calsfoundation@cals.org

Olyphant (Jackson County)

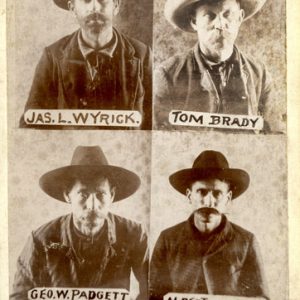

The community of Olyphant is most noted for being the site of the last train robbery in Arkansas. On November 3, 1893, eight men hijacked Iron Mountain passenger train No. 51, robbed the passengers, and murdered the conductor, William P. McNally. The robbers were tracked down, tried, and found guilty, and three were hanged in Newport (Jackson County) in the only known multiple execution in Jackson County history.

Olyphant is located on Highway 367 halfway between Newport, eight miles to the north-northeast, and Bradford (White County), eight miles to the south-southwest. Before the Civil War, Grand Glaise (Jackson County), a river port on White River, was the dominant community in the area and the second-largest town in the county. The Patterson Ferry, owned and run by James H. Patterson, crossed the White River at that point. Grand Glaise played an active role in the Civil War because of its strategic location on the river. Confrontations between Union and Confederate soldiers, such as the Skirmish at Stewart’s Plantation, took place in the area, which was on a main route for troops to travel from Jacksonport (Jackson County) to Searcy (White County).

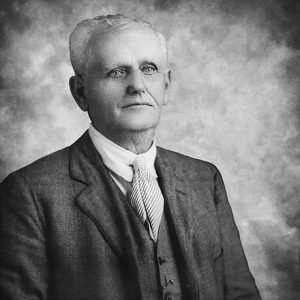

Olyphant was founded by Kentucky native Colonel Virgil Young (V. Y.) Cook, who became one of the wealthiest and most successful citizens of Independence and Jackson counties in the post–Civil War era. A Confederate veteran, he made his way to Grand Glaise in 1866 to engage in merchandising. In 1874, he moved to what is now Olyphant as an agent for the Cairo and Fulton Railroad, which had just been reorganized as the Cairo, Arkansas and Texas Railroad (CA&T), which later merged with the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railroad (commonly called the Iron Mountain). He also conducted a large and profitable mercantile business. During that time, he began to accumulate real estate in the Oil Trough Bottoms on the Upper White River in Independence County and elsewhere, eventually owning 8,000 acres of land in Jackson, Independence, Clay, and Greene counties. In 1874, Cook was appointed the first postmaster of Olyphant. The name of the depot and post office is thought to be derived from the name of railroad official John Olyphant. (This post office was replaced in 1960 with one designated Olyphant Rural Station; it closed in 1973.)

By 1895, Olyphant was a prosperous farm community with a population of fifty; it had a store and post office, a gin, a church, and a school. The railroad was important to the community for trade, commerce, and transportation. Logging was done in the surrounding hills, and several residents from the Olyphant area were involved in the lucrative collection of freshwater mussel shells on the White River to obtain decorative pearls and to supply button factories.

Olyphant School, established in the 1890s, had an enrollment of about twenty-five students for the 1931–32 school year, with Dykas Davis as its teacher. In 1946–47, the last year for the school, the enrollment had increased to around forty-five students. Olyphant’s students were split among Newport, Oil Trough (Independence County), and Bradford schools when the school was consolidated in the late 1940s.

The button business began to fade in the 1930s. In the 1920s, U.S. Highway 67 was constructed, bypassing Olyphant. Passenger and freight service stops were discontinued for Olyphant by the railroad in the 1960s. To some extent, the town ceased to operate around this time.

Olyphant has produced a few notable figures, including Lillian Nora Epps Brown, the daughter of Joseph Epps and Emma Epps. Lillian Epps Brown and her husband, Floyd B. Brown, founded the Fargo Agricultural School at Fargo (Monroe County) in 1920, operating it until 1949. The school was an African-American-owned and -operated boarding school with a flexible curriculum for black male and female students. Bobby Brown of Olyphant was a popular rockabilly performer of the 1950s and 1960s in the Newport area, often playing at the Cotton Club in Trumann (Poinsett County). He and his band recorded “Down at Big Mary’s House” in 1960, pressed by King Records in Cincinnati, Ohio. On tours, Brown backed up several famous recording artists.

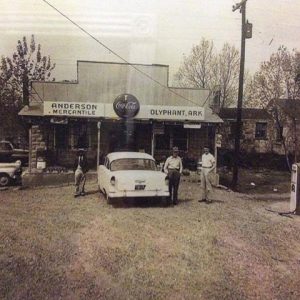

The store and gin are still standing in the twenty-first century but are closed. Large-scale farming is done in the bottomland, but soybeans, wheat, corn, and other cash crops now fill the landscape instead of cotton. Newport and Bradford are main shopping destinations, with a few traveling to Bald Knob (White County) and Searcy for dining, entertainment, and shopping. Many in the Olyphant area also work in those towns. Plans are under way to turn the office of the old gin into a museum and to reopen the old store.

For additional information:

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northeast Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1889.

Craig, Robert D. “Pearling, the Arkansas Klondike.” Stream of History 47 (August 2014): 3–16.

Hendrick, Wilma Fisher Camp. “Growing up in Olyphant.” Stream of History 55 (2022): 73–76.

Luker, Lady Elizabeth. “The Olyphant Train Robbery.” Stream of History 18 (November 1981): 2–12.

Matthews, Linda. “Cook-Morrow House.” Independence County Chronicle 55 (July 2014): 2–18.

Morrow, John P., Jr. “The Olyphant Train Robbery.” Independence County Chronicle 2 (October 1960): 3–14.

Kenneth Rorie

Van Buren, Arkansas

Anderson Mercantile

Anderson Mercantile  Nathan Anderson

Nathan Anderson  Virgil Y. Cook

Virgil Y. Cook  Jackson County Map

Jackson County Map  Olyphant Farming

Olyphant Farming  Olyphant Cotton Gin

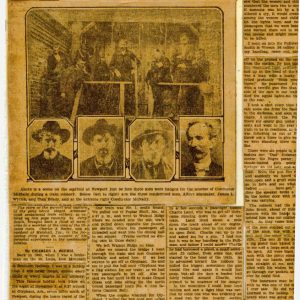

Olyphant Cotton Gin  Olyphant Train Robbers

Olyphant Train Robbers  Olyphant Train Robbery Account

Olyphant Train Robbery Account

My father, Robert E. Moore, was born in Jamestown in 1897. He told me that when he was growing up, they were still talking about the robbery. Sometime around 1917, he was living in Hillsboro, Texas. His usual schedule most days was to sit at the train station in Hillsboro and watch the trains and people, before going to work. One day, according to my dad, as he was watching the trains, a man sat beside him and asked if he was Bob Moore. My father said yes. The man asked if he had ever heard of the Olyphant Train Robbery. My dad said yes. The man asked if he was familiar with the Departee Creek swamps. My dad said yes and that he had hung a toenail all over those swamps while growing up. The man asked if he knew where the “big rock” was. My dad said yes. The man told him that if he could take him to that rock, he could dig up enough money to make them both rich. My dad told him that he would have to think on it some. Shortly afterward, he moved back to Arkansas and met my mom, and they got married. He forgot about the man. One day, he received a card from the man that said if he remembered their conversation at the train station in Texas, and if he was interested, to meet him in Little Rock on a certain day and at a certain place. He talked to Mom about it, and she said, “No! If you take him up there, he will knock you in the head and leave you for the wild hogs.” He didn’t go, and he never heard from the man again. In the mid-1970s, a friend and I went up there with metal detectors, looking for the rock. It was our thought to work in circles out around that rock, thinking that they buried something at night, so they were not far from the rock. We never found the “big rock.”