calsfoundation@cals.org

Lost Year

“The Lost Year” refers to the 1958–59 school year in Little Rock (Pulaski County), when all the city’s high schools were closed in an effort to block desegregation. One year after Governor Faubus used state troops to thwart federal court mandates for desegregation by the Little Rock Nine at Central High School, in September 1958, he invoked newly passed state laws to forestall further desegregation and closed Little Rock’s four high schools: Central High, Hall High, Little Rock Technical High (a white school), and Horace Mann (a black school). A total of 3,665 students, both black and white, were denied a free public education for an entire year which, increased racial tensions and further divided the community into opposing camps.

The Lost Year was the aftermath of the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School in 1957–58, the main event in a series that marked the well-known civil rights battle fought between the federal and state governments over the Arkansas implementation of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision. In that case, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously decided that racial segregation in public schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, overturning the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision which had originally brought legal segregation to American society and to educational facilities.

There was broad opposition to the Brown decision across the South. Southern state legislatures passed resolutions defying the desegregation decision, while white groups formed to defend segregation and fight those who attempted its implementation. In 1957, Governor Orval Faubus called out the Arkansas National Guard to prevent nine black students from entering Central High. President Dwight Eisenhower responded by sending federal troops (the 101st Airborne Infantry) and federalizing the National Guard to give the students protected entrance to the school. Desegregation seemed to be in place, the school year was completed, and a senior class graduated. However, Arkansas segregationists had other plans.

Three important events came together in the summer of 1958 that set up the Lost Year. First, the Little Rock School Board requested from the federal court system a delay in further implementing desegregation at Central High. Federal District Judge Harry Lemley granted a delay until January 1961. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) immediately petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court for an emergency order to overturn the delay granted by Lemley. These two court cases threw Little Rock’s desegregation back to the courts. Second, Faubus sought the Democratic nomination as governor for a third term. Faubus carried all seventy-five counties in the summer primary and felt assured of voter approval in the fall election. The third event was Faubus’ call for an extraordinary session of the Arkansas General Assembly on August 26, 1958, which passed a series of laws to forestall desegregation. Among the sixteen bills was Act 4, which allowed the closure of any school threatened with racial integration. Another bill, Act 5, allowed state monies to follow any displaced student to the school of his choice, whether privately or publicly funded.

When the U.S. Supreme Court met in special session in September 1958 (regarding the Aaron v. Cooper petitions), they ordered the immediate integration of Little Rock Central High on September 12 and said that Little Rock must continue with its desegregation plan. The same day, Faubus signed into law all the bills passed by the Arkansas General Assembly. He closed all four high schools in Little Rock beginning on Monday, September 15, interrupting the education of nearly 4,000 students and disrupting as many households and families. Faubus’s action not only locked students from their classrooms but locked 177 teachers and administrators in the schools, where they had to fulfill their contractual obligations and appear for work, despite the empty classes. Most were soon used as substitutes in junior high and elementary schools.

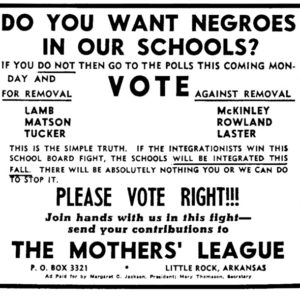

The newly passed law, Act 4, required voter approval. Faubus invoked the new law only for Little Rock high schools because those were the ones threatened with desegregation at that moment, so the vote was only in Little Rock. On September 27, ballots for reopening closed schools read: “For racial integration of all schools within the Little Rock School District,” and by a three-to-one margin, voters kept schools closed. The wording of the ballot and the timing of the election on a Saturday morning were orchestrated by Faubus and the segregationists to get exactly the vote they wanted—acceptance of closed schools rather than even token desegregation.

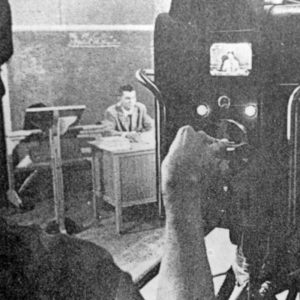

The Lost Year was one of the most peculiar situations in Arkansas history. High school teachers worked in empty classrooms. A private school corporation formed to lease public school buildings and hire public school teachers, but federal courts prevented this. The school district experimented for a few weeks with television teaching by fifteen white teachers on the three commercial television stations. Soon, private schools, aside from the three Catholic parochial schools that already existed, opened to accommodate displaced white students; these included the T. J. Raney School, Baptist High School (which was affiliated with Ouachita Baptist College, now Ouachita Baptist University), and Second Baptist Church. No private schools for black students emerged.

The Lost Year continued with its peculiarities. Within one calendar year, the superintendent and the school board membership changed three times. The Arkansas General Assembly targeted the NAACP (Act 115) and public school teachers (Act 10) with threatening legislation. The latter required teachers and all public employees to sign affidavits listing all organizations to which they belonged and/or paid dues, while the former immediately fired any teacher or state employee who was a member of the NAACP. By May 1959, forty-four teachers and administrators were fired without due process by a rump session of the school board: only three members of the six-member board took the action, declaring themselves a quorum, which was illegal. Though no academic work was conducted in public high schools in 1958–59, high school football games continued for the season by order of the governor.

Perhaps the greatest consequences were the effects on displaced students and their families. Some of the educational alternatives that displaced students found were nearby public schools, in-state public schools where students lived with friends or relatives, out-of-state public and private schools, correspondence courses, parochial schooling, and early entrance into college. Nearby schools such as Jacksonville (Pulaski County) and Mabelvale (Pulaski County) for white students and Wrightsville (Pulaski County) for black students absorbed as many students as they could. Some students, as young as fifteen years old, moved in with relatives in public schools across all of Arkansas, and even out of state. The number of displaced white students was 2,915. Of those, thirty-five percent found public schools to attend in the state. Private schools in Little Rock took forty-four percent of the displaced white students. A total of ninety-three percent of white students found some form of alternative schooling. This was not the case for displaced black students. Among the 750 black students who were displaced, thirty-seven percent found public schools in Arkansas to attend. Some located parochial schooling, out-of-state public and private schooling, and some did enter college early or take correspondence courses. However, fifty percent of displaced black students found no schooling at all. The NAACP, through Roy Wilkins, stated that opening private high schools for displaced black students would defeat their intent to gain equal access for all students to public education. Some of the students from both races went to the military, some went to work, and some married early or simply dropped out. Interviews with many former students indicate lifelong consequences because of this denial of a free public education.

Throughout the Lost Year, several groups organized either to support closed schools or to open them. Among those who worked tirelessly for the latter cause was a large group of white, upper-class women called the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open our Schools (WEC). They organized voter registration, promoted the election of moderates to the legislature and the school board, and worked with others after the teacher purge. The Capital Citizens Council (CCC) and the Mothers League of Central High supported segregation. The purge of forty-four teachers on May 5, 1959, brought voters from both sides of the spectrum to organize a recall of either segregationists or moderates from the Little Rock School Board. This twenty-day campaign was led by two hastily formed groups: the Committee to Retain Our Segregated Schools (CROSS) and a group called STOP (which stood for “Stop This Outrageous Purge”), which worked with the WEC. The Lost Year ended with a recall of three segregationist members of the Little Rock School Board on May 25, 1959. Voters in Little Rock, after a year of closed public high schools and after the firing of teachers, were finally willing to accept limited desegregation. The federal courts followed on June 18, 1959, when a three-judge federal district court declared unconstitutional Arkansas’s closure of schools and withholding of funds (instituted under Act 4 and Act 5).On June 11, the vacancies on the Little Rock School Board were filled by the Pulaski County Board of Education, and all four secondary schools opened early—on August 12, 1959. Token desegregation continued slowly in Little Rock until federal courts encouraged the use of busing to fully integrate all public schools in the nation. In Little Rock, this went into full force in 1971, a date that coincides with white flight to the suburbs and to private schools that opened to serve that constituency.

For additional information:

Alexander, H. M. The Little Rock Recall Election. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1960.

Bartley, Numan. The Rise of Massive Resistance. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969.

Brewer, Vivion. The Embattled Ladies of Little Rock, 1958–1963: The Struggle to Save Public Education at Central High. Fort Bragg, CA: Lost Coast Press, 1999.

Cope, Graeme. “‘A Mockery for Education’? Little Rock’s Thomas J. Raney High School during the Lost Year, 1958–1959.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 78 (Autumn 2019): 248–273.

———. “‘The Workingest, Fightingest, Band of Patriots in the South’? The Mothers’ League of Central High School during the Lost Year, 1958–1959.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Summer 2013): 139–157.

Elizabeth Huckaby Papers, 1957–1978. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Gordy, Sondra. Finding the Lost Year: What Happened When Little Rock Closed its Public Schools? Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009

———. “Teachers of the Lost Year: Little Rock School District, 1958–59.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1996.

Hubbard, Sandra. The Giants Wore White Gloves. Documentary film. Little Rock: Morning Star Studio, 2004.

———. The Lost Year. Documentary film. Little Rock: Morning Star Studio, 2007.

The Lost Year Project. http://www.thelostyear.com/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

The Rebel, 1959 (Yearbook of T. J. Raney High School). Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System. Online at https://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15728coll3/id/546696/rec/1 (accessed July 11, 2023).

Walthall, J. H. “A Study of Certain Factors of School Closing in 1958 as They Affected the Seniors of the White Comprehensive High Schools in Little Rock, Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1963.

Sondra Gordy

University of Central Arkansas

Central High School

Central High School  Desegregation Protest at Capitol

Desegregation Protest at Capitol  Lost Year Class

Lost Year Class  Lost Year Student

Lost Year Student  Mothers' League of Central High School Flyer

Mothers' League of Central High School Flyer  STOP Rally

STOP Rally  WEC Meeting

WEC Meeting

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.