calsfoundation@cals.org

Shape-Note Singing

Shape-note singing is a choral tradition in which geometrical shapes and a corresponding syllable are assigned to each note in a musical scale. The tradition began in late eighteenth-century New England, and it is one of the earliest forms of distinctly American music. In Arkansas, shape notes are found in multiple singing traditions, including both the four- and seven-note methods. This type of singing also had a social role in rural communities in Arkansas, which often held all-day events featuring shape-note singing.

Shape-note singing is largely used for religious music, although it does occasionally appear in secular music. Conventional shape-note singing preserves elements of earlier European music, such as basic harmony, melodies, and performance practices. Shape notes were developed in order to provide an accessible way for singers with little or no literacy skills to read musical notation. Settlers carried the tradition with them as they migrated from colonial America into other parts of the country, including the Southeast and eventually the Ozark Mountains. Itinerant “singing masters” typically led classes at a local church or schoolhouse during months with less agricultural work, after which students possessed the skills necessary to sight-read vocal music.

Shape notes first appeared in print in William Little and William Smith’s The Easy Instructor, published in 1801. Their book used four syllables for the seven notes on the scale. Little and Smith’s system assigns a right triangle for fa, an oval for sol, a rectangle for la, and a diamond for mi. Four-syllable systems may also be called fasola singing.

The Easy Instructor’s publication sparked a boom in the development of shape-note systems, and because publishers were unable to secure patents for the notations, multiple variations of these systems appeared. The individual notation methods that emerged from the publishing war spurred a variety of traditions using shape notes, some of which are still sung in Arkansas today. Two systems of shape-note singing were taught in Arkansas, one using four shapes and the other using seven.

Sacred Harp is perhaps the most popular four-shape system to emerge from this period. The book from which it received its name, The Sacred Harp, was first printed in 1844. Sacred Harp adheres to the traditions established by earlier singers. The music is performance based, meaning that it is sung for the enjoyment of the singers, not for an audience. The music has four parts, arranged for alto, tenor, treble, and bass. Singers assemble in what is known as a “hollow square,” facing inward. Altos and tenors face one another on two opposite sides of the square, while the treble and bass singers face each other on the remaining sides. This arrangement places the song leader in the center of the square, where the fullest sound may be heard.

Song leaders typically lead one to two songs to allow for each participant to experience the sound in the square’s center. Each song is sung twice. On the first run, participants sing only the syllables as they learn their parts, and they sing the lyrics on the second run. Leaders keep time with a simple up-down movement of one hand, while the other hand holds a songbook. For experienced song leaders who do not require a book, the unused hand is sometimes held behind the back.

In 1846, Jesse B. Aikin added three additional shapes to the existing four-shape methods, producing a seven-shape system that is also known as doremi or convention singing. Aikin’s book, Christian Minstrel, set the standard for singers using seven-shape methods. As is the case in Sacred Harp, gospel shape-note music is written for four parts, but the latter’s inclusion of instrumental accompaniment casts it as the more progressive of the two. Gospel publishers adopted Aikin’s system, and it became a popular form of shape-note singing in Arkansas.

Probably the most well-known Arkansas publisher of shape-note music was the Hartford Music Company, founded in 1918 by Eugene Monroe (E. M.) Bartlett. The Jeffress/Phillips Music Company in Crossett (Ashley County) has been publishing shape-note music since 1945.

The gospel tradition also promoted shape-note literacy through singing schools. Publishing companies such as the Stamps-Baxter Music Company, which had a satellite office in Pangburn (White County), employed traveling instructors to teach from their books, so it was not uncommon for a singing school to devote itself to a single publisher or songbook. Since 1947, students at the Brockwell Gospel Music School in Brockwell (Izard County) have learned the seven-shape tradition as part of its music curriculum. Instruction in the seven-shape gospel tradition is still available there at a two-week class held each June. While the number of gospel shape-note publishers dwindled in the twentieth century, new music is still introduced each year.

As late as the mid-twentieth century, shape-note singing thrived in rural Arkansas communities where the population’s primary access to music was through performance. Shape-note “singings” served a social function in Arkansas communities during the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Participants gathered for all-day events that typically included several hours of singing, socializing, and a potluck meal. Such events still are held in present-day Arkansas, as with the Old Folks’ Singing event held in Tull (Grant County) every year. A number of conventional shape-note groups exist in Arkansas today, including the Shiloh Sacred Harp Singers, who host a regular singing on the second Sunday of each month at the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History in Springdale (Washington and Benton counties).

The number of shape-note singers in Arkansas declined in the latter half of the twentieth century, but scholars note a resurgence in the Sacred Harp tradition. Propelled by the introduction of a national convention in 1980, Sacred Harp now appears in cities and college campuses across the United States, as well as in Canada and Europe.

For additional information:

Deller, David. “The Songbook Gospel Movement in Arkansas: E. M. Bartlett and the Hartford Music Company.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Autumn 2001): 284–300.

Floyd, Anna. “History of the Brockwell Gospel Music School.” Unpublished manuscript. Brockwell Gospel Music School, Brockwell, Arkansas.

Old Folks’ Singing Planning Committee. Blest Be the Tie that Binds: 125 Years of Old Folks’ Singing in Tull, Arkansas: 1885–2010. Benton, AR: 2010

Leslie Hassel

Fort Smith, Arkansas

Music and Musicians

Music and Musicians Brockwell Gospel Music School

Brockwell Gospel Music School  Hartford Music Company and Hartford Music Institute

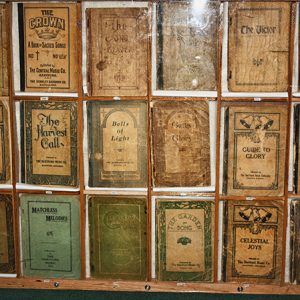

Hartford Music Company and Hartford Music Institute  Hartford Music Company Song Books

Hartford Music Company Song Books  Jimmy Powers

Jimmy Powers  The Tulltones

The Tulltones

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.