calsfoundation@cals.org

Smallpox

Smallpox is an infectious disease characterized by the formation of a rash and blisters across the face and extremities. With an overall mortality rate of approximately thirty-five percent, it was one of the most feared diseases in the world before coordinated vaccination efforts resulted in the disease being eradicated in 1979. In Arkansas, smallpox greatly affected Native Americans and played a role in the creation of later public health initiatives.

Smallpox was first introduced into North America by European explorers, who brought to the New World any number of diseases to which Native Americans had not previously been exposed. Some historians estimate that perhaps ninety percent of the indigenous population of the Americas may have been killed by diseases brought by Europeans, with smallpox being the chief culprit among them. Indeed, an outbreak in Massachusetts Bay between 1617 and 1619 killed an estimated ninety percent of the Indians residing there, while similar outbreaks, if not as fierce, weakened numerous other tribes, most notably the Cherokee. British soldiers in 1763 even used smallpox as a weapon, giving to the Indians besieging Fort Pitt in Pennsylvania blankets tainted with smallpox with the hopes of infecting them.

The disease may have been introduced into what is now Arkansas during the expedition of Hernando de Soto in 1541–1542. The chroniclers of the de Soto expedition described a vast array of indigenous communities they encountered. By contrast, the Marquette-Joliet Expedition of 1673 found Arkansas largely depopulated, save for a handful of Quapaw villages, thus leading some historians to conclude that diseases such as smallpox—introduced either by de Soto and his men or perhaps spreading to Arkansas from points east—may have decimated the native population, though there is no solid proof for this conjecture. The Quapaw were later hit by smallpox around 1698, with the result that their population dropped from between 3,500 and 7,500 to a low of between 800 and 1,200.

The lack of personal mobility and a dearth of large population centers in Arkansas’s territorial and early statehood years meant that smallpox outbreaks could remain rather limited in scope. However, during the Civil War, smallpox easily spread in the close quarters of military encampments. A December 6, 1862, letter from Private Elisha Stoker of Company H, Eighteenth Texas Volunteer Infantry, records an outbreak near Brownsville, in what is now Lonoke County, and notes that fear of the disease led many soldiers to consider deserting. At the 1863 Skirmish at Taylor’s Creek, the spread of smallpox in Confederate ranks prevented Colonel Archibald Dobbins from completely routing the Federal forces he had on the run. A similar situation persisted among railroad, logging, and mining camps across the state, as exemplified by the 1879–1880 outbreak among railroad camp inhabitants near Winslow (Washington County). Likewise, during the Spanish-American War, Arkansas soldiers who had to endure the miserable conditions of the camp in Chickamauga Park in Georgia contracted smallpox and even brought back to Arkansas new strains of the disease.

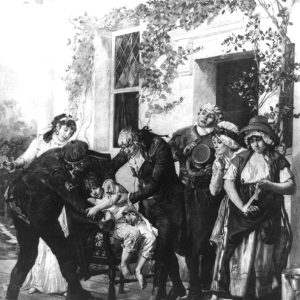

Inoculation against the smallpox disease may have been practiced as early as AD 1000 in India. Early inoculation efforts often consisted of exposing a healthy individual to a dried smallpox scab, with the result that his or her body would produce antibodies in reaction to the weakened or dead virus. In the late 1700s, English doctor Edward Jenner discovered that inoculating an individual with cowpox made that person immune also to smallpox—a procedure that was much safer than the previous procedures. Despite this long history of proven methods for smallpox prevention, Arkansas’s legislators rejected mandating inoculations, even after an 1895 outbreak in Hot Springs (Garland County) created bad headlines for the state across the country, and even after an 1897 outbreak in Salem (Fulton County) spread quickly across the state, resulting in 7,000 to 10,000 cases yearly. Prominent physician W. H. Abington went so far as to claim that inoculations were ineffective against the disease.

The 1897 outbreak did, however, temporarily revive the defunct State Board of Health, which was made permanent in 1913. Though vaccinations were becoming increasingly common, outbreaks did still occur. On February 8, 1913, the Jonesboro Evening Sun reported an outbreak of 300 cases of smallpox in the town of Marmaduke (Greene County), though the disease was reportedly in such a mild form it was first thought to be chicken pox. In 1914, an outbreak in Elm Springs (Washington and Benton counties), spread by a local family just returned from Mexico, infected twenty-six and killed ten. In 1916, Arkansas became the first state in the Union to introduce a compulsory vaccination program for all children starting school. Despite this, smallpox still occasionally appeared in the state, with five cases reported in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) in 1922. Two legal challenges to the vaccination mandate in the 1930s failed, and smallpox all but disappeared from the medical and cultural landscape of not just Arkansas but also the whole country. Due to coordinated efforts against the disease worldwide, smallpox was completely eradicated, with the last known case occurring in 1978.

For additional information:

Scholle, Sarah Hudson. The Pain in Prevention: A History of Public Health in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Department of Health, 1990.

“Smallpox in Russellville.” Pope County Historical Association Quarterly 42 (June 2008): 11–15.

Young, Frank B. “Report of an Epidemic of Smallpox in Washington County.” Flashback 7 (November 1957): 3–4.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Sanitation

Sanitation First Inoculation

First Inoculation  Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner  Smallpox in Texarkana

Smallpox in Texarkana

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.