calsfoundation@cals.org

Prairie County

| Region: | Southeast |

| County Seats: | Des Arc, DeValls Bluff |

| Established: | November 25, 1846 |

| Parent Counties: | Monroe, Pulaski |

| Population: | 8,282 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 647.52 square miles (2020 Census) |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

2,097 |

8,854 |

5,604 |

8,435 |

11,374 |

11,875 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

13,853 |

17,447 |

15,187 |

15,304 |

13,768 |

10,515 |

10,249 |

10,140 |

9,518 |

9,539 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8,715 |

8,282 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

6,964 |

84.1% |

| African American |

925 |

11.2% |

| American Indian |

23 |

0.3% |

| Asian |

21 |

0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

3 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

44 |

0.5% |

| Two or More Races |

302 |

3.6% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

145 |

1.8% |

| Population Density |

12.8 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$42,660 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$25,789 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

14.8% |

|

Prairie County, located in central Arkansas, has two county seats, Des Arc and DeValls Bluff. An important agricultural center, Prairie County has a rich history as the state’s throughway for mail routes, steamboats, and trains.

European Exploration and Settlement

European exploration of the area began as early as the late seventeenth century. While the area became intermediately occupied by both the Spanish and French, the county remained vital to trade expeditions. The earliest recorded Euro-American settlement of Prairie County is debatable but can be placed in the late eighteenth century.

French traders traveled up and down the White River in the early 1700s. Bear oil and skins, abundant in this area at the time, were sought-after commodities in the New Orleans markets. The rivers were the highways of this early era. Early maps identify the White River as “Eau Blanche” and “Riv. Blanche” (“blanche” being the French word for white).

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Des Arc was the earliest settlement; Creoles named Watts and East are credited as being Des Arc’s first residents, arriving around 1810. The name “Des Arc” itself is a French term translated to mean “bow,” “bend,” or “curve.” On various early documents, the town of Des Arc is referenced as Des Ark, Francisville, Des Arcs, des Argues, Desarc, des Arques, Desare, McNulty’s Bluff, Des Arcs Bluffs, and Dezark Bluff. It was not until after the Civil War that the name Des Arc was accepted universally.

When Arkansas became a state, the area that is today Prairie County was first a part of Arkansas, Pulaski, Monroe, St. Francis, and White counties. On November 25, 1846, Arkansas governor Thomas S. Drew approved the legislative act creating Prairie County, so named for its dominant characteristic, the Grand Prairie. At the time, the boundaries extended into nearly all of present-day Lonoke County. Brownsville was designated as Prairie County’s first county seat in 1846. A wood frame courthouse was erected, which lasted until a fire destroyed it on September 16, 1852. However, the building was rebuilt, and the seat remained in Brownsville until 1868. In 1873, Lonoke County was carved from Prairie County.

Des Arc was a flourishing river town prior to the Civil War. Timber for homes was plentiful. Fish and game were abundant, and the population grew rapidly. Selling wood to power the steamboats and rafting timber along the river were viable occupations. The Butterfield Overland Mail route in the late 1850s was key in the development of Des Arc. The city had the fortune of being on the direct route from Memphis, Tennessee, to Fort Smith (Sebastian County). Thus, the mail and any travelers had to go through Des Arc.

The census of 1850 for Prairie County shows a population of slightly more than 2,300 people, including 273 slaves. In 1860, there were 2,839 slaves in the county with a white population of 6,015. There were at least 125 slave owners in Prairie County during the time period leading up to the Civil War, and the most any one person owned was eighty-nine slaves. Cotton is one of the major factors that led to this significant increase in population, as significant manual labor was needed to produce the cotton crop.

The Presbyterians established the first church in Prairie County, the Wattensas Presbyterian Church, which was organized by 1848 in the String Town community.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

Prairie County’s white residents supported the South wholeheartedly during the Civil War. The city of Des Arc enumerated a population of about 2,000 at the beginning of the war. During the war, the city was largely destroyed—some of the buildings were burned, and others were moved by the United States army to DeValls Bluff. At war’s end, the population of Des Arc numbered around 400.

At the beginning of the Civil War, DeValls Bluff was home to a store, a dwelling house, and a boat landing. The earliest action in the county was fought on July 6, 1862, as Federal troops moved across the state after the Battle of Pea Ridge. In the fall of 1863, General Frederick Steele moved from Clarendon (Monroe County) and occupied DeValls Bluff. From then until the close of the war, DeValls Bluff was a supply base for the Federal army. War materials were brought from Northern states down the Mississippi River and then up the White River and stored in warehouses near the river. At DeValls Bluff, supplies could be shipped to what is now North Little Rock (Pulaski County) and other points west on the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad, as the railroad was not contiguous from Little Rock (Pulaski County) to Memphis on account of Delta swamplands. Large numbers of soldiers were stationed at DeValls Bluff, and many of them fell victim to the “Clarendon shakes” (i.e., malaria), which was prevalent in the area.

The importance of DeValls Bluff and the White River to the Federal war effort led to numerous engagements in the county. Union troops constructed a number of fortifications around the settlement, naming at least one Fort Lincoln. Engagements near DeValls Bluff were fought on December 1, 1863; May 22, 1864; and December 13, 1864. Other engagements in the county were at Des Arc Bayou, Ashley’s Station, and Hickory Plains.

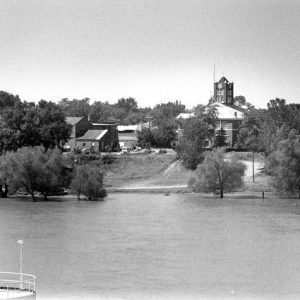

The next county seat was located in DeValls Bluff from 1868 through 1875. In 1875, the county seat was moved to Des Arc. Then, in 1885, the county was divided into northern and southern districts with courthouses in both Des Arc and DeValls Bluff. This division was due to the frequent flooding along the White River, which divided the county and made it impossible for citizens in the southern half of the county to pay their taxes on time.

The Memphis and Little Rock Railroad was completed through the Surrounded Hill area in 1871. That same year, a rail line was laid through what is now Brasfield, which grew up around it. The railroad caused DeValls Bluff to lose its importance as a shipping center, and its population declined dramatically. Industries in the county after the war included fishing, timber, steamboat trade, railroading, and farming. Eventually, industries setting up shop in the county included button factories (using mussel shells from the White River), a boat oar factory, a cannery, stave mills, hay production, cotton gins, a flour mill, a nursery, an ice factory, and dairies. In 1882, the Wattensas Farmers’ Club was organized at the McBee home. The club worked toward the betterment of farmers throughout the county. Though ineffective at the time, the club quickly grew into a farming movement known as the Agricultural Wheel, which greatly impacted farming and politics in all of Arkansas.

The town of Slovak was created in November 1894 when Peter V. Rovnianek, F. J. Pucher, and members of forty other families formed the Slovak Colonization Company and bought 3,600 acres of land from P. R. Peterson. The settlers hoped to recreate the European homeland communities they remembered. The families, for the most part from Slovakia and not fluent in English, scratched out a 160-acre town amid head-high prairie grasses.

Other communities in the county founded in the late nineteenth century include Ulm, Biscoe, and Hazen.

Several incidents of extrajudicial racial violence occurred in the county in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1869, Jeff Johnson lost his life after being accused of attacking a white woman. Accused of killing a white girl in 1881, Henry Smith lost his life at the hands of a mob. George Bailey was killed after being accused of shooting a white bartender in 1909 in Biscoe.

Early Twentieth Century

In 1903, William H. Fuller brought the rice industry to the Grand Prairie. Slowly, rice became one of the major grains grown in this county. The silty loam soil proved itself to be excellent rice-growing ground.

In 1911, the Northern District courthouse in Des Arc once again burned, but the records were saved. The current courthouse was constructed in 1913.

During the Great Depression, many rural families relied upon the rivers and woods to provide food for their tables. Bartering became a way of life for local residents. Hazen resident Irene Robertson conducted hundreds of interviews with formerly enslaved people, their families, and older whites. These interviews were conducted as part of the Federal Writers’ Project, a government-sponsored effort to provide work for out-of-work authors and scholars.

After the Flood of 1927, dams were established along the White River in northern Arkansas to help control the flood waters along the lower section of the river. Ferries were in use locally until about 1927, when a massive suspension bridge was built. This suspension bridge was operational until the early 1970s, when the state funded an entirely new structure.

World War II through the Modern Era

During World War II, many Prairie County citizens were called to fight or obtained employment in the war industry, and the population noticeably declined. The Stuttgart Army Airfield was located in the county during the war, training thousands of glider pilots. After the war, many citizens remained farmers.

In 1969, the state legislature passed an act giving funding to the county to open up a museum in Des Arc. Today, this museum is known as the Lower White River Museum State Park. It documents a rich history of the town and the importance of the White River. During the first week of June, Des Arc hosts the annual Steamboat Days Festival.

A shrub known as Stern’s medlar was discovered in 1969 near Slovak. The rare plant is only known to grow in that area.

In the twenty-first century, agriculture remains as important to Prairie County as it was in the nineteenth century. Much of the existing industry in the area remains farm related, especially rice, soybeans, and cotton. One problem in the region stems from the exhaustion of the water supply. Both the Alluvial and Sparta aquifers have diminished through years of use. Efforts to provide agricultural enterprises in the county with sufficient water have led to the creation of the Grand Prairie Area Demonstration Project. Water is taken from the White River near DeValls Bluff and distributed across the area.

Famous Residents and Sites

Musicians James Calvin Minor and Fiddlin’ Bob Larkan are associated with the county. Numerous sites in the county are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including Wingmead, the Des Arc American Legion Hut, and the DeValls Bluff Waterworks.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Eastern Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1890.

Central Delta Historical Journal. Brinkley, AR: Central Delta Historical Society (1997–).

Sayger, Bill. A DeValls Bluff Remembrancer. N.p.: 1994.

———. An Eastern Arkansas Remembrancer. Parts 2, 4. N.p.: 2001, 2002.

———. A Grand Prairie Remembrancer. N.p.: 2000.

Sayger, Bill. Prairie County. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

Sickel, Marilyn Hambrick. Prairie County, Arkansas: Pioneer Family Interviews by W.P.A.–Federal Writers’ Project, 1936–37. DeValls Bluff, AR: Grand Prairie Research, 1989.

Marilyn Hambrick Sickel

DeValls Bluff, Arkansas

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.