County, but a clerk was shot to death in a participating store in Little Rock.

In just one day in March 1982, Robinson had the county judge and the comptroller arrested on misdemeanor charges, and then the sheriff himself was jailed for contempt by a federal judge. These arrests came after Robinson ejected a special master named by the federal judge to oversee the jail. The county judge and comptroller were arrested after they refused to release money for the sheriff without the master’s approval.

Robinson drew much more publicity during the investigation and trials in the hit-man slaying of Alice McArthur in her west Little Rock home in July 1982. Little Rock police made three arrests in the case—Mary Lee Orsini of North Little Rock and two men she persuaded to pose as floral delivery men to shoot McArthur. Even though the prosecutor told him he did not have a case, Robinson arrested Alice McArthur’s husband, attorney William McArthur, after interviewing Orsini. William McArthur had represented Orsini in the investigation of her husband’s shooting death. The sheriff publicly feuded with the prosecutor and the Little Rock police at length over the case. Robinson even arrested McArthur a second time on an alleged plot to have Robinson himself killed in January 1983. However, the case fell apart quickly. It turned out that McArthur was seen by judges, prosecutors, journalists, and others at the Pulaski County Courthouse at the time the plot supposedly was hatched in Malvern (Hot Spring County). The young men Robinson arrested in the plot testified it was “a stupid joke.”

Robinson had two key prosecution witnesses arrested in October 1983 just before Orsini was to go to trial in the slaying of her husband. (She was found guilty at trial, but that was overturned on appeal.) A grand jury cleared William McArthur in his wife’s slaying. Even Orsini eventually said in a 2003 prison interview shortly before she died that the lawyer had no role in killing his wife and that she had killed her husband herself.

Robinson was also involved in the arrest and trial of Barry Lee Fairchild, who was eventually convicted of murder and executed by the State of Arkansas. Fairchild—who had an IQ in the low sixties (in the range considered mentally challenged)—had confessed during questioning following his arrest to the murder of Greta Mason in Lonoke County in 1983. During his trial, Fairchild recanted his testimony, claiming that Sheriff Robinson and Major Larry Dill beat and threatened him during his questioning, forcing a false confession. A former deputy sheriff also claimed to have seen Fairchild and his brother Robert tortured by Robinson and other officers. The jury found Fairchild guilty based on his confession; after years of appeals and further hearings, Fairchild was executed in 1995.

The sheriff still managed to have widespread popular support. He was elected to Congress in 1984 as a Democrat representing the state’s Second Congressional District. He was named to the House Armed Services Committee and to the Education and Labor Committee. During his three terms, Robinson sponsored six bills in Congress, none of which ever left to committees to which they were assigned. He frequently voted with the Republican administration of President Ronald Reagan. During his third term, he switched to the Republican Party—a significant enough event at the time that President George H. W. Bush marked it with a White House press conference.

From there, with the apparent encouragement of national Republican Party chairman Lee Atwater, he campaigned for the Republican nomination for governor. (Atwater reportedly spotted Governor Bill Clinton as a potentially troublesome rival for Bush and saw Robinson as a candidate who could fight a rough enough campaign to disable Clinton politically, if not defeat him.) In a tough contest, Robinson lost the nomination to Sheffield Nelson, a businessman and another recent convert to the GOP. The totals showed that the vote in the state’s Republican primary was unusually high, particularly in Pulaski County, where there were twice as many voting in the Republican gubernatorial primary as had voted in the 1988 GOP presidential primary. (Robinson lost in Pulaski County by 8,321 votes and statewide by 8,127 votes.) As part of a stop-Robinson movement, Democrats had reportedly switched over to vote in the Republican primary in sufficient numbers to provide the margin for Robinson’s defeat.

Robinson left Congress in 1991, but not without more controversy. In a scandal over congressmen overdrawing their accounts in a bank operated for the U.S. House of Representatives, Robinson was reported in 1992 as the top offender. He had 996 overdrafts, totaling more than $250,000.

Robinson, who had a farm in Brinkley (Monroe County), tended to his crops and business interests until the 2002 race for Congress. In 1999 Governor Mike Huckabee placed Robinson on the Arkansas Pollution Control and Ecology Commission, and the next year placed him on the State Parole Board. In 2002, he ran in the First Congressional District, which includes Brinkley. He lost to the incumbent, Marion Berry, a conservative Democrat. Huckabee put Robinson on the Arkansas Rural Development Commission in 2005.

In 2006, Robinson was jailed for five days for fighting with a creditor. In 2007 and 2008, he was cited for contempt in bankruptcy court. Robinson later became the managing partner of Robinson Group LLC, based in Brinkley. It is a partnership of political consultants and federal and state lobbyists.

For additional information:

Bentley, George. “Robinson Arrests Beaumont, Comptroller; Then He’s Jailed.” Arkansas Gazette, March 23, 1982, pp. 1A, 4A.

Bentley, George, Lamar James, and C. S. Heinbockel. “2 Key Witnesses Face Charges of Perjury.” Arkansas Gazette, October 19, 1983, pp. 1A, 7A.

Cole, Nancy. “Robinson Guilty of Contempt, Jail-Bound.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 11, 2008, pp. 1D, 2D.

Conason, Joe, and Gene Lyons. The Hunting of the President: The Ten-Year Campaign to Destroy Bill and Hillary Clinton. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

Heinbockel, C. S., and George Bentley. “Judges Report They Saw McArthur; Sheriff Isn’t Fazed.” Arkansas Gazette, February 1, 1983, pp. 1A, 6A.

Nelson, Rex. “Tommy Robinson at 75.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 3, 2018, p. 7B.

“Tommy Franklin Robinson.” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=R000354 (accessed January 30, 2024).

Charles S. Heinbockel

Little Rock, Arkansas

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Gallery Pass

Gallery Pass  Tommy Robinson

Tommy Robinson  Tommy Robinson at Parade

Tommy Robinson at Parade  Tommy Robinson Roast

Tommy Robinson Roast  Tommy Robinson

Tommy Robinson  Tommy Robinson Pin

Tommy Robinson Pin

Tommy Robinson should be in jail. He is complicit in putting an innocent man to death.

I wish Mr. Robinson could be Pulaski County Sheriff. He did a good job.