calsfoundation@cals.org

Prairie Grove Campaign

Spring 1862 was one of despair for Confederate Arkansas following the defeat at Pea Ridge (Benton County) and the capture of Helena (Phillips County) by the victorious Union army under the command of Major General Samuel Ryan Curtis. The arrival of Major General Thomas C. Hindman as commander of the Trans-Mississippi region in May brought a glimmer of hope, as he immediately began rebuilding the army protecting the state, encouraged the use of guerrilla warfare against the Union invaders, and established Confederate factories to provide much-needed supplies. Throughout the summer and fall, the armies in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas jockeyed for position and skirmished with each other, culminating with the Prairie Grove Campaign, which determined the fate of Missouri and northwest Arkansas.

After a snowstorm in late October 1862, the opposing forces settled in for the winter, with Major General Hindman and the Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi establishing their camps along the south side of the Arkansas River near Fort Smith (Sebastian County). Union Major General John M. Schofield, commander of the Army of the Frontier, moved two of his three divisions to the vicinity of Springfield, Missouri, while leaving one division under the command of Brigadier General James G. Blunt in northwest Arkansas. The arrival of milder weather and drier roads encouraged Hindman to send his cavalry under the command of Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke to northwest Arkansas. Blunt learned of the approaching Confederate cavalry and marched south, attacking the Southern force at Cane Hill (Washington County) on November 28, 1862.

The 2,000 Confederate troops under Marmaduke were no match for the 5,000 soldiers and thirty cannon under Blunt. The Engagement at Cane Hill became a nine-hour running retreat by the Southern forces covering twelve miles of rugged, rocky, forested ground. Casualties were light on both sides—about forty for the Union side and slightly more for the Confederates. Afterward, Blunt decided to remain in the fertile Cane Hill region gathering supplies for winter.

Hindman’s Confederates crossed the Arkansas River and marched north to attack Blunt’s command. The Southern army had about 12,000 well-armed but hungry soldiers and twenty-two cannon, compared with the Federal force of 5,000 men and thirty cannon. The Confederates made slow progress through the Boston Mountains. Learning of the Southern threat to his command, Blunt telegraphed for reinforcements, which were almost 120 miles away near Springfield. Answering the call for help was Brigadier General Francis J. Herron, who immediately placed the two divisions of the Army of the Frontier under his command on a forced march covering about 110 miles in three and a half days. This was one of the most outstanding marches by any army during the Civil War.

On December 6, skirmishing broke out between Blunt’s Union pickets on Reed’s Mountain and Marmaduke’s Confederate cavalry in front of Hindman’s army. The Federal troops fell back toward Cane Hill while the Southern forces occupied the farm of John Morrow in the Cove Creek valley. The Confederate high command was at Morrow’s house that evening, making plans to attack Blunt in the morning, when word arrived that Union reinforcements were at Fayetteville (Washington County). Hindman decided to flank Blunt’s command and attack the troops under Herron between Cane Hill and Fayetteville. The stage was set for the Battle of Prairie Grove.

The Union’s Seventh Missouri Cavalry and the First Arkansas Cavalry clashed with the Confederate cavalry at dawn December 7 about a mile south of the Prairie Grove church. The Federal cavalry retreated toward Fayetteville in confusion as the superior Southern force overwhelmed it. The chaotic flight continued until the troops reached the main body of Herron’s force marching southwest from Fayetteville. The Confederate cavalry skirmished with the Union infantry and artillery and fell back toward the Illinois River and the Prairie Grove (Washington County) ridge, where the Southern infantry and artillery were in position for a fight.

When Herron arrived at the Illinois River, he sent a small force across to assess the situation. Confederate artillery opened fire and forced a withdrawal. Learning of a northern ford, the Federal troops cut a road through the brush. Captain David Murphy’s Company F, First Missouri Light Artillery, crossed the river and positioned six ten-pounder Parrott rifles atop Crawford’s Hill and opened fire. The Confederates concentrated their artillery fire on the Federal cannon, allowing the rest of Herron’s command to cross at the main ford. Shortly, all of the cannon in the Union army were blasting the wooded ridge, where the smoothbore cannon of the Southern batteries were quickly silenced.

A Union infantry charge up the hill by the Twentieth Wisconsin and Nineteenth Iowa Infantry regiments near the home of Archibald Borden captured the cannon of Captain William Blocher’s Arkansas Battery for a short time before being driven back by a Confederate counterattack. The Southern assault melted away under the withering fire of the Union artillery firing case shot and canister, consisting of numerous lead and iron balls pouring through the Confederate lines. Another Union attack up the hill by the Thirty-seventh Illinois and Twenty-sixth Indiana Infantry regiments recaptured Blocher’s battery before being forced to retreat down the hill.

Two cannon shots announced the arrival of Blunt’s command from northwest of the Prairie Grove ridge at about 2:30 p.m. with two cannon shots. The fighting shifted to the western half of the valley and high ground as Federal troops threatened the Confederate left flank. After his men skirmished for some time in the woods without gaining ground, Blunt ordered them to withdraw into the valley, where his artillery was positioned. The Confederates launched a final counterattack into the valley under the command of Brigadier General Mosby M. Parsons, but the accurate and destructive fire of the Union artillery thwarted the attack.

Under the cover of darkness, the Confederates wrapped blankets around the wheels of their cannon and withdrew. Despite freezing temperatures, the Union troops slept with their weapons ready on the cold, damp ground without enough tents and blankets and with no campfires. Both armies lost similar numbers—about 2,700 soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing. While a tactical draw, the Battle of Prairie Grove was a strategic Union victory.

While the Confederates returned to their camps south of the Arkansas River near Fort Smith, the Union army sent its wounded to Fayetteville and camped on the battlefield. Blunt, Herron, and about 8,000 infantry, cavalry, and artillery marched south toward Van Buren (Crawford County) on December 27, arriving the next day. They surprised the Confederates and captured four steamboats, a ferry, and other military goods. After taking what they could, Federal troops burned the steamboats, the ferry, and other Confederate supplies in Van Buren. This raid included a brief artillery duel across the Arkansas River with few casualties. As 1862 ended, the Army of the Frontier returned to camp at Prairie Grove and Cane Hill before heading north in January. After the Prairie Grove Campaign’s strategic success for the Union, never again would a Confederate army march into northwest Arkansas or southwest Missouri, although Southern cavalry raids and guerrilla actions would continue to plague the region.

For additional information:

Banasik, Michael E. Embattled Arkansas: The Prairie Grove Campaign of 1862. Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing Company, 1996.

Christ, Mark K., ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Montgomery, Don, ed. The Battle of Prairie Grove. Prairie Grove, AR: Prairie Grove Battlefield Historic State Park, 1996.

“The Prairie Grove Campaign: A Sesquicentennial Retrospective.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 71 (Summer 2012).

Sallee, Scott E. “The Battle of Prairie Grove: War in the Ozarks, April ’62–January ’63.” Blue & Gray Magazine 21 (Fall 2004): 6–23, 45–50.

Shea, William L. Fields of Blood: The Prairie Grove Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

———. War in the West: Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove. Abilene, TX: McWhiney Foundation Press, 2001.

Don Montgomery

Prairie Grove Battlefield Historic State Park

Battle of Prairie Grove

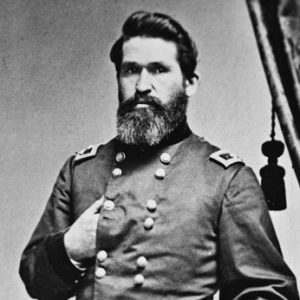

Battle of Prairie Grove  James Blunt

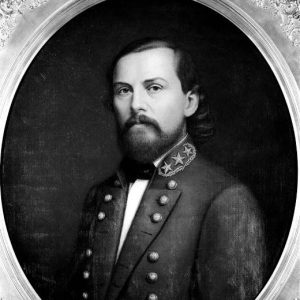

James Blunt  Thomas Hindman

Thomas Hindman

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.